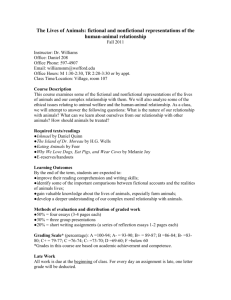

Study Guide - WordPress.com

advertisement