Suggested quotations for writing a body paragraph on prejudice or

advertisement

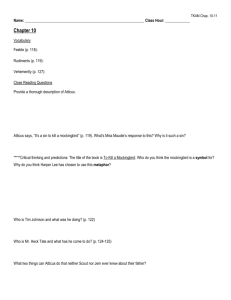

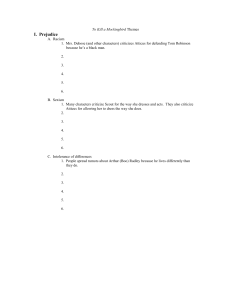

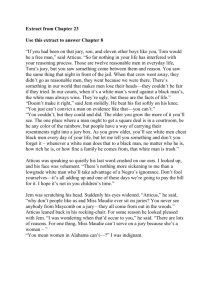

COURAGE When the kids develop a fully mature view of courage as doing what is morally right despite how difficult it is and how much one will personally suffer as a result: Atticus doing the right thing and defending Tom Robinson to the best of his ability even though he knows the town’s many racists will torment his beloved children because of it: “He [Cecil Jacobs] had announced in the schoolyard the day before that Scout Finch’s daddy defended niggers” (74). “If you shouldn’t be defendin’ him, then why are you doin’ it?” “For a number of reasons,” said Atticus. “The main one is, if I didn’t I couldn’t hold up my head in town, I couldn’t represent this county in the legislature, I couldn’t even tell you or Jem not to do something again.” … “Scout … every lawyer gets at least one case in his lifetime that affects him personally. This one’s mine, I guess. You might hear some ugly talk about it at school …” (75-76) “My folks said your daddy was a disgrace an’ that nigger oughta hang from the water-tank!” (76). “I guess it ain’t your fault if Uncle Atticus is a nigger-lover besides, but I’m here to tell you it certainly does mortify the rest of the family—” … “Grandma says it’s bad enough he lets you all run wild, but now he’s turned out a nigger-lover we’ll never be able to walk the streets of Maycomb again. He’s ruinin’ the family, that’s what he’s doin’.” Francis rose and sprinted down the catwalk to the old kitchen. At a safe distance he called, “He’s nothin’ but a nigger-lover!” (83) “Scout’s got to learn to keep her head and learn soon, with what’s in store for her these next few months” (87-88). “What bothers me is that she and Jem will have to absorb some ugly things pretty soon” (88). “Your father’s no better than the niggers and trash he works for!” (102). “Scout,” said Atticus, “when summer comes you’ll have to keep your head about far worse things … it’s not fair for you and Jem, I know that … all I can say is, when you and Jem are grown, maybe you’ll look back on this with some compassion and some feeling that I didn’t let you down. This case, Tom Robinson’s case, is something that goes to the essence of a man’s conscience— Scout, I couldn’t go to church and worship God if I didn’t try to help that man.” (104) Boo Radley saving Jem and Scout from Bob Ewell when Bob Ewell was trying to murder Jem and Scout, risking his life and his cherished privacy to do so: I ran in the direction of Jem’s scream and sank into a flabby male stomach. Its owner said, “Uff!” and tried to catch my arms, but they were tightly pinioned. His stomach was soft but his arms were like steel. He slowly squeezed the breath out of me. I could not move. Suddenly he was jerked backwards and flung on the ground, almost carrying me with him. (262) Then all of a sudden somethin’ grabbed me an’ mashed my costume … I think I ducked on the ground … heard a tusslin’ under the tree sort of … they were bammin’ against the trunk, sounded like. Jem found me and started pullin’ me toward the road. Some—Mr. Ewell yanked him down, I reckon. They tussled some more and then there was this funny noise—Jem hollered … (269-270) I never heard tell that it’s against the law for a citizen to do his utmost to prevent a crime from being committed, which is exactly what he did, but maybe you’ll say it’s my duty to tell the town all about it and not hush it up. Know what’d happen then? All the ladies in Maycomb includin’ my wife’d be knocking on his door bringing angel food cakes. To my way of thinkin’, Mr. Finch, taking the one man who’s done you and this town a great service an’ draggin’ him with his shy ways into the limelight—to me, that’s a sin… If it was any other man it’d be different. But not this man … (276) PREJUDICE The kids and most of the town prejudging Boo Radley based on rumors and gossip, and Scout learning that Boo is not in fact a monster (as rumored) but is a heroic and good person: Jem gave a reasonable description of Boo: Boo was about six-and-a-half feet tall, judging from his tracks; he dined on raw squirrels and any cats he could catch, that’s why his hands were bloodstained—if you ate an animal raw, you could never wash the blood off. There was a long jagged scar that ran across his face; what teeth he had were yellow and rotten; his eyes popped, and he drooled most of the time. (13) “I remember Arthur Radley when he was a boy. He always spoke nicely to me, no matter what folks said he did. Spoke as nicely as he knew how” (45-46). He was still leaning against the wall. He had been leaning against the wall when I came into the room, his arms folded across his chest. As I pointed he brought his arms down and pressed the palms of his hands against the wall. They were white hands, sickly white hands that had never seen the sun, so white they stood out garishly against the dull cream wall in the dim light of Jem’s room. I looked from his hands to his sand-stained khaki pants; my eyes traveled up his thin frame to his torn denim shirt. His face was as white as his hands, but for a shadow on his jutting chin. His cheeks were thin to hollowness; his mouth was wide; there were shallow, almost delicate indentations at his temples, and his gray eyes were so colorless I thought he was blind. His hair was dead and thin, almost feathery on top of his head. When I pointed to him his palms slipped slightly, leaving greasy sweat streaks on the wall, and he hooked his thumbs in his belt. A strange small spasm shook him, as if he heard fingernails scrape slate, but as I gazed at him in wonder the tension slowly drained from his face. His lips parted into a timid smile, and our neighbor’s image blurred with my sudden tears. “Hey, Boo,” I said. (270) “Will you take me home?” He almost whispered it, in the voice of a child afraid of the dark. I put my foot on the top step and stopped. I would lead him through our house, but I would never lead him home. “Mr. Arthur, bend your arm down here, like that. That’s right, sir.” I slipped my hand into the crook of his arm. He had to stoop a little to accommodate me, but if Miss Stephanie Crawford was watching from her upstairs window, she would see Arthur Radley escorting me down the sidewalk, as any gentleman would do. (278) “Atticus was right. One time he said you never really know a man until you stand in his shoes and walk around in them. Just standing on the Radley porch was enough” (279). “Yeah, an’ they all thought it was Stoner’s Boy messin’ up their clubhouse an’ throwin’ ink all over it an’ ….” He guided me to the bed and sat me down. He lifted my legs and put me under the cover. “An’ they chased him ‘n’ never could catch him ‘cause they didn’t know what he looked like, an’ Atticus, when they finally saw him, why he hadn’t done any of those things ... Atticus, he was real nice ....” His hands were under my chin, pulling up the cover, tucking it around me. “Most people are, Scout, when you finally see them.” (281) Aunt Alexandra and others prejudging people in Maycomb, especially the Cunninghams, and Calpurnia teaching Scout not to prejudge based on reputation and/or social class: “It was just a nest of those Cunninghams, drunk and disorderly” (158). “But I want to play with Walter, Aunty, why can’t I?” She took off her glasses and stared at me. “I’ll tell you why,” she said. “Because—he—is—trash, that’s why you can’t play with him. I’ll not have you around him, picking up his habits and learning Lord-knows-what. You’re enough of a problem to your father as it is.” (225) … Walter poured syrup on his vegetables and meat with a generous hand. He would probably have poured it into his milk glass had I not asked what the sam hill he was doing. The silver saucer clattered when he replaced the pitcher, and he quickly put his hands in his lap. Then he ducked his head. Atticus shook his head at me again. “But he’s gone and drowned his dinner in syrup,” I protested. “He’s poured it all over—” It was then that Calpurnia requested my presence in the kitchen. … “There’s some folks who don’t eat like us,” she whispered fiercely, “but you ain’t called on to contradict ‘em at the table when they don’t. That boy’s yo’ comp’ny and if he wants to eat up the table cloth you let him, you hear?” “He ain’t company, Cal, he’s just a Cunningham—” “Hush your mouth! Don’t matter who they are, anybody sets foot in this house’s yo’ comp’ny, and don’t you let me catch you remarkin’ on their ways like you was so high and mighty! Yo’ folks might be better’n the Cunninghams but it don’t count for nothin’ the way you’re disgracin’ ‘em—if you can’t act fit to eat at the table you can just set here and eat in the kitchen!” (24-25) People in Maycomb being racist, and certain more progressive adults (like Calpurnia, Atticus, Miss Maudie, Dolphus Raymond, Judge Taylor, etc.) teaching the kids not to prejudge based on race, and the kids learning about the devastating impact of systemic, institutional racism from the Tom Robinson trial and its clearly blatantly unfair and unjust verdict: “He [Cecil Jacobs] had announced in the schoolyard the day before that Scout Finch’s daddy defended niggers” (74). “‘Do you defend niggers, Atticus?’ I asked him that evening. ‘Of course I do. Don’t say nigger, Scout. That’s common.’ ‘‘s what everybody at school says.’ ‘From now on it’ll be everybody less one—’” (75). “My folks said your daddy was a disgrace an’ that nigger oughta hang from the water-tank!” (76). “I guess it ain’t your fault if Uncle Atticus is a nigger-lover besides, but I’m here to tell you it certainly does mortify the rest of the family—” … “Grandma says it’s bad enough he lets you all run wild, but now he’s turned out a nigger-lover we’ll never be able to walk the streets of Maycomb again. He’s ruinin’ the family, that’s what he’s doin’.” Francis rose and sprinted down the catwalk to the old kitchen. At a safe distance he called, “He’s nothin’ but a nigger-lover!” (83) “Your father’s no better than the niggers and trash he works for!” (102). “Scout,” said Atticus, “nigger-lover is just one of those terms that don’t mean anything—like snot-nose. It’s hard to explain—ignorant, trashy people use it when they think somebody’s favoring Negroes over and above themselves. It’s slipped into usage with some people like ourselves, when they want a common, ugly term to label somebody.” (108) … “What you want, Lula?” she asked, in tones I had never heard her use. She spoke quietly, contemptuously. “I wants to know why you bringin’ white chillun to nigger church.” “They’s my comp’ny,” said Calpurnia. Again I thought her voice strange: she was talking like the rest of them. “Yeah, an’ I reckon you’s comp’ny at the Finch house durin’ the week.” A murmur ran through the crowd. “Don’t you fret,” Calpurnia whispered to me, but the roses on her hat trembled indignantly. When Lula came up the pathway toward us Calpurnia said, “Stop right there, nigger.” Lula stopped, but she said, “You ain’t got no business bringin’ white chillun here—they got their church, we got our’n. It is our church, ain’t it, Miss Cal?” Calpurnia said, “It’s the same God, ain’t it?” Jem said, “Let’s go home, Cal, they don’t want us here—” I agreed: they did not want us here. I sensed, rather than saw, that we were being advanced upon. They seemed to be drawing closer to us, but when I looked up at Calpurnia there was amusement in her eyes. When I looked down the pathway again, Lula was gone. In her place was a solid mass of colored people. One of them stepped from the crowd. It was Zeebo, the garbage collector. “Mister Jem,” he said, “we’re mighty glad to have you all here. Don’t pay no ‘tention to Lula, she’s contentious because Reverend Sykes threatened to church her. She’s a troublemaker from way back, got fancy ideas an’ haughty ways— we’re mighty glad to have you all.” (119) “‘Lemme tell you somethin’ now, Billy’ a third said, ‘you know the court appointed him to defend this nigger.’ ‘Yeah, but Atticus aims to defend him. That’s what I don’t like about it’” (163). “I knowed who it was, all right, lived down yonder in that nigger-nest, passed the house every day. Jedge, I’ve asked this county for fifteen years to clean out that nest down yonder, they’re dangerous to live around ‘sides devaluin’ my property—” (175). He [Tom Robinson] looked oddly off balance, but it was not from the way he was standing. His left arm was fully twelve inches shorter than his right, and hung dead at his side. It ended in a small shriveled hand, and from as far away as the balcony I could see that it was no use to him. “Scout,” breathed Jem. “Scout, look! Reverend, he’s crippled!” Reverend Sykes leaned across me and whispered to Jem. “He got it caught in a cotton gin, caught it in Mr. Dolphus Raymond’s cotton gin when he was a boy ... like to bled to death ... tore all the muscles loose from his bones—” Atticus said, “Is this the man who raped you?” “It most certainly is.” Atticus’s next question was one word long. “How?” Mayella was raging. “I don’t know how he done it, but he done it—I said it all happened so fast I—” (186) “Well, Mr. Finch didn’t act that way to Mayella and old man Ewell when he cross-examined them. The way that man called him ‘boy’ all the time an’ sneered at him, an’ looked around at the jury every time he answered—” “Well, Dill, after all he’s just a Negro.” “I don’t care one speck. It ain’t right, somehow it ain’t right to do ‘em that way. Hasn’t anybody got any business talkin’ like that—it just makes me sick.” (199) “Cry about the simple hell people give other people—without even thinking. Cry about the hell white people give colored folks, without even stopping to think that they’re people, too” (201). “‘Atticus says cheatin’ a colored man is ten times worse than cheatin’ a white man,’ I muttered. ‘Says it’s the worst thing you can do’” (201). “She was white, and she tempted a Negro. She did something that in our society is unspeakable: she kissed a black man. Not an old Uncle, but a strong young Negro man. No code mattered to her before she broke it, but it came crashing down on her afterwards. “Her father saw it, and the defendant has testified as to his remarks. What did her father do? We don’t know, but there is circumstantial evidence to indicate that Mayella Ewell was beaten savagely by someone who led almost exclusively with his left. We do know in part what Mr. Ewell did: he did what any God-fearing, persevering, respectable white man would do under the circumstances—he swore out a warrant, no doubt signing it with his left hand, and Tom Robinson now sits before you, having taken the oath with the only good hand he possesses—his right hand. (204) “I shut my eyes. Judge Taylor was polling the jury: ‘Guilty ... guilty ... guilty ... guilty ….’ I peeked at Jem: his hands were white from gripping the balcony rail, and his shoulders jerked as if each ‘guilty’ was a separate stab between them” (211). “Who?” Jem’s voice rose. “Who in this town did one thing to help Tom Robinson, just who?” “His colored friends for one thing, and people like us. People like Judge Taylor. People like Mr. Heck Tate. Stop eating and start thinking, Jem. Did it ever strike you that Judge Taylor naming Atticus to defend that boy was no accident? That Judge Taylor might have had his reasons for naming him?” This was a thought. Court-appointed defenses were usually given to Maxwell Green, Maycomb’s latest addition to the bar, who needed the experience. Maxwell Green should have had Tom Robinson’s case. (215) “In our courts, when it’s a white man’s word against a black man’s, the white man always wins. They’re ugly, but those are the facts of life” (220). … The older you grow the more of it you’ll see. The one place where a man ought to get a square deal is in a courtroom, be he any color of the rainbow, but people have a way of carrying their resentments right into a jury box. As you grow older, you’ll see white men cheat black men every day of your life, but let me tell you something and don’t you forget it—whenever a white man does that to a black man, no matter who he is, how rich he is, or how fine a family he comes from, that white man is trash. (220) “Tom’s dead.” Aunt Alexandra put her hands to her mouth. “They shot him,” said Atticus. “He was running. It was during their exercise period. They said he just broke into a blind raving charge at the fence and started climbing over. Right in front of them—” “Didn’t they try to stop him? Didn’t they give him any warning?” Aunt Alexandra’s voice shook. “Oh yes, the guards called to him to stop. They fired a few shots in the air, then to kill. They got him just as he went over the fence. They said if he’d had two good arms he’d have made it, he was moving that fast. Seventeen bullet holes in him. They didn’t have to shoot him that much. Cal, I want you to come out with me and help me tell Helen.” “Yes sir,” she murmured, fumbling at her apron. Miss Maudie went to Calpurnia and untied it. “This is the last straw, Atticus,” Aunt Alexandra said. “Depends on how you look at it,” he said. “What was one Negro, more or less, among two hundred of ‘em? He wasn’t Tom to them, he was an escaping prisoner.” (235) … “Have you ever thought of it this way, Alexandra? Whether Maycomb knows it or not, we’re paying the highest tribute we can pay a man. We trust him to do right. It’s that simple.” “Who?” Aunt Alexandra never knew she was echoing her twelve-year-old nephew. “The handful of people in this town who say that fair play is not marked White Only; the handful of people who say a fair trial is for everybody, not just us; the handful of people with enough humility to think, when they look at a Negro, there but for the Lord’s kindness am I.” Miss Maudie’s old crispness was returning: “The handful of people in this town with background, that’s who they are.” (236) “Atticus had used every tool available to free men to save Tom Robinson, but in the secret courts of men’s hearts Atticus had no case. Tom was a dead man the minute Mayella Ewell opened her mouth and screamed” (241).