South African Footballers in Britain research paper

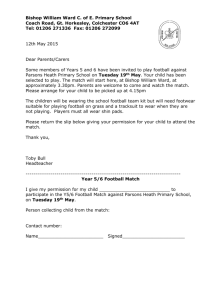

advertisement