Poetry, Pedagogy, and Popular Music: Renegade Reflections

advertisement

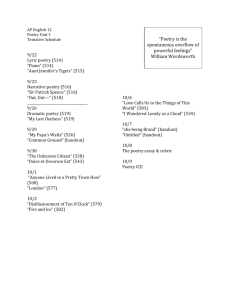

Poetry, Pedagogy, and Popular Music: Renegade Reflections (1999) It's been more than a quarter of a century since I published Beowulf to Beatles: Approaches to Poetry (1972), and two decades since I put together A Generation in Motion (1979), The Poetry of Rock (1981), and Beowulf to Beatles and Beyond (1981). A long, strange trip it's been, and you'd probably not believe me if I told you all I've learned. The major development in my academic home, Department of English, has been the deconstruction of the traditional Canon of British and American Authors and its reconstruction into a house of many mansions based mainly on historically marginalized races, genders, and sexual preferences. This deconstruction is now embodied in many curricula and most textbooks, most notoriously in The Heath Anthology of American Literature (1991). As Lillian Robinson correctly noted in reviewing the Heath for The Nation (July 2, 1990), the book "recognized gender, race and ethnicity as literary categories." Many Old Ones suspect it made race, class, and ethnicity the primary literary categories, and Jack Vincent Barbera (College English, September 1991) found Helen Vendler's position in The Music of What Happens "valuable because it runs counter to the frequently advanced view that a canon is purely [italics his] the product of ideology—be it nationalistic, sociological, racial, economic, sexual, literary, pedagogics and so on" (588). I once disapprovingly described this reconstruction in a paper (presented far from my politically correct Minnesota home) as "Junkbonding the Canon." My reservations included the following: A fourth criticism is that the anthology has not become diverse enough. Where are the writers of science fiction, mystery, horror, adventure, pornography, sports, ecology, and (demands one critic) Harlequin romances? The writing of Jewish-Americans is significantly underrepresented. Polish-Americans do not exist. The Norwegian-American world of Ole Rolvaag, the Irish-American world of James T. Farrell, the Armenian-American world of Bill Saroyan, the Greek-American world of Harry Petrakis, the Czech-American world of Norb Blei—this list could go on for some while—do not appear in this version of the canon. And if the orally transmitted texts of Native Americans and Blacks are to be part of the new canon, why not the orally transmitted writings of Garrison Keillor or other prominent radio and television commentators? Why not film scripts? Why not the songs of Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Jim Morrison, the Legendary Woody, or, carry the argument to its logical conclusion, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stroller, whose "Yakety Yak" is more familiar to more Americans than any single work by any single writer in the entire Heath Anthology? (101) The heated discussion following my presentation was highlighted by accusations from an American who knew my work that Beowulf to Beatles was a significant deconstructionist text and I, too, was a junk bonder. He was, coincidentally, a contributing editor to the Heath Anthology. But Beowulf to Beatles, and other rock poetry texts like Homer Hogan's Poetry of Relevance (1970) and David Morse's Grandfather Rock (1972), were not deconstructionist in the spirit of those who created the Heath and shaped the present English Department. First, the rock poetry texts represented an expansion by genre, not by race, class, and gender. Similar lateral expansions of the early seventies took English profs into film, science fiction, detective fiction, and even erotica. In the eighties most English departments ceded much of American popular culture to departments of American Studies. Vestiges remain, though, in Modern Language Association panels on cinema, science fiction, and detective fiction. Second, the idea behind treating rock songs as a legitimate form of poetry was not so much to make poetry "relevant" as to make poetry "familiar." Rock was a familiar form of poetry, and thus accessible, and thus a useful starting point for excursions into the genre. Deconstructionists have favored either postmodern poets or the poetry of cultural diversity, material unfamiliar to most students. Thus the Heath and other anthologies have managed to remove poetry even further from the real life of college students than it was in, say, 1970. Third, the rock texts did not present an argument based on race, class, and gender . . . did not even recognize race, class, and gender as literary categories. Quality—or the construct of quality—remained a significant consideration, perhaps the main literary measuring stick. Even purely rock anthologies like Stephanie Spinner's Rock Is Beautiful (1970), A. X. Nicholas's The Poetry of Soul (1971) and Richard Goldstein's The Poetry of Rock (1969) agreed. On page 3 of The Poetry of Rock, Goldstein wrote, "Today, it is possible to suggest without risking defenestration that some of the best poetry of our time may well be contained within those slurred [rock-n-roll] couplets." I expressed the hope that qualitative judgments formed in literary criticism could be brought to bear on pop music, where I thought discrimination was sorely needed. On page 3 of Beowulf to Beatles, I wrote, "If there is one thing America needs, it is a little taste." Nor were rock poetry textbooks of the early seventies hostile to canonical writers, as the Heath crowd clearly was. We saw the Old Ones as the main show, a criterion of excellence to be matched and a tradition to be preserved. For Homer Hogan, rock was a bridge from the familiar into canonical poetry. In his preface he wrote, "Poetry of Relevance invites students to find significant connections between poems of our literary heritage and songs that express contemporary interests and concerns" (iii). I wrote, "Those who are unwilling to accept the idea of poetry of rock may still find it useful to use rock as a vehicle into more traditional material, which is also contained in this volume" (xxvi). I ended my preface with the sincere hope that Beowulf might do something to mitigate "the current American distaste for poetry of all kinds" (xxix). Even Goldstein, whose book contained only rock lyrics, bowed to traditional poetry: "To claim that he [Dylan] is the major poet of his generation is not to relegate written verse to the graveyard of cultural irrelevance. Most young people are aware of linear poetry" (6). Not anymore. Modern American Literature classes teach more poetry than ever, and anthologies are bloated with gender and ethnicity poetry (little emphasis on class) not including, alas, the songs of Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Jim Morrison, or the Legendary Woody. These books are thick and expensive. The classes in which they are taught are smaller than those I remember in the seventies, when a section of Modern American Literature contained maybe one-third literature majors and two-thirds business, psychology, biology, and even speech and hearing science majors. Poetry, in fact, has fallen upon beat and evil times. I know the poetry situation in America too well. In another incarnation, I am publisher-editor-typesetter-shipping clerk of Spoon River Poetry Press, which since 1978 has published between two and six books of poetry a year, saddle-stapled chapbooks to 460page hardbacks. From 1976 to 1986 I edited the Spoon River Quarterly, (now Spoon River Review), a journal devoted exclusively to poetry. On the production side, modern poetry is kinetic as a beaver in spring: writing classes, small press publishers, reading series and festivals, visiting writers, criticism in scholarly journals. After a year at the University of Iowa, Swiss poet Robert Rehder reported: My impressions of contemporary American poetry after a year in the United States are of intense activity and intense struggle: thousands of poets writing thousands of poems, a fraction of which are published by hundreds of little magazines and small presses, without anyone having any comprehensive or clear vision of what is happening, but everyone pushing all the time to have a place in the sun—an unending big city rush hour. Teaching creative writing is a growth industry and very much part of the smash and grab of American academic life. Many poets are desperately competing for money, jobs, fellowships, prizes, and the fifteen minutes of fame that Andy Warhol promised us all. . . . They were doing this, however, with virtually no sense of nationality—the Americanness of the work was of no particular concern—but with, perhaps, a strong unconscious sense of cultural solidarity. (111) On the marketing side, poetry is a disaster. Everyone inside the English Department claims to read contemporary poetry, and Rehder reports "an obsession with the contemporary and the new, especially among the workshop students" (I 12). However, few academics actually buy books of poetry. (It was Kenneth Patchen who once observed that people who claim to love poetry and don't buy poetry books are a bunch of cheap sons-of-bitches.) Martin Arnold, in "Finding a Place for Poets," notes that in 1998 sales of all Knopf poetry titles, including 30 volumes in the Everyman Pocket Poetry Series, were a quarter of a million books (B3) in this nation of 200 million adults, 50 million of whom hold college degrees, 15 million of whom hold advanced college degrees. Deborah Garrison's A Working Girl Can't Win (Random House, 1998) sold 20,000 copies, but that was due to "a built-in demographic—the young working professional and her plights and her life" (Arnold B3). For most books of poetry 1,000 sales units is an acceptable, 10,000 units an "excellent, ego-building," and 20,000 units a "newsworthy" (Arnold B3) figure. Few major publishers will take on a collection of poetry which has not won a major prize, and many university and small presses underwrite poetry books with foundation grants and entry fees for contests which select, from 500 or 1,000 manuscripts, a single winner, often a chum or protege of the judge. Most reviewers ignore poetry, except collections of local interest. They might as well: books would be unavailable in the local chain bookstore, where the "poetry section" is a single shelf containing maybe a dozen books by living authors. Paul Zimmer, former editor of the prestigious Pitt Poetry Series, told me a decade ago that the aggregate sales of all titles in the Pitt Poe" Series was substantially below the number of people who would watch the Cincinnati Reds play baseball on a single September weekend. Authorlink!, a website which has been relatively successful in connecting authors and agents, achieves its 65% rate by avoiding poetry entirely: "Poetry is not accepted at this time," the gatekeeper warns. "Have you noticed the paucity of poetry in American public life?" William Safire asked in a recent number of the New York Times Magazine (28). "The Poetic Allusion Watch (PAW), once an annual event in this space, has been shut out for lack of examples." Martin Arnold opens his New York Times essay on "Finding a Place for Poets" with a poetic allusion . . . to the poetry of Peter, Paul and Mary: "Where have all the poets gone, long time passing; where have all the poets gone, long time ago?" (B3). In contrast, the music situation has for years been in growth mode on both production and consumption sides. Songs are everywhere: on radio, in office and car, in commercials on television, in school hallways, at sporting events, on airline headsets. (Try finding the poetry channel on your next transatlantic flight; try finding a television commercial that incorporates a post-World War II poem.) Old 45s, albums, cassettes, and CDs fill flea markets and antique shops. (Ever see a volume of postmodern poems at a garage sale? When last did anyone outside the English Department bootleg a postmodern poem?) My students, of course, come turned on, plugged in. They are all the time recommending a new CD by Natalie Merchant, Dead Can Dance, Ani DiFranco, Indigo Girls, or Hootie and the Blowfish to drag their graybeard prof out of the sixties and into the nineties. 10,000 units is more like the number of promotional freebies passed out by major recording companies. And no matter how music forms proliferate, people seem to keep track of them all. Rockers like Jim Morrison, John Lennon, Joni Mitchell, and Bob Dylan even sell books of prose and poetry. Songwriter Jewel received a seven-figure advance from HarperCollins for A Night without Armor (Arnold B3). Even among writer and English professor friends, I have noticed that the lingua franca, the corpus of allusions to which a listener can be expected to respond, is more film and pop music than literature. We do whole dialogues from films, and carry on conversations in lines from songs. Almost never do we trade lines from a contemporary poet. So just how desperate is the contemporary poetry situation? It was after exchanging five minutes of The Blues Brothers dialogue with friends at the University of Toledo recently that I conceived a project to assess the relative positions of music and poetry in modem American life. It was a three-part questionnaire—nothing scientific, just a bit of fun to verify a reality that we all know exists. In part one I listed thirty winners of the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry from 1950 to 1995, and asked respondents if they could (a) name a poem or (b) quote a line from a poem by W. D. Snodgrass, Alan Dugan, Louis Simpson, John Berryman, Richard Eberhart, Anne Sexton, Anthony Hecht, George Oppen, Richard Howard, William S. Merwin, James Wright, Maxine Kumin, Gary Snyder, John Ashbery, James Merrill, Howard Nemerov, Robert Warren, Donald Justice, James Schuyler, Sylvia Plath, Galway Kinnell, Mary Oliver, Carolyn Kizer, Henry Taylor, Rita Dove, William Meredith, Richard Wilbur, Charles Simic, Mona Van Duyn, or Yusef Komunyakaa. In part two I listed thirty major singers and groups from the fifties through the early nineties and asked for a song title or line from the Beatles, Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Glen Campbell, Frank Sinatra, Paul Simon, Carole King, Stevie Wonder, CCR, the Rolling Stones, Mariah Carey, the Doobie Brothers, Michael Jackson, Tina Turner, Elton John, Billy Joel, Whitney Houston, Hootie and the Blowfish, Phil Collins, U2, Sting, George Michael, Bonnie Raitt, Prince, Madonna, Janet Jackson, the Beach Boys, Aretha Franklin, John Mellencamp, and Garth Brooks. Then things got interesting. In the third part, I gave respondents lines from 25 hit songs and 25 major poems of the post-World War II period, and asked them for the line following the line I gave them. "Take out the papers and the trash…." "Huffy Henry hid the day…." “Yesterday all my troubles seemed so far away…." "As I said to my/friend…." "I have climbed the highest mountain, I have run through the fields…." "It's the end of the world as we know it…." The songs were student recommendations; the poems were nominated by English Department colleagues. There was nothing scientific in the construction of the "test instrument," and very little scientific about the test administration. My only real problems were finding 25 post-World War II poems commonly held to be significant, while cutting back to a mere 25 songs. I distributed the Test Instrument to friends, colleagues, and students; to a few high school teachers, who passed it along to their students; and, at a Thanksgiving gathering, to members of my family. The results were what I expected in a country where rock music is ubiquitous and post-World War II poetry is virtually invisible. Among 65 people responding, results were as follow: 39 very loosely defined identifications of a title or line from the 30 post-World War II Pulitzer Prize winning poets; 1,444 titles or identified lines from the 30 post-World War II singers and groups. I got a total of 14 responses to my request for the second line of a poem, and a total of 611 second lines of songs. Among college student responses, a total of 692 song titles or song lines, and 298 second lines to my first line; a total of four responses to the Pulitzer Prize-winning poets, including two second lines (the winners were Gwendolyn Brooks's "We Real Cool" and Allen Ginsberg's "Howl") and two poem titles, if you count "something about a bouncing ball" and "I heard of her [Sylvia Plath]." Twenty-one college students could quote the second line of Leiber and Stoller's "Yakety-Yak"—five times as many as responded in any way to all postWorld War II Pulitzer Prize winners, in or out of the Heath Anthology. Fifty percent of the college students could name a song or quote a line by the Beatles, Mariah Carey, Michael Jackson, Elton John, Billy Joel, Whitney Houston, Garth Brooks, Madonna, and the Beach Boys. The college kids also scored a 25% or better recognition on Elton John, Hootie and the Blowfish, Phil Collins, George Michael, Prince, Janet Jackson, CCR, the Rolling Stones, Tina Turner, John Mellencamp, and, surprisingly, on Bob Dylan, Aretha Franklin, and Frank Sinatra. With half as many responses, high school results replicated college results: one recognition of a poet and one second line of a poem (again, Gwendolyn Brooks), widespread recognition of the Beatles, Mariah Carey, Michael Jackson, Tina Turner, Elton John, Madonna, the Beach Boys, and recognition, even among high school students, of Frank Sinatra, Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, and Aretha Franklin. Eight of 13 Rutgers Prep School students, ages 14 to 17, could quote the second line of "Yakety-Yak," and two could quote the second line of Bob Dylan's "Rainy Day Women #12 & 35." Ten could complete Madonna's" 'cause we're living in a material world..." and eleven could complete Aretha Franklin's "R E S P E C T…" The English profs, recognizing professional embarrassment when it was about to bite them on the left ear lobe, mostly lost or forgot to return their exams. Many of those which were returned bore selfexculpatory explanations like "Pulitzer Prizes are awarded for a body of work, rather than for one or two significant poems," or "This is what comes from being a medievalist." (My own Ph.D. is in medieval literature.) I heard, "You know, I used to teach these writers when I taught Modern Poetry, but right now I can't think of a single poem by these authors. I'd have done better if you'd have asked about Dave Etter or Bill Kloefkorn [two regionally famous Midwestern poets]." One colleague admitted, "You said, 'don't cheat.' I wouldn't even know how to cheat on some of the poets." From one Ph.D. candidate: "Louis Simpson—wasn't he a professional wrestler or something?" From another, "John Berryman: an actor? One of the Chicago 7?" The big surprise among professors of English, however, was their familiarity with the songs: in contrast to 25 titles to or lines from the poets, they wrote down 120 titles to or lines of songs. Seven could answer a line of poetry (Randall Jarrell's "Death of the Ball Turret Gunner," Sharon Olds's "Sex Without Love," Ted Roethke's "I Knew a Woman," Sylvia Plath's "Lady Lazarus," and Gwendolyn Brooks's "We Real Cool"), but 37 responded to my line of a song with the next line. The most amazing return came from a 45-year-old Shakspearean scholar who also publishes poetry: she wrote nine responses to the poets and then nailed 28 of the 30 singers, giving titles and lines for everyone except Stevie Wonder and Hootie and the Blowfish. Among high school teachers and the adult laity, the same sad refrain. Sylvia Plath was known to four, but for her prose autobiography, The Bell Jar. Robert Penn Warren was known to one . . . for his novel, All the King's Men. The Old Ones (ages 30 to 72) were a little light on Garth Brooks, Janet Jackson, U2, Mariah Carey, and Hootie, but they were all over the Beatles, the Stones, Billy Joel, Bob Dylan, Frank Sinatra, Paul Simon, Elton John, the Doors, and—surprise!—Madonna, Michael Jackson, and Pink Floyd. Ten of fifteen remembered the second line of "Yakety Yak." One high school English teacher wrote at the bottom of her questionnaire, "I am so ashamed that I know more songs than poems." She should not be. Clearly, just as film and television fill the need of most Americans for narrative, popular music fills the need of most Americans for poetry. It's that simple. This is bad news for English Departments, given the direction they have taken over the past two decades. The response to my poetry-rock survey of Tara Mischke, one of the smart students who sat in the front row, said it all: "Modem poetry sucks." She voiced the consensus of most students, and of most Americans. They may be right, or they may be wrong, but either way Departments of English are in trouble. As Sandburg put it in "The People Yes,” “Whether the stone bumps the jug or the jug bumps the stone it is bad for the jug." You can lead students to the American literature anthologies, but they don't have to read. Department of English has driven its proverbial ducks to the proverbial wrong pond. We are barking up the wrong free. We have been led down the primrose path. We are headed up the proverbial Shit Creek. English professors need to remind themselves that however exquisite their mansion may look from within, it is but a postmortem construct of dubious social utility. With its self-reflexive complexities of hierarchy, occult ritual, unspoken taboos, and arcane argot, the Modem Language Association is just a street gang with Ph.D's. At 31,000 member (many of them institutional or grad students seeking jobs), the MLA is less numerous than the American Rabbit Breeder's Association (membership 38,000), the National Organization of Women, and the Harley Owner's Group (275,000 each), or the Women's Missionary Union of the Southern Baptist Convention (1,200,000). As Camille Paglia warns, "a serious problem in America is the gap between academia and the mass media, which is our culture. Professors of humanities, with all their leftist fantasies, have little direct knowledge of American life and no impact whatever on public policy" (ix). The distance is unfortunate for both sides, but especially unfortunate for academics in departments whose staffing is determined by the number of FTE (full-time equivalent) student enrollments. With the Department of American Studies right next door, how long can English Departments market "Contemporary American Literature" classes full of sterile postmodern game-players and culturally diverse mediocrities? How long will students elect classes divorced from both the majestic past and their own chaotic present? Cultural history is littered with the bones of dinosaurs who thought they had adapted. Recent cultural history especially reminds us that bad ideas inevitably collapse upon themselves, although not without a terrible price. I saw the Berlin Wall go up, and I have seen the Berlin Wall come down. I spent a total of three years on two different Fulbright assignments in the ruins of the Soviet Union, an experiment in egalitarian doctrines (and institutionally sanctioned correct thought and speech) not unlike those held by many American race and gender theoreticians. Too many English Departments of the 1980s and 1990s resemble in ways spiritual and physical the wreckage of Lodz, Poland, and Riga, Latvia. These are not places a sensible person cares to spend a lot of time. What went wrong with Paul Lauter and the cadre of academic fellow travelers who created the new American Literature canon over the course of several NEH seminars, three academic treatises (Canons and Contexts, Redefining American Literary History, and Reconstructing American Literature), and the Heath Anthology? In his general introduction to the Heath, Lauter speaks of "a cultural heritage" rather than a literary canon. He should have been sympathetic to lateral expansion by genre. He should have been hostile to the split between "high" and "low" culture found in most English Departments and reflected in, for example, Thomas Swiss's discussion of poetry and popular music in Popular Music and Society (18.2): "How does poetry, as a 'high' art, respond to the popular art of rock music?" What became of the singers in the new American Literature anthologies? One possibility is that the reconstructionists were not nearly as hip as they pretended to be. Beneath the black face of a borrowed Other lurked their sorry, bleached, grad-school-credentialed, middle-class, Anglo selves. To quote Paglia again, "The most interesting and daring minds of my generation did not, as a rule, go on to graduate school or succeed in the academic system. Hence our major universities are now stuck with an army of pedestrian, toadying careerists, Fifties types who wave around Sixties banners to conceal their record of ruthless, beaver-like tunneling to the top" (viii). Favorite English Department writers are frequently as beaver like as the faculty teaching the classes . . . and as mediocre, and as removed from American life. "High," or true, culture can be fabricated from elements of popular materials ("the central question of how to mark out a 'high' literary space for a 'popular' musical subject," Swiss 2, italics mine), but popular culture could not itself be real culture. A second possibility is that in English Departments of the 1980s, poetry became the province of MFAs from the Iowa Famous Writers Famous Workshop and its less celebrated clones, who were more interested in quid pro quo deals with other academic writers than with rock superstars who were unlikely to give them the time of day, let alone trade home-and-home readings. The stocks they watched were posted in The Writer's Chronicle and American Poetry Review, not in Rolling Stone, and they charted reputations and invited visiting poets accordingly. A third possible culprit is the aforementioned cadre of Francophile theoreticians (rhymes with morticians) of various ideological persuasions. The older ones spent the sixties stuck inside the nineteenth century with the Sense and Sensibility blues again. The younger ones are perhaps best described by Samantha in Edward Allen's novel Mustang Sally, who tells a fictional MLA session, "The pretty girls go on to get rich husbands—I hope—and the ugly ones go on to get Ph.D.s" (271). The sable cloaks and black Puritan hats of both older and younger inhibited full-tilt intellectual boogie. Another possibility is that English Department profs are so full of social justice, and so offended by anything commercial, that they resist rock and pretend to cultivate printed poetry precisely because one is a commercial success and the other is such a patent commercial failure. Postmodern poetry is even more marginal—and thus presumably more subversive—than popular musicians, many of whom have been canonized in spite of themselves (see Bernard-Donals), especially classic rockers from Elvis to Dylan to Sir Elton John, but even recent flappers like Madonna, rappers like Hammer, and crappers like the Spice Girls. As I write, the underground poetic discovery making Internet rounds is one Joe Salerno, who died in November 1995, after writing poetry for thirty years, winning arts council grants, giving readings, but never stooping so low as to publish a book. The poem I am repeatedly sent is titled "Poetry Is the Art of Not Succeeding." Here is true marginality! Or perhaps academics fear anything popular because it opens the possibility that students will know more about the subject than they. Not without reason do academic tastes in film privilege experimental, pretentious, and usually low-quality art films that few have ever heard of and even fewer have survived without falling asleep. Or perhaps the reason Bob Dylan and Paul Simon lyrics do not appear in the anthologies of Contemporary American Literature is far less sinister, a matter of permissions costs. What has always blocked the comprehensive anthology of rock lyrics is, simply, money. Whatever brought us to the present debacle, English Departments need to reassess their commitment to obscure modern printed poets. They need to bridge, not exacerbate, the split between literary and popular culture, working along critical and intellectual lines suggested by Jon Solomon in his essay "Sting in the Tradition of the Lyric Poet." We need less attention to David Wojahn's postmodern rock-n-roll sonnets, Michael Harper's Dear John Coltrane, and the minor-leaguers anthologized in Jim Elledge's Sweet Nothings: An Anthology of Rock and Roll in American Poetry. We need lots more attention to the rock-nrollers themselves. Such a reassessment might in the long run prove beneficial, since large classes are more satisfying than small classes, and continued employment is better than unemployment. Paul Simon and Bob Dylan (and Madonna and Sting) will do far more to mitigate "the current American distaste for poetry of all kinds" than Adrienne Rich, Audre Lorde, Michael Harper, Cathy Song, and Rita Dove. Reassessment need not be painful or even revolutionary. As Jon Solomon notes, "Traditional literary history would re-categorize Sting under the genre of lyric poet, and examining Sting and his 'music' as part of this very tradition can in fact put Sting (and his contemporaries) into a useful and tantalizing historical perspective" (33). Rock is not always alien territory: rock is as allusive to traditional literature as new poetry seems allusive to, or built upon, pop music (see especially Solomon and Duxbury). Nor need introducing rock poets into the English curriculum be painful, since the average English prof seems to know postmodern music better than postmodern poetry. Blues and jazz of the '20s and '30s find their way into English Department classrooms as historical context for the printed works of Zora Neale Hurston, James Weldon Johnson, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Toni Morrison. The MLA remains committed to film and even, in the 1998 conference, to opera (sessions 369, 446) and architecture (164, 215). It might open its doors a crack to rock poetry. Presenters in 1998 MLA session 133 offered papers on "Billie Holiday: Dark Lady of the Sonnets" and "Hart Crane's Swinging Muse." Maybe for the millennium MLA conference, instead of poets like Denise Levertov, Charles Wright, John Clare, George Oppen, Richard Stem, Czeslaw Milosz, Adrienne Rich, and Robert Duncan, who read in 1998, the Association could invite Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Michelle Shocked, Natalie Merchant, Ani DiFranco, lce-T, Joni Mitchell, and Dead Can Dance. Then MLA could offer sessions on the work of each. Ironically, acknowledgment of rock lyrics as poetic texts would not require retreat on matters of gender (see Becker), cultural diversity (see Deanna Robinson), or class (see van Etteren). From Chuck Berry to Madonna to Ice Cube, popular music has been as culturally diverse as printed literature, and far more daring and succinct on class and sex than anything in the English anthologies. "The attitudes, values, and beliefs expressed in modem tunes depict the major concerns of our time," wrote B. Lee Cooper in Images of American Society in Popular Music (xiv); personal identity, ecology, freedom, militarism, political protest, women's liberation, and so on. In short, the lyrics of popular songs are valuable tools for accomplishing the twin educational goals of self-evaluation and social analysis." Things have not changed in the past fifteen years. Compare Madonna's "Justify My Love" and Adrienne Rich's "Twenty-One Love Poems"; Sting's "They Dance Alone" and Carolyn Forche's "The Colonel"; Bruce Springsteen's "The Ghost of Tom Joad" and Tom McGrath's "Long shot O'Leary Counsels Direct Action." The Village People's "YMCA" and Allen Ginsberg's "On Neal's Ashes"; Dylan's "Make You Feel My Love" or the songs on B. Lee Cooper's 43-page list of rock-n-roll love songs (Resource Guide, 138-81), most of which you can sing from memory, and your five favorite postmodern love poems . . . which you probably cannot even name. Late in 1967, Robert Christgau made an ambivalent case for rock as poetry in his oft-quoted essay for Cheetah, "Rock Lyrics are Poetry (Maybe)." In 1972, the case was further argued by myself in Beowulf to Beatles (and later in The Poetry of Rock), by Barbara Graves and Donald McBain in Lyrical Voices: Approaches to the Poetry of Contemporary Song, and by Harold F. Mosher, Jr., in "The Lyrics of American Pop Music: A New Poetry." Three decades later, the case apparently needs capsule restatement. We might survey the long and fruitful cohabitation of poetry and song, from Greek culture to Beowulf to the Beatles This tradition includes poetry of the classical Greek period (see Solomon), epics, border ballads, medieval lyrics, Shakespearean and other Renaissance songs (see Maynard). Then came the divorce wrought by the printed page (poetry into print, music into performance), an underground existence of sung poetry during the 18th and 19th centuries in the form of hymns and art songs (see Kramer), Alexander Graham Bell and the Reunification, with singer-poets like Cohen and Dylan, and experiments from the poetry side: Lindsay, Ferlinghetti, Ginsberg, jazz-poetry fusions, Out Loud Poets, Caedmon and Spoken Arts catalogs of recorded poetry, poetry slams, Laurie Anderson's performance art, Robert Bly, punk/rappoetry collaborations like the New York experiment described by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. (New Yorker, 1985), or the California version described by Dean Kuipers (Playboy, 1994). "Poetry. Rock. They become the same," wrote David Morse in closing his preface to Grandfather Rock (5). We might examine the many and various functions of poetry, noting the curiously similar roles of poets and singers. The poet as cultural historian, as in Homer's Iliad, Allen Ginsberg's "Howl," the Legendary Woody's "Pretty Boy Floyd," or Billy Joel's "We Didn't Start the Fire." The poet as entertainer: T. S. Eliot reading in his wry banker's voice "Macavity: The Mystery Cat," Vachel Lindsay performing "The Congo," Michael Jackson chanting "Beat it, Beat it.” "The poet as social conscience: Percy Shelley in "Sonnet: England in 1819," Robert Bly in "The Teeth Mother, Naked at Last," Bob Dylan in "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll." The poet as visionary: Stephen Spender's "I Think Continually of Those Who Were Truly Great," John Lennon's "Imagine." The topical poet commemorating small moments of not-sosmall significance, including deaths (A. E. Housman's "To an Athlete Dying Young" and Frank O'Hara's "The Day Lady Died," Elton John's "Candle in the Wind" and U2's "Pride [In the Name of Love]") and public events from political conventions to rock festivals (Allen Ginsberg's "Going to Chicago," Joni Mitchell's "Woodstock"). The poet as archetypal myth maker, like Galway Kinnell in "The Bear" and Madonna in "Justify My Love," "Open Your Heart," "Like a Virgin," "Material Girl." The poet as social critic, like Sylvia Plath in "Lady Lazarus" and Ice Cube in "What Can I Do?" The poet as philosopher, like William Butler Yeats in "A Dialogue of Self and Soul," and Kerry Livgren in "Dust in the Wind." The poet as an artist-seer, seeking to expand the range of verbal expression. Like Whitman and William Carlos Williams and Gertrude Stein in their day, and Lennon-McCartney, Bob Dylan, and Ice Cube in ours. We might observe the forms of poetry: ballads, like Ezra Pound's "Ballad of the Goodly Fere" and Gordon Lightfoot's "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald." Love complaints, like Wyatt's "Farewell Love" and Felice and Boudleaux Bryant's "Bye Bye, Love." Rhymed couplets, like Pope's "Essay on Man" or Leiber-Stoller's "Yakety-Yak." Free verse or prose poems like "Song of Myself" or "Unchained Melody." Poems come in quatrains, like Dickinson's "Because I Could Not Stop for Death"—and "Oh, God, Our Help in Ages Past" or "The Yellow Rose of Texas" or the A melody of "Teen Angel," to which tunes most Dickinson poems can easily be sung. There are imagistic poems, like William Carlos Williams's "Red Wheelbarrow" and that remarkable B section of "Unchained Melody." There are experimental collages of words and phrases, like Charles Olson's Maximus poems and the Beatles' "Revolution 9. Many poets rely on alliteration: "Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches' wings" or "with your mercury mouth in the missionary times. . . .” Other poets prefer metaphors: "My love is like a red, red rose" or "Like a bridge over troubled water I will lay me down." There is the poetry of wit: Ben Jonson's epigrams, Paul Simon's "Fifty Ways to Leave Your Lover." There is the poetry of plain statement: e. c. cummings's "Plato told" or Jim Croce's "Time in a Bottle." There is poetry that denies poetry: Robert Creeley's "I Know a Man," ReidBrooker's "A Whiter Shade of Pale." Rock songs do virtually everything that traditional, or "Iinear," poetry does—with the possible exception of making a shape on the page. In addition, rock explores aspects of language as sound, including pitch, tempo, and volume, cadence, rising and failing intonation. Rock poets are richer than traditional poets, richer than even those traditional poets gifted with an car for the spoken language (often honed on jazz, blues, hymns, or other forms of music), richer also than traditional poet-performers who publish on tape or CD. (More than anything else, Laurie Anderson proves the need for tune as well as percussion.) The bottom line is that whatever traditional poetry is, rock poetry is also. Chuck Berry, Bob Dylan, Paul Simon, Leonard Cohen, Lennon-McCartney, Billy Joel, Sting, Bruce Springsteen, and possibly even Leiber-Stoller are major postwar poets. With obvious Spice Girl exceptions, pop may at this moment be more professional than printed poetry, and if lessons of quality are to flow one direction or the other, it's going to be rock to poetry. The real question is not whether rock can be used with, in lieu of, or as a vehicle into printed poetry, but whether literary criticism serves the appreciation of song. None of us want to see rock led by English Department theoreticians into a quagmire of jargon and abstraction. But we know that threat is real, since musical and visual texts sustain such analysis quite as well as a printed text. I remember one participant at a U.K. conference entreating the author of a very learned, and thus very convoluted, and thus very irrelevant, essay on Bob Dylan to please, please, please find something else to write about and not asphyxiate rock the way criticism offed poetry. Even criticism that does not suffocate can kill in other ways. Intellectual snobbery elevated the complex and allusive Eliot and Pound while depreciating Housman and Frost. Intellectual snobbery elevates literary poets like Ashbery and Rich over rock poets like Sting and Madonna. Intellectual snobbery can also elevate certain kinds of rock poetry over, for example, silly love songs: Bob Dylan and Paul Simon over Buddy Holly or Smokey Robinson. To a degree both editions of Beowulf to Beatles are guilty of that snobbery. Academics need constantly to remind themselves that few poems in the English language can match the intensity of that simple medieval quatrain, "Westron wind, when will thou blow? The small rain down can rain. Christ, that my love were in my arms, and I in my bed again." Or, more recently, of "Lonely river flows to the sea, to the sea, to the open arms of the sea …." An entirely unrelated problem is text: words, music, and even video. As the now-common practice of including printed lyrics in CD cases suggests, rock songs need printed texts. Not even Norton could afford a definitive collection of American rock-n-roll poetry, although a good rock poetry anthology would put the Heath, and the Norton, and even Al Poulin's marvelous Contemporary American Poetry right out of business. It isn't going to happen. We all know the solution, which I cannot recommend here, and photocopy is exactly what people do in gathering the words of various rock poets. CDs are taped; videos are copied. The process is far more laborious than having the bookstore stock 35 copies of the Heath Anthology, but rewarding in proportion to its difficulty. Not only must teachers find a way to reproduce music and visual images, English Department scholars must extend literary criticism in more oral and even visual directions (see Lorch, who argues, "Properly understood, rock videos are the metaphysical poetry of the twentieth century" [143]). Traditional poetry has come to live too much on a printed page. The language of literary criticism focuses too much on word-as-cognitive-symbol, too little on word-as-sound. David Morse reminds us in his introduction to Grandfather Rock, "All poetry is first sound" (1), and sound cannot never be ignored, even in spoken English, where the proper intonation can make words mean exactly the opposite of what they say. Songs especially need sound. Even those songs in which tune is little more than something to hang a lyric on can use music to elaborate ("All You Need Is Love"), undercut ("She's Leaving Home") or underscore ("Paperback Writer") the meaning of words. Music video, an art form which has just scratched the surface of its enormous potential, adds a visual layer to the musical layer. How can we even discuss "Justify My Love" without reference to the video? In confronting rock poetry, literary criticism must expand into areas where the French theorists are not likely to be of much help. Witness academic feminism's complete inability to comprehend Madonna. Still, we know that medieval songs and lyrics from Shakespeare's plays, intended to be sung and performed both, have survived English Department analysis for centuries. If they can survive, so can rock-‘n-'roll. Criticism which directs a viewer to the art object itself is always helpful: close attention to nuance; structural analysis; genre analysis; working familiarity with the habits of symbol, metaphor, allusion. If English Department citizens would teach the right material, crawl out of their theoretical bags, rejoin the real world, the language and techniques of traditional literary analysis would illuminate the dominant American culture and thus help everyone better understand who and what we are. In sum, there is no reason for the Department of American Studies to be hip, while Departments of English are lost in a fog of deconstructionist theory. If American Studies can claim Dylan and Motown, Madonna and rap, so can English. MLA members can become useful and productive members of society. I'd say go for it. Because at the moment, Department of English is missing the proverbial boat. Works Cited Allen, Edward. Mustang Sally. New York: Norton: 1992. Arnold, Martin. "Finding a Place for Poets, Perhaps Not for the Giants." New York Times 14 Jan. 1999: B3. Barbera, JackVincent. "Questions of Canon: Modern Poetry." College English 53.5 (1991):587-98 Becker, Audrey. "New Lyrics by Women: A Feminist Alternative.” Journal of Popular Culture 24.1 (1990): 1-22 Bernard-Donals, Michael. "Jazz, Rock 'n' Roll, Rap and Politics." Journal of Popular Culture 28.2 (1994): 127-38. Christgau, Robert. "Rock Lyrics Are Poetry (Maybe)." The Age of Rock. Ed. Jonathan Eisen. New York: Vintage, 1969. 230-43. Cooper, B. Lee. Images of American Society in Popular Music. Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1982. —. A Resource Guide to Themes in Contemporary American Song Lyrics. New York: Greenwood, 1986. Duxbury, Janell. "Shakespeare Meets the Backbeat: Literary Allusions in Rock Music." Popular Music and Society 12.3 (1988): 19-24. Dylan, Bob. Lvrics 1962-1985. New York: Knopf, 1990. Elledge, Jim. Sweet Nothing: An Anthology of Rock and Roll in American Poetry. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1994. Fazio, Brenda Walton. "It's More Than Rock 'n Roll." English Journal March 1983: 41. Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. "Sudden def." New Yorker 19 June 1995: 34-42. Goldstein. Richard. The Poetry of Rock. New York: Bantam, 1969. Graves, Barbara Farris. and Donald J. McBain, eds. Lyrical Voices: Approaches to the Poetry of Contemporary Song. New York: Wiley, 1972. Hogan, Honier. Poetry of Relevance. Vol. 1 and 2. London: Methuen, 1970. Jaszczak, Sandra, ed. Encyclopedia of Associations. Detroit: Gale Research, 1997. Kramer, Lawrence. Music and Poetry: The Nineteenth Century and After. Berkeley: U of California P, 1984. Kuipers, Dean. "Rock and Roll Meets the Spoken Word."Playboy Feb. 1994: 21. Lauter, Paul, ed. Canons and Contexts. New York: Oxford, 1991. —. The Heath Anthology of American Literature. 2 vols. Lexington, MA: Heath, 1991. —. Reconstructiong American Literature Courses. Old Westbury, NY: Feminist Press, 1983. Lorch, Sue. "Metaphor, Metaphysics, and MTV." Journal of Popular Culture 22.3 (1988): 143-55. Maynard, Winifred. Elizabethan Lyric Poetry and Its Music. New York: Oxford, 1986. Morse, David. Grandfather Rock: the New Poetry and the Old. New York: Delacorte. 1972. Mosher, Harold F., Jr. "The Lyrics of American Pop Music: A New Poetry." Popular Music and Society 1 (1972): 167-76. Nicholas, A. X., ed. The Poetry of Soul. New York: Bantam, 197 1. Paglia, Camille. Sex, Art and American Culture. New York: Random House/Vintage, 1992. Parker, Hershel. "The Price of Diversity: An Ambivalent Minority Report on the American Literary Canon." College of Literature 18.3 (Oct. 1991): 15-30. Pichaske, David R. Beowulf to Beatles. New York: Free, 1972. —. Beowulf to Beatles. New York: Macmillan. 1982. —. "Freshman Comp: What Is This Shit? College English 38.2 (Oct. 1976): 117-24. —. A Generation in Motion. New York: Schirmer, 1979. —. "Junkbonding the Canon." Polish-American Literary Confrontations, Ed. Joanna Durczak and Jerzy Durczak. Lublin, Poland: Maria Curie Skiodowska UP, 1995. 91 -101. —. The Poetry of Rock. Peoria, IL: Ellis, 1982. —. "Toward an Aesthetics of Rock." Illinois English Bulletin 60. 1 (1972): 1-11. Poulin, Al, Jr. Contemporary American Poetry. 5th ed. Boston: Hougliton Mifflin, 1991. "Program of the 1998 Convention." PMLA 11 3. 6 (1998): 1252-462. Rehder, Robert. "Metaphor Is the Name of the Game." Spoon River Review 23.1 (1998): 111-28. Robinson, Lillian S. "I. Too, Am American." Nation 2 July 1990: 22-24. Robinson, Deanna Campbell, Elizabeth Buck, and Marlene Cuthbert. Music at the Margins: Popular Music and Global Cultural Diversity. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1991. Ruloff, A. LaVonne Brown, and Jerry W. Ward, Jr., eds. Redefining American Literary History. New York: MLA, 1990. Safire, William. "Where's the Poetry?" New York Times Magazine 1 Nov. 1998: section 6, 28, 29. Solonion, Jon. "Sting in the Tradition of the Lyric Poet." Popular Music and Society 17.3 (Fall 1993): 3341. Spinner, Stephanie. Rock Is Beautiful: An Anthology of American Lyrics. 1953- 1968. New York: Dell, 1970. Swiss, Thomas. "Representing Rock: Poetry and Popular Music." Popular Music and Society 18.2 (1994): 1-12. Van Elteren, Mel. "Populist Rock in Postmodern Society: John Cougar Mellencamp in Perspective. Journal of Popular Culture 28. 3 (1994): 95-121. Wallenstein, Barry. "Poetry and Jazz." Black American Literature 25.3 (1991): 595-620. Bibliography of Rock Poems and Poets Beatles. The Beatles Illustrated Lyrics. Ed. Alan Aldridge. 2 vols. New York: Delacorte, 1969. —. Things We Said Today: The Complete Lyrics and a Concordance to the Beatles' Songs 1962-1970. Ed. Colin Campbell and Allan Murphy. Ann Arbor, MI: Pierian, 1980. Cohen, Leonard. Stranger Music: Selected Poems & Songs. New York: Random House, 1994. Damsker, Matt, ed. Rock Voices. New York: St. Martin's, 1980. Doors, The. The Complete Illustrated Lyrics. New York: Hyperion, 199 1. Dylan, Bob. Lyrics: 1962-1985. New York: Knopf, 1990. Goldstein, Richard. The Poetry of Rock. New York: Bantam, 1969. Graves, Barbara Farris, and Donald J. McBain, eds. Lyrical Voices: Approaches to the Poetry of Contemporary Song. New York: Wiley, 1972. Hogan, Homer. Poetry of Relevance. Vols. 1 and 2. London: Methuen, 1970. Jewel. A Night Without Armor. New York: HarperCollins, 1998. Mitchell, Joni. The Complete Poems & Lyrics. New York: Crown, 1998. Morrison. Jim. The Lords and the New Creatures: Poems. New York: Simon & Schuster, 197 1. Morse, David. Grandfather Rock: The New Poetry and the Old. New York: Delacorte, 1972. Nicholas, A. X., ed. The Poetry of Soul. New York: Bantam, 197 1. Palmer. Robert. Baby, That Was Rock & Roll: The Legendary Leiber & Stoller. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978. Pichaske. David R. Boewulf to Beatles. New York: Free, 1972. —. Beowulf to Beatles and Beyond. New York: Macmillan, 1982. Reed, Lou. Pass through Fire: The Collected Lyrics.. New York: Hyperion, 1999. Smith, Patti. Patti Smith Complete: Lyrics, Reflections & Notes for the Future. New York: Doubleday. 1998. Spinner, Stephanie. Rock Is Beautiful: An Anthology of American Lyrics. 1953- 1968. New York: Dell, 1970. Springsteen, Bruce. Bruce Springsteen Songs. New York: Avon, 1998. Sting. Sting: The Illustrated Lyrics. Sherman Oaks: IRS Books, 1991. Compact Discography of Rock Poetry Anderson, Laurie. Home of the Brave. Warner 9-25400-2, 1986. —. The Ugly One with the Jewels. Warner. 9045847-2, 1995. Baez, Joan. Diamonds and Rust. A&M, 3233, 1975. The Band. Rock of Ages. Capitol, CDP 793595-2, 1969. The Beach Boys. The Greatest Hits. Capitol, CDP 72438294182, 1970. The Beatles. Abbey Road. Capitol, CDP 7 464462, 1969. —. Magical Mystery Tour. Capitol CDP 7 480622, 1967. —. Revolver. Capitol, CDP'7464412, 1966. —. Rubber Soul. Capitol, CDP 7464402, 1965. —. Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Capitol, CDP 7464422,1967. —. The Beatles (The White Album). Capitol, CDP 7464432, 1968. Benatar, Pat. All Figured Up. Chrysalis/EMI, 7243-831094-2-5, 1994. Berry, Chuck. Golden Hits. Mercury, 826-256-2, 1967. Blondie. The Best of Blondie. Chrysalis, F221337, 198 1. Browne, Jackson. Running on Empty. Elektra/Asylum. 6E 113-2, 1978. Buffalo Springfield. Buffalo Springfield. ATCO, 33200-2.1967. —. Buffalo Springfield Again. ATCO, 33226-2, 1968. Chapin, Harry. The Bottom Line Encore Collection. Bottom Line, 63440-47401- 2, 1998. Chapman, Tracy. Matters of the Heart. Elektra. 61215, 1992. —. New Beginning. Elektra, 61850, 1995. —. Tracy Chapman. Elektra, 60774, 1988. Cohen, Leonard. The Best of Leonard Cohen. Reprise, 46326, 1975. —. More Best of Leonard Cohen. Columbia, 68636,1997. —. Songs from a Room. Columbia, 9767, 1969. —. Songs of Leonard Cohen. Columbia, 9533, 1967. Collins, Judy. Forever. . . The Judy Collins Anthology. Elektra, 62104, 1997. Creedence Clearwater Revival. Creedence Gold. Fantasy, FCD 9418-2. 1973. Croce, Jim. Photographs & Memories. Atlantic, 92570,1975. Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. 4 Way Street. Atlantic, 82408, 1972. Crow, Sheryl. Sheryl Crow. A&M 5 87, 1996. DiFranco, Ani. Little Plastic Castle. Righteous Babe, 12, 1998. —. Living in the Clip. Righteous Babe, 11, 1997. Dire Straits. Brothers in Arms. Warner, 9-25264-2, 1985. The Doors. The Best of the Doors. Elektra, 60345, 1987. —. The Doors. Elektra, 74007. 1967. Dylan, Bob. Biograph. Columbia, 38830,1985. —. Blonde on Blonde Columbia, 841, 1966, —. Blood on the Tracks. Columbia, 33235, 1975. —. Bob Dylan's Greatest Hits, volume 1. Columbia, 9463, 1967. —. Bringing It All Back Home. Columbia, 9128, 1965. —. Highway 61 Revisited. Columbia, 9189, 1965. —. John Wesley Harding. Columbia, 9604, 1968. —. The Times They Are A-Changin'. Columbia, 8905, 1964. —. Time Out of Mind. Columbia, 68556. 1997. The Eagles. Their Greatest Hits. Asylum, EUR 253017, 1976. —. Hotel California. Asylum, EUR 253051, 1976. Eurythmics. Greatest Hits. Arista, ARCD 8680, 199 1. The Everly Brothers. The Very Best of the Everly Brothers. Warner, 1554, 1964. Franklin, Aretha. 30 Greatest Hits. Atlantic, 781668-2, 1985. Guthrie, Woody. Dust Bowl Ballads.. Rounder Records 611040, 1964. —. The Greatest Songs of Woody Guthrie. Vanguard 35, 1972. Holly, Buddy. 20 Greatest Hits. MCA 1484, 1978. Ice Cube. Featuring…Ice Cube. Priority 51037, 1997. Ice-T. Return of the Real.. Rhyme Syndicate 53933, 1996. Indigo Girls. Rites of Passage. Epic EK48865, 1992. —. Strange Fire.. Epic EK 45427, 1986. —. Swamp Ophelia. Epic EK 57621, 1994. Jefferson Airplane. Surrealistic Pillow RCA PCD 1 -3766, 1967. Jewel. Little Pieces of You. Atlantic 82700, 1995. —. A Night Without Armor. Atlantic 51016, 1998. Joel, Billy. Greatest Hits, vols. I and 2. Columbia C2K69391, 1987. Kansas. The Best of Kansas. ABS Associated 2K 39283, 1984. King, Ben E. and the Drifters. Stand By Me. Rhino 81716, 1987. King, Carole. Tapestry. Ode EK 34946, 197 1. The Kinks. The Kinks Kronikles. Reprise 6454, 1971. Lightfoot, Gordon. Gord's Gold. Reprise 2237-2, 1975. Madonna. The Immaculate Collection. Sire Records 26440, 1990. Mellencamp, John. The Best That I Could Do.Mercury 314536738-2. 1977. Merchant, Natalie. Ophelia. Elektra 62196, 1998. —. Tiger Lily. Elektra 61745, 1995. Mitchell, Joni. Hits. Reprise 46326, 1986. —. Misses. Reprise 46358, 1986. Ochs, Phil. Farewells & Fantasies. Rhino 73518, 1997. —. The War Is Over: The Best of Phil Ochs. A & M 5215, 1988. Police. Every Breath You Take: The Classics. A&M 380,1995. R.E.M. Automatic for the People. Warner 9 45055-2, 1992. —. Eponymous. MCA 6262, 1988. —. Out of Time. Warner 26496. 199 1. Robinson, Smokey and the Miracles. The Best of Smokey Robinson & the Miracles. Motown 472, 995. The Rolling Stones. Beggars Banquet. Abkco 75392, 1968. —. Hot Rocks 1964-1971. Abkco 66672, 197 1. —. Some Girls. Virgin 39526, 1978. Scarface. The Diary. Rap-a-Lot Records 39946, 1994. Seger, Bob. Against the Wind. Capitol CDP 746060-2, 1980. Shocked, Michelle. Short Sharp Shocked. Mercury 834924, 1988. . —. The Texas Campfire Tape. Mercury 834581, 1986. Simon & Garfunkel. Bookends. Columbia 9529, 1968. —. Bridge over Trouble Water. Columbia 9914, 1969. —. Collected Works. Columbia 45322, 1990. Simon, Paul. Graceland. Warner 0-25447-2, 1986. —. There Goes Rhymin Simon. Warner 25589, 1973. Springsteen, Bruce. Darkness on the Edge of Town. Columbia CK 36318, 1978. —. The Ghost of Tom Joad. Columbia CK 67484, 1995. —. Greatest Hits. Columbia CK 67060,1995. —. Tunnel of Love Columbia CK 40999,1987. Sting. Fields of Gold: The Best of Sting 1984-1994. A&M 314540269-2,1994. The Supremes (and Diana Ross). Ultimate Collecxtion. Motown 13145304282, 1994. The Temptations. Ultimate Collection. Motown 3145305622, 1997. U2. The Best of 1980-1990. Island 314-524-613-2, 1998. —. The Joshua Tree. Island 422-842-298-2, 1987. Who, The. Quadrophenia. MCA 11 463, 1973. —. Tommy. MCA 11417, 1969. Williams, Hank. 40 Greatest Hits. Polydor 821233, 1978.