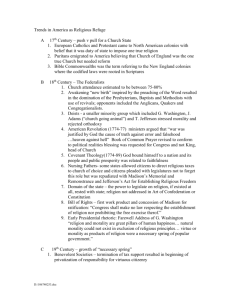

The Supply and Demand of Religion in the US and Western Europe

advertisement