Heroic Code Introduction.doc

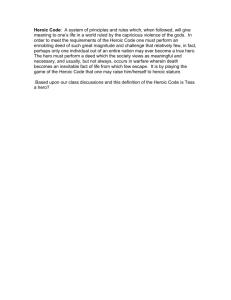

advertisement

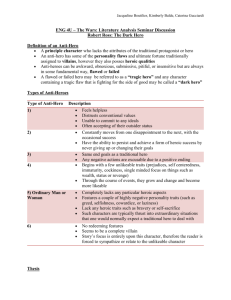

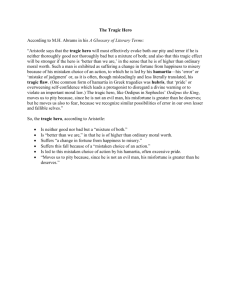

THE HEROIC CODE An Introduction to the Unit By Elizabeth Eaton CULTURAL HEROES Heroism comes in many forms, and it changes with the times. In ancient cultures, epic heroes performed glorious feats in battles, reportedly killed monsters, single-handedly decimated enemy tribes, and often gave their lives in the process. (This will become a refrain.) Religious heroes saved their cultures, established a system of beliefs based on faith and miracles, vanquished demons, and often gave their lives to save their people. Throughout history heroes stood for what was right, punished those who did bad things, and killed when necessary. For centuries, heroes were the good guys who served as a moral compass for us, the non-heroes. They spared civilians, women, and children, and centered their sights on evil men and cultures. They fought for the common good, knowing full well they might die in the process. They knew what they were put on this earth to do, and they voluntarily jeopardized their own safety and self-interest in the cause of duty and honor. They were most often modest, but fiercely intolerant of the bad apples that threatened our peace! For many, even today, this definition of heroism stands firm. We see heroism on television and on film, and we cheer those stalwart men and women on, even as they die nobly or celebrate victory at great personal cost. As time and cultures evolved (some might say devolved), however, other definitions of the cultural hero emerged. We began to celebrate the common man who was forced into heroic behavior either unwittingly, or against his will. (Interestingly, only a few women have been recognized in this category: the anti-hero). This hero may be physically weak, unassuming in appearance, and/or uncommitted to the common good. Sometimes the anti-hero is initially the bad guy who has seen the light and does the right thing at the last and (refrain!). An intriguing offshoot of the anti-hero is the paradoxically named existential hero, committed to nothing, understanding nothing, achieving nothing. Heroism can be ironic. A good person who begins his heroic quest with the best of motives finds himself corrupted by his achievements and the resultant adulation. If he dies in the process, that death (irony of ironies) benefits society by removing him from the world. An interesting mutation in the heroic code is the pop culture “hero,” admired because of wealth, celebrity, or notoriety. Sports and movie stars, personalities whose status was born of eccentric behavior or number of Twitter followers and even some newsmakers who terrorize the innocent are often embraced as role models. Fame is the name of the game. LITERARY HEROES You are already familiar with The Byronic Hero—that lascivious, misanthropic roamer patterned after the Romantic poet, George Gordon, Lord Byron. Byronic heroes show up everywhere, especially in Gothic and Victorian novels. Rochester, Heathcliff, Sydney Carton, Don Juan: they make attractive anti-heroes. LITERARY TRAGIC HEROES: An evolution from ancient times… to the Renaissance…to today. Aristotle set the standard in defining the tragic hero. Sophocles epitomized him in Oedipus Rex (Oedipus the King). The Greek Tragic Hero, by definition a man of high social status (a king, a general) who thought of himself as virtuous and valued honor above all: a. possessed a fatal flaw in his character (often hubris or overweening pride) that eventually causes his tragic downfall. Unfair though it seems, this flaw is his fate—given him by the gods. b. His flaw causes a mistake in judgment that brings about a total reversal of his fortunes and his dishonor (the perepetia). c. His punishment is his unbearably painful realization of what his mistake has cost him and those he loves (the anagnorisis). The Shakespearean Tragic Hero (Hamlet, King Lear, even Macbeth) possesses all of the qualities of the Greek Tragic hero with two important exceptions: a. He is responsible for his own downfall, with a little help from his enemies. The gods have nothing to do with his downfall, although he may try to blame them! b. He can be analyzed using the tenets of existentialism, a modern philosophical movement © Elizabeth Eaton 2014 Advanced Placement English/ Ardrey Kell High School, Charlotte, NC 1 THE HEROIC CODE An Introduction to the Unit By Elizabeth Eaton The Modern Tragic Hero (Willy Loman, Jay Gatsby, Mr. Kurtz) is nothing like his predecessors, except in the endurance of unbearable suffering. a. b. c. d. S/he represents us, the common wo/man, and like many of us, may not possess high social status or great virtue. S/he may never recognize what s/he did wrong to bring about calamity for self and others. S/he may be partially to blame for his or her suffering and demise, but society may have played an equal or greater role in his or her fate. Like the Shakespearean Tragic Hero, the Modern tragic Hero may be analyzed in terms of existentialism. The Unit includes: A Primer of Existentialism by Gordon Bigelow (article) Hamlet by William Shakespeare (Heroic sub-type: The Revenge-Seeker) Genre: Drama—Play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead by Tom Stoppard (Heroic sub-type: The Anti-Hero) Genre: Drama—Play The Wall by Jean-Paul Sartre (Heroic sub-type: The Anti-Hero) Genre: Fiction—Short Story A Clean Well-Lighted Place by Ernest Hemingway (Heroic sub-type: The Anti-Hero) Genre: Fiction—Short Story The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock by T.S. Eliot (Heroic sub-type: The Anti-Hero) Genre: Poem Macbeth by William Shakespeare (Heroic sub-type: The Ironic Hero) The Freudian Approach to Literature How to Read Literature Like a Professor by Thomas Foster AP Test Preparation Poetry focused on the Heroic Code Independent Reading: Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (Heroic sub-type: The Ironic Hero) Genre: Fiction—Novella © Elizabeth Eaton 2014 Advanced Placement English/ Ardrey Kell High School, Charlotte, NC 2