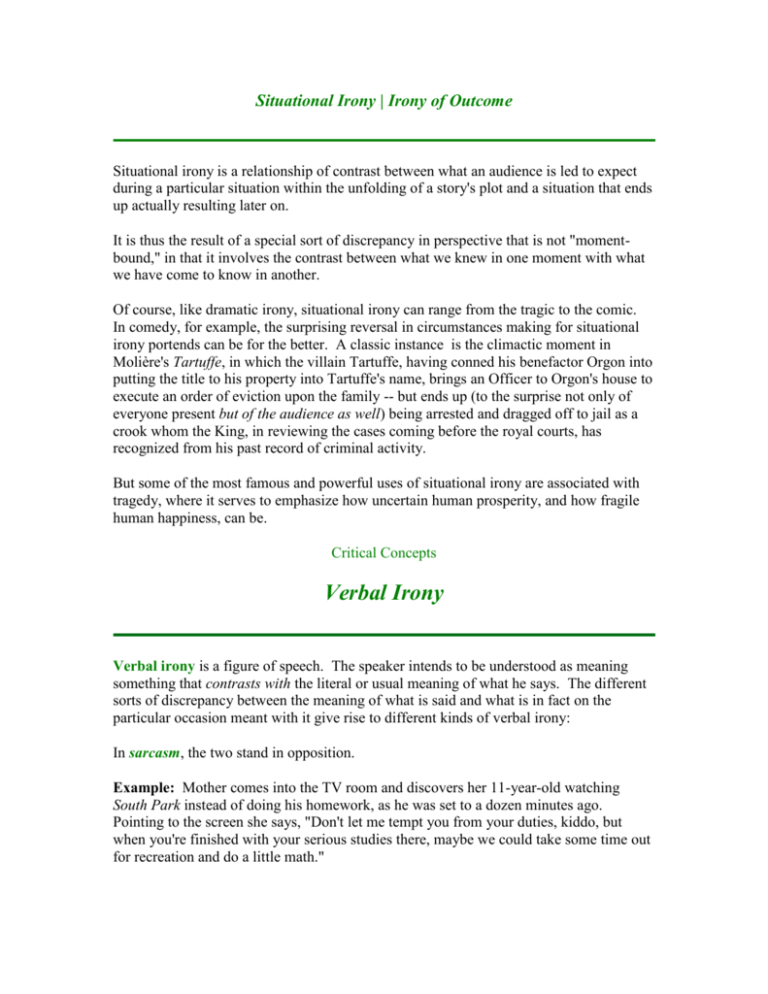

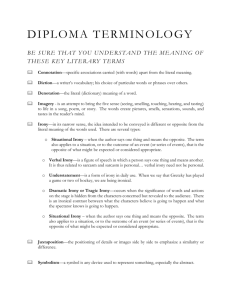

Situational Irony | Irony of Outcome

Situational irony is a relationship of contrast between what an audience is led to expect

during a particular situation within the unfolding of a story's plot and a situation that ends

up actually resulting later on.

It is thus the result of a special sort of discrepancy in perspective that is not "momentbound," in that it involves the contrast between what we knew in one moment with what

we have come to know in another.

Of course, like dramatic irony, situational irony can range from the tragic to the comic.

In comedy, for example, the surprising reversal in circumstances making for situational

irony portends can be for the better. A classic instance is the climactic moment in

Molière's Tartuffe, in which the villain Tartuffe, having conned his benefactor Orgon into

putting the title to his property into Tartuffe's name, brings an Officer to Orgon's house to

execute an order of eviction upon the family -- but ends up (to the surprise not only of

everyone present but of the audience as well) being arrested and dragged off to jail as a

crook whom the King, in reviewing the cases coming before the royal courts, has

recognized from his past record of criminal activity.

But some of the most famous and powerful uses of situational irony are associated with

tragedy, where it serves to emphasize how uncertain human prosperity, and how fragile

human happiness, can be.

Critical Concepts

Verbal Irony

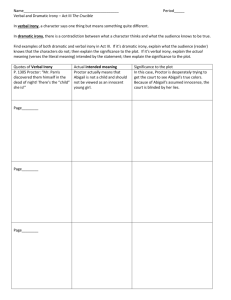

Verbal irony is a figure of speech. The speaker intends to be understood as meaning

something that contrasts with the literal or usual meaning of what he says. The different

sorts of discrepancy between the meaning of what is said and what is in fact on the

particular occasion meant with it give rise to different kinds of verbal irony:

In sarcasm, the two stand in opposition.

Example: Mother comes into the TV room and discovers her 11-year-old watching

South Park instead of doing his homework, as he was set to a dozen minutes ago.

Pointing to the screen she says, "Don't let me tempt you from your duties, kiddo, but

when you're finished with your serious studies there, maybe we could take some time out

for recreation and do a little math."

Example: Dad is finally out of patience with picking up after his son, who can't seem to

be trained to put his dirty clothes in the hamper instead of letting them drop wherever he

happens to be when he takes them off. "Would Milord please let me know when it

pleases him to have his humble servant pick up after him?"

The term comes directly into English from the Greek sarkasmos, which in turn derives

from the ugly verb sarkazsein, "to tear the flesh" (used of dogs). (You may have seen the

root sark-, "flesh," in sarcophagos, a coffin ["flesh-eater" -- delightful idea!]). It's

difficult to know whether this originated in the metaphorical idea that someone who uses

sarcasm is "cutting up" the person or thing that's the target of his remark, or whether it

refers to the more nearly literal idea of his being so angry that he's gnashing his teeth so

passionately that he ends up biting his own lips! Either way, the idea that he is in a

savage mood. But note that the term sarcasm in the technical rhetorical sense we've

constructed (meaning the opposite of what you say) does not necessarily carry the

implication that the speaker is being critical or feels hostility, as in the original Greek

sense of the term, which carries over into our contemporary everday sense of the word.

Bitter or hostile sarcasmis only a special case of "sarcasm" as we are defining the term

here, which is broad enough to cover cases in which the speaker is paying a compliment

or being gentle.

Example: "My, you've certainly made a mess of things!" could be said in

congratulations to someone who's just graduated summa cum laude, or to a hostess who

presents a spectacular dish prepared with obvious care and skill.

Examples: Chances are you actually read the first two above (the parental

remonstrances) as not altogether nasty. They could be delivered this way, but there's

quite a range of tones in which they might be couched. Many are the modes of nagging!

Try delivering each remark as furiously hot ("savagely flaying," "flesh-tearing"); then as

resigned grumbling; then as exasperated, out-of-patience; then as wheedling and whining;

then as earnest pleading; finally as gently ribbing. The latter actually amounts to an

ironic use of verbal irony: I pretend to be mean (by pretending to be respectful), but I'm

really not. All this reminds us that detecting irony is only a first step (though essential) in

registering what's going on. When reading, we've got to be attending to every available

clue to voice.

In overstatement, the meaning that ordinarily attaches to what is said is an exaggeration

of what the speaker uses it to mean.

Example: Someone tells us of an occasion on which he told an off-color joke about a

grandmother and then realized to his surprise that his own grandmother, a prim and

proper lady, happened to be standing right behind him. "I literally died," he says.

Well, if he literally died, we should be pretty spooked, because we're face to face with a

corpse! The word "literally" here is itself being used figuratively, to mean something like

"really" -- itself in the diminished sense of "not really but almost," or "intensely". And

the phrase as a whole means something like "I almost fainted." Fainting is (often) a

symptom of shock (which in some forms can kill), and is like death in involving loss of

consciousness. Fainting falls considerably short of death, but the truth here is that the

teller didn't even actually faint, either, but almost fainted -- felt as if he were going to

faint. He didn't lose consciousness altogether, but experienced some disorientation and

dizziness that was something on the verge of what one might feel just before fainting.

Note that this example of overstatement also incorporates metaphor and simile. It is the

comparisons of wincing to fainting and of fainting to death that constitute the continuum

along which the terminological displacement through exaggeration takes place.

Overstatement is still referred so sometimes today by the name given it by the ancient

Greek students of rhetoric: hyperbole ("hy-PER-bo-lee"), from hyperballein (to exceed,

hit beyond the mark, from hyper over + ballein to throw, cast). The adjective form is

"hyperbolic."

Examples:

"The speaker was somewhat hyperbolic in his praise of the deceased."

"I got bored by his hyperbolic remarks."

In understatement,

Example: We visit our friend in the hospital. We know from his wife that the prognosis

is bad, and also that our friend has been informed of his condition. When we enter, we

ask him how he's feeling. "Well," he says, "I have been better."

Litotes ("lie-TOW-teez," from Greek litos, simple, plain) is a special form of

understatement in which we affirm something by negating its contrary.

Examples:

"She's not a bad cook." ==> She's quite a good cook.

"He's not the world's best speller." ==> He's very poor at spelling.

Verbal irony is not the same as dramatic irony. To see why, let's contrast it with one of

the starkest kinds of verbal irony: sarcasm.

In sarcasm, the meaning of what I say and what I mean with it stand in opposition.

"Terrible weather!" my colleague exclaims as we pass between buildings on a beautiful

spring day.

Of course the situation is important as a cue to what she means. As with metaphor ("")

and metonymy ("All hands on deck!"), there is a discrepancy at work that tells us that

what is said can't be taken literally. With metaphor and metonymy the discrepancy is

ordinarily internal to the discourse -- there is a logical-grammatical disjunction in the

phrasing that makes nonsense of the whole if we take the parts in their usual sense. But

with the various forms of verbal irony the tip-off is not a category violation but some

inconsistency between the overall sense of what is said and the properties of the situation

it is understood to refer to. This is probably why it may at first be hard to see exactly

what the difference is between verbal irony and dramatic irony: in both there is a

contradiction between what the speaker says and the situation we (as the audience) see

what is spoken to be uttered in. But there is a difference, and a crucial one.

Let's recall the scenario we began with. It's a sparkling day, the forsythia is in full bloom,

the redbuds are starting to show pale purple, and even a few hyacinths are still out. The

breeze is crisp but not too cool. My colleague is beaming, obviously in good cheer. She

sees me approaching, draws her brows into a frown, and says with a grin, "Terrible

weather!" Now suppose it just so happens that, unbeknownst to her, I'm afflicted with an

allergy triggered by a pollen released by some shrub in this season. I've been up all night

wheezing and sneezing, and I'm jittery as the dickens with the antihistamines I've been

dosing myself with in a vain attempt to get relief. I know what she means: it's great to be

outdoors in these wonderful days. I'm in a rush to class, though, so I grin and say, "I

couldn't agree more!" but without pausing to bewail my troubles.

Here we have, in separate instances, verbal irony (her pronouncing the weather vile as a

way of celebrating how wonderful it is) and dramatic irony (for me, but not for her, the

weather is vile, but she doesn't know that). We can now bring the difference into focus:

In verbal irony we have a discrepancy between the meaning of what the speaker

says and what the situation indicates the speaker means by it.

In dramatic irony we have a discrepancy between a speaker's understanding of

the full situation and the situation as some audience understands it.

In the example above, this audience was the person spoken to, but in a story or play it could be the reader

or theater audience, even if all of the characters are in the dark about what the full extent of the relevant

situation happens to be.

And what about my reply ("I couldn't agree more!")? Actually I don't agree at all -- I'm

just saying this, to be polite, and to get on my way. Perhaps I'll let my friend in on the

irony later on, but not now, since I'm almost late for class. Is this an instance of of

"verbal irony"? It's certainly verbal, and I understand what I say ironically, but it's not

something that falls under the concept of verbal irony as that term is conventionally

used (Note). Rather it's an instance of a species of hypocrisy that we call "conscious

hypocrisy."

In conscious hypocrisy the speaker does not intend the hearer to understand the

facts of the situation that betray the meaning of what is said. (We might stretch

the sense of the verb "to mean" and say that the speaker means one thing for his

hearer, but another for himself.) In verbal irony the speaker intends to be

understood as meaning something that contrasts with the literal or usual meaning

of what he says. In hypocrisy the speaker intends to be understood as meaning

what his utterance would ordinarily and literally mean, even though he is aware of

the fact that the situation is at odds with this.

Note that if we are going to talk this way we are using the term "hypocrisy" in a broader sense than it

typically is in today's everyday discourse. There, to call something "hypocritical" is generally to subject it

to fairly severe moral censure, whereas the deception here is unlikely to strike us as anything invidious. It's

simply not to the point, in the circumstances of the transaction (my friend's elated greeting) to call a halt to

our other business and instruct her in her error. The deception was out of consideration to our mutual

convenience. Later on, if occasion arises, I can cut her in on the dramatic irony she was involved in, which

will probably be as humorous to her as it was to me. For now, my pretense of agreement is in the spirit of

"Let it pass" -- a silent pardon of a humorous faux pas. So when we call this "hypocrisy," we are

constructing a more general sense of the term than the one we may be used to in everyday discourse.

We can certainly imagine situations in which morally censurable forms of hypocrisy are at work. They

will exhibit the same general form, distinct from that of verbal irony: the speaker knows something about

the situation that he obscures from the hearer by putting forth an utterance with a meaning that he doesn't

sincerely mean. Whether a speech act of this form (we could call it "hypocrisy in the rhetorical sense")

counts as hypocrisy in the morally censurable sense (what the term typically means in everyday discourse)

depends on our assessment of the motives of the speaker under the circumstances.

To drive home the idea that verbal irony is not the same thing as hypocrisy, consider these situations.

Notes

It's certainly verbal, and I understand what I say ironically, but it's not something that

falls under the concept of verbal irony as that term is conventionally used. The phrases

a community adopts to indicate the notions it finds use for do not always turn out to be

suitable for all the situations reality contrives to confront us with. Here we find ourselves

involved in still a different kind of irony, for which the conventional term is situational

irony. We would expect that the phrase "verbal irony" would cover such situations, but it

turns out that it doesn't. This kind of thwarting of expectation by outcome is a common

plot element in literature (as in real life). <Return.>

Critical Concepts

Dramatic Irony

Dramatic irony is a relationship of contrast between a character's limited understanding

of his or her situation in some particular moment of the unfolding action and what the

audience, at the same instant, understands the character's situation actually to be.

It is thus the result of a special sort of discrepancy in perspective, and hence is "momentbound." There is on the one hand how things appear from a point of view that emerges

within the action at a given moment, and which is constrained by the limitations of an

individual's history up to that moment. (In fiction, this will be the picture held by some

character -- say, the protagonist of a drama.) There is on the other hand a synoptic point

of view that takes in the whole of an interpersonal history, part of which is unknown to

that individual at the particular moment in question. For dramatic irony to emerge, some

consciousness (in fiction, this will be the audience's) must be simultaneously aware of

both perspectives.

Of course, dramatic irony as such is not necessarily tragic. In comedy, for example, the

change in circumstances dramatic irony portends can be for the better. A classic instance

is the climactic scene in Molière's Tartuffe, in which the villain Tartuffe, responding to

the pretended invitation of his patron's wife, carries on contemptuously (and accurately)

about the Orgon's gullibility, unaware that the latter is hiding beneath the table on which

he's trying to seduce the lady. A famous example of serious comic dramatic irony takes

place at the climactic moment of Mark Twain's novel The Adventures of Huckleberry

Finn.

But some of the most famous and powerful uses of dramatic irony are associated with

tragedy, where it serves to emphasize how limited human understanding can be even

when it is most plausible, and how painful can be the costs of the misunderstandings, in

some sense inevitable, that result.

Some pointers to instances of dramatic irony in Sophocles' Oedipus the King.

The term "dramatic" as incorporated in the term dramatic irony has nothing to do with

"dramatic" in the sense of "sensational" or even "emphatic" or "obvious" — as when the

newscasters breathlessly announce some "dramatic events" in Athens or wherever.

Dramatic irony, whether on stage or in a poem or story, can perfectly be quite

unassuming or subtle. It need only be interesting. (Some of the kinds of interest that can

attach to it are discussed later on in this article.)

Some but not all cases of dramatic irony involve unconscious hypocrisy.

In unconscious hypocrisy the speaker intends to be understood as meaning what his

utterance would ordinarily be understood to mean, but is unaware that the situation is at

odds with this meaning. (In conscious hypocrisy, benign or malign, the speaker is aware

that the situation is at odds with what he gives himself out to mean. That is, he intends to

deceive the hearer.)

A classic instance of dramatic irony that involves no hypocrisy takes place in the scene in

which Oedipus reproaches his brother-in-law Creon, whom he mistakenly but plausibly

believes to have conspired to bring him under suspicion of having killed the former king

of Thebes in order to have him expelled from the city so as to be able to take over the

kingship in his stead. He tells Creon that a man is a fool if he thinks that he can sin

against his kinfolk and escape the wrath of the gods. We note that the warning is phrased

as a universal: it applies to any person. Oedipus is unaware that he himself has slain his

own father (the very same king, no less) and committed incest with his mother. The

audience, however, in the moment it hears Oedipus make this declaration, knows (1) the

facts about Oedipus' parricide and incest, (2) the fact that Oedipus is unaware of these,

(3) the fact that these transgressions will eventually be revealed before all Thebes, (4) the

fact that Oedipus will suffer terribly at this revelation, and (4) the fact that the divine

order (in virtue of the various prophecies and circumstances of their fulfillment) is firmly

implicated both in the commission and the discovery (hence "punishment") of these

crimes. It is this discrepancy between what Oedipus understands his words to apply to

and what the audience understands their scope actually to be that constitutes the effect the

dramatic irony.

At the same time, it would be grotesquely stretching the concept of "unconscious hypocrisy" to say that

Oedipus is guilty of that at this moment.

One reason is that even at this moment we know that Oedipus is the kind of person who, if it were

demonstrated to him that he has "sinned against kin" in the ways described, would immediately

recognize (as he eventually does) that the principle applies to him. That is, he may be mistaken

about the facts, but he is not committed to a double standard.

Another reason is that, under the circumstances in which he happens to have arrived in the

situation in which the audience knows him to be, Oedipus here can in no way said to be selfdeceived.

An effect of this is that Oedipus retains his ethical dignity, and presumably for the original

audience as well as for us -- in spite of the fact that they (unlike we) are in agreement with him

that intention not to commit the prophesied abominations does not absolve him from the pollution

of having done so nevertheless.

A classic instance of dramatic irony that definitely does involve unconscious hypocrisy is

what Torvald Helmer unwittingly reveals about his character in the climactic scene of A

Doll's House, in his reaction to Krogstad's first letter, informing him that his wife Nora

has forged a promissory note in her (now dead) father's name in order to provide

collateral for a loan. There are in fact several respects in which he shows himself to be

an unconscious hypocrite.

In his outburst -- "So this is how I'm repaid for having shielded your corrupt

father from his misdeeds. All his moral weaknesses have come out in you" -- he

inadvertently reveals that he himself had committed perjury in covering up for

Nora's father (whose daughter he wanted to married) when, as a young lawyer, he

had been commissioned by the city authorities to look into allegations that Nora's

father had mishandled (read: embezzled) public funds. Her ignorance of the law,

in his eyes, is no excuse. But of course he himself knew perfectly well that his

own affidavit as the special investigator of Nora's father's case was criminal, and a

betrayal of the public trust to boot.

He declares her morally unfit, because of this lie on her part, to come into contact

with their children, who will be "infected" with her "moral disease." Yet he sees

no inconsistency in insisting that they two of them pretend to the world at large

that nothing is wrong in their relationship -- a collaborative fiction that could not

help to register with the children.

He complains that he will now be a puppet in Krogstad's hands, because the latter

can force him to do anything he pleases, by threatening to exposing his wife's

criminal act. This completely elides the fact that these threats cannot force him to

do anything: they can be effective only if he decides to give into them. By

revealing that he is resolved to comply, he indicates he has no objection, in his

own case, to involve himself in covering up any number of improper acts on his

part demanded by the blackmailer.

The dramatic irony here strikes us as involving unconscious hypocrisy.

Unlike Oedipus, Helmer's conception of his own identity commits him to a double standard.

And we are conscious not only that, if he were challenged, he would go to some lengths to deny

this ethically disquieting fact, but that he is even at this moment engaged in deceiving himself

about the sort of person he is, on the principles he invokes in condemning his wife.

Hence, the fact that Helmer never realizes how unfair he is does not absolve him, for us. In our

eyes, he has forfeited the dignity he lays claim to.

Contrast verbal irony and situational irony.

Return to the Index to the Glossary of Critical Concepts.

Suggestions are welcome. Please send your comments to lyman@ksu.edu .

Contents copyright © 1999 by Lyman A. Baker.

Permission is granted for non-commercial educational use; all other rights reserved.

This page last updated

.

Critical Concepts

"Static" and "Dynamic" Characterization

Curiosity about the possibility and conditions of "change in identity" has been

remarkably intense, in fiction and in psychology, during the last century. In talk about

literature, this has led to the development of a crude but useful terminological distinction

of two sorts of characterization: "static" and "dynamic." A static character, in this

vocabulary, is one that does not undergo important change in the course of the story,

remaining essentially the same at the end as he or she was at the beginning. A dynamic

character, in contrast, is one that does undergo an important change in the course of the

story. More specifically, the changes that we are referring to as being "undergone" here

are not changes in circumstances, but changes in some sense within the character in

question -- changes in insight or understanding (of circumstances, for instance), or

changes in commitment, in values. The change (or lack of change) at stake in this

distinction is a change "in" the character (nature) of the character (fictional figure).

If a character inherits a million dollars from a rich aunt in the course of a story, this may

or may not result in the sort of change in his personality or values or in his general

outlook on life that would make him count as an instance of dynamic character in this

special sense. (The same goes if his impressive stock portfolio goes up in the smoke in a

bear market.) He might remain the same cheerful, humble, easy-going, out-going fellow

he was before this fortunate turn of events. Or he might remain the same bitter, cynical,

resentful, suspicious, selfish person he had always been. Or he might continue to be the

same smug, arrogant snob he's already exhibited himself to be. In any of these cases,

we'd have an instance of static character. Of course such a drastic change in one's

circumstances (whether good fortune or bad) might motivate a change in one's outlook on

life. And if -- but only if -- it results in this sort of change, we are confronted with a

dynamic character.

This means that, while we certainly do want to take account of what the story implies as

the motivation of this "change in character," we don't want to include these causal or

conditional factors as part of our description of what the change in character consists in.

(A "factor" is not an "element.") We'll want to avoid the temptation to substitute

externals (which are often explicit and obvious) for internals (which are often implicit,

and take some work to get a clear grasp of). It is surely true that Ivan Ilych, in Tolstoy's

novella The Death of Ivan Ilych is greatly changed in the course of his dying. But we

will not do ourselves justice if we are content with merely recalling the details of his

worsening physical condition, and never get round to reflecting on just what are the exact

changes in assumptions and feelings he undergoes between his awareness that he is not

(physically) well and the moment of his death. Among other things, we'll miss the

central paradox of the story, that while he was "doing well," he was spiritually gravely ill,

and that in gradually taking stock of this and in facing up to some newly emerging

concerns, he eventually achieves a soundness of spirit more profound than that which he

left behind with his childhood. (Even the formulation just given is too general to do

justice to what we should take stock of, on the level of particulars, in the change of

character Tolstoy wants to acquaint us with.)

Note, by the way, that what is going on "inside the body" counts as "external

circumstance" from the point of view we are adopting here. It is not a "change internal to

the character" in the sense in which we are using the terms "internal" and "character" at

the moment!

Some tips on using these concepts in a clear and tactful way

First off, we don't want to confuse the distinction between static and dynamic

characterization with the distinction between flat and round characterization.

Secondly, there are some important other senses of the phrase "dynamic character" in

common use that have nothing to do with the term dynamic character in the particular

sense with which we are concerned here. They are perfectly good in their place, but we

have to take care not to confuse them with what we've been talking about.

If we say of someone we have met that "she is a dynamic character," we may be using

this to mean that she "has a dynamic personality." We want to say that she is "full of

energy," perhaps, and that she has "an appetite for action," for "getting things done."

Alternatively, we might mean that she is a "great motivator," able to inspire others to

action. (We might of course mean both. But they are distinct: a person could be quite

full of energy, and burning to get things done, but a real put-off as an organizer, a

miserable motivator of others.)

Of course, we may meet with such a character in a literary work, but when we do we

would be well advised to employ the term "dynamic personality" or "dynamic person,"

rather than "dynamic character," because the latter is already "pre-empted" in talking

about literature. (If we were talking computer talk, we'd say that inside this program that

term is "reserved.") In talk about literature, the term "dynamic character" means simply a

character who undergoes some important change in the course of the story.

Thus a character who is portrayed as a "mover and shaker," and is that way throughout

the story, is a static character, in the literary-critical sense of the term. A fictional

character with an "inspiring personality" would qualify as a dynamic character, in the

literary-critical sense of the term, only if she became that way -- or ceased being that

way! -- in the course of the story.

Moreover, within literary critical discourse, these terms are meant to be purely

descriptive, not evaluative. That is, "dynamic" characters are not necessarily better, in

narrative art, than "static" ones.

The question, from the aesthetic standpoint, is whether a portrayal is what is called for in

light of the work as a whole, and whether it is done skillfully or ineptly, interestingly or

boringly. (Indeed, even a persistent bore can be portrayed in an interesting -- for

example, quite comic -- fashion.) Even in works intensely interested in the way in which

personality can reformulate itself, subordinate characters are likely to be "static," if for no

other reason than that to do otherwise would be to distract the reader from what the story

is designed to get us to notice. In this special literary-critical use of the terms, "static" is

not, for example, synonymous with "sterile" or "hung-up" or "stultified." (When an

author "develops a character" as "static," that does not mean, at least not necessarily, that

we are faced with a case of "arrested development.") Similarly, "dynamic" in this usage

says nothing about whether a character is what is popularly referred to as a "dynamic

personality" -- i.e., an individual with a power of impressing others, energizing them to

action or compelling their admiration. (Such a person appearing in a fictional work, in

fact, might well provide an instance of a "static" character in the sense in which we are

using the term here.)

And from the ethical standpoint, as well, it is important not to suppose that "dynamic"

characters are superior to "static" ones. Whether any change -- in personality or

character, just as in society, or medical condition -- is good or bad, depends on two

distinct kinds of factors: the framework of values within which we assess states of

affairs, and what happens to be the initial state of affairs. This means that a change in

personality may be for the better -- but it just as well may be for the worse. And the

same goes for a refusal to change: this may signify an intellectual or moral failure, but it

may be just what is called for. After all, if we are confronted with a temptation, the hope

is that we can muster the resources of insight and resolve to resist giving into it. If a

fictional character does this, he or she is a "static" character, and this "stasis" of character

in the face of circumstance is a virtue.

In fact, it is precisely because change in identity can be good or bad, depending on

circumstances and on the framework of evaluation, that it is often useful to classify plot

in terms of characterization.

The point of the distinction

Noticing which pole it may be towards which an author has decided to steer in

characterizing a given character is useful -- but only if we are prepared to use what we

notice as a starting point for these new curiosities.

(1) What, exactly, is the change we are to take stock of as having occurred?

How precisely are we to understand the motivation of this change?

How is it distinct from what the change itself (in character) consists in?

What's the extent of this change? (That is: what we first notice may be only a

piece, or an aspect, of the fuller change are invited to notice.

(2) How is it that the author's decision to treat this character as he or she has an

appropriate one, given what is called for from the standpoint of the focus and purpose of

the story as a whole?

(3) Or, put the other way around: supposing the author decided appropriately, what can

we infer the overall focus of the story must be? What are the issues it is crafted to raise,

and why are these worth our attention (if they are)?

What is important about the change that a dynamic character exhibits? And why

is this important?

Why is it important that this static character does not undergo an important

change?

(4) If we feel, provisionally, that the author's decision is not effective, then it must be we

sense the story is "torn between" alternative directions in which a more "clearly

conceived" story might go.

We might then try to clarify for ourselves what would be at stake in deciding to

reshape the story along one or another line of possible development.

But we should also keep open to the possibility that we have not yet adequately

grasped what the overall aims of the story in fact are.

Related discussions.

Character and Characterization

"Flat" and "Round" Characterization

Return to the Index to the Glossary of Critical Concepts.

Suggestions are welcome. Please send your comments to lyman@ksu.edu .

Contents copyright © 2000 by Lyman A. Baker.

Permission is granted for non-commercial educational use; all other rights reserved.

This page last updated

.

Critical Concepts

"Flat" and "Round" Characterization

Often we think of "characterization" as akin to "portraiture" in drawing and painting, or

in sculpture. One of the decisions a portraitist is confronted with is: in how great detail

shall I execute this portrait? Should I sketch it in simple terms, or should I strive for

complex accuracy of detail? Should I work in monochrome (sepia ink, or pencil, or black

oil; on beige paper, or white-primed canvas), or should I do it in color (pastel pencils, or

watercolor, oil-based paint)? Should I work on a two-dimensional surface (paper or

canvas) or construct something in three dimensions (casting bronze, carving stone or

chiseling stone)?

Writers face analogous decisions, but (as we shall see) the analogy goes only so far. One

limitation (we'll have more to say on this in a moment) is that in fiction the writer is not

starting from an existing reality, which he aims to represent, but making things up. That

is: complexity in characterization, in fiction, is not something that confronts the writer as

a matter of how much of what is already independently out there should I strive to

capture in my representation of it, but more a matter of how complex does this character

need to be? The criterion of "need," that is, is not accuracy (it might not be that for a

painter doing a portrait for a client, but it can be and often is). It is something else -- "the

needs of the work as a whole," which itself is also something the writer generally end up

discovering in the process of experimenting with "what to put in" and "what to leave

out." In fact, many writers report that a large part of their "creative process" amounts to

deciding what to cut out from successive drafts. Partly this is a matter of not letting

things get out of control (having an interesting subordinate character "get out of

proportion:" and "run away with the story"). Partly it is a matter of deciding what is

superfluous to include because what it is there for is already adequately communicated

by other details. But always it is guided by an emerging "feel" for what the situation is

that (for some reason) they feel the impulse to ask their reader to imagine. You discover

what this situation is that you "want" by experimenting with variations and discovering

that you don't want them. It may gradually dawn on you why you are so interested in a

situation with just these properties and why some close relative of it misses "the mark."

If you do -- if you arrive at some reflective grasp of why you want to ask attention for this

situation rather than that -- then this sort of insight may be one of the last things that the

whole process results in, for you, the author.

On the assumption in mind that what is of deepest interest in a story is "defined by"

exactly what the explicit and implicit facts of the story have been decided to be, serious

readers in turn cultivate a careful attention to what the exact details are that the story

consists of. If we want to know "what a story is there for," we'll look to see (among other

things) what characters are included in it. And if we're looking a characters in terms of

their "reason for being" in the story, one of the things we'll be interested in is the relative

degree of complexity with which different characters are endowed.

Perhaps it will be better if we think in the first instance in terms rather of “flat or round

characterization than in terms of “flat or round characters,” and then say, derivatively,

that a round character is a character whose characterization by the author is (relatively)

“rounded” rather than (relatively) “flat.” We have to keep in mind not only that we’re

dealing here with a matter of degree rather than with discrete categories, and that we’re

dealing with metaphor (hence the reminder quotes at the end of the last sentence) but that

what’s at stake is more manner of portrayal than what is portrayed, or (even better) of

creation rather than representation. After all, it’s not as if these fictional critters had an

independent prior existence that a writer could either capture fully or lay hold of only

superficially. They are what the author decides to make them. For example, in the story

"Gimpel the Fool," I.B. Singer makes Elka and Gimpel by deciding what qualities he will

give them. It’s his decision to make them relatively complex (as pretended persons) or

relatively simple (i.e., the way he goes about characterizing them) that determines

whether they come across as (relatively) “round” or (relatively) “flat.”

But what exactly is it about the way he goes about constructing them that determines

whether they end up "round" or "flat"?

We might be tempted to conclude that Elka is round “because the author gave us many

details about her.” It is certainly true that Singer gives us many details about Elka, and

that these details are quite vivid. They make her "come alive" for us: she's certainly not

"wooden"! But it's not the number of details that makes for a round character, or even

the vividness of those we are served up. If it were simply a question of vividness, then

there could be no vivid flat characters, but literature abounds with them. Pangloss in

Voltaire's philosophical tale Candide is a hilarious example, just as Fagin in Dickens'

Oliver Twist is a villainous one.

To begin with, the flat/round distinction has to do not with the richness of detail, but with

the traits these details express. It's important to see, though, that it is not just a matter of

the clarity with which express the character's personality and ethical features comes

across. If this were so, it would be the case that we would end up with only a dim or

vague or confusing notion of what makes flat characters tick, but this is surely not the

case, as the same examples (Pangloss and Fagin) will serve to drive home. Certainly we

don't have any problem arriving at a conception of how Elka thinks and feels: we are not

just confined to bare information about what she says and does. But the fact that we

know what type of woman Elka is (self-centered, with strong physical appetites, shortsighted) does not suffice for her to count as a flat character.

Nor is the flat/round distinction is a matter of the number of traits. It is true that round

characters will have to exhibit more than one trait, it is also true that flat characters are

often possessed of a multiplicity of distinguishable traits. The key point in the flat/round

distinction, however, has to do with the kind of relation a character's traits bear to one

another. Consider the character's we meet in Vonnegut's story "Harrison Bergeron.."

Martha is clearly simple. But it is not the fact that she is a simpleton that makes her an

instance of a flat character; it is rather that this is all she is: dim-witted. Her husband

George is definitely not a simpleton, but the recipe by which he is drawn is still quite

simple. He is intelligent, and endowed with the natural instincts that accompany

intelligence: a spontaneous appetite for tracing out implications, noticing

contradictions. He suffers, but not in virtue of any internal inconsistencies of personal

nature -- only because his society is determined (in its pursuit of abject conformity on the

part of all "citizens") to inhibit his thinking, by subjecting him to periodic, but

unpredictable, distractions through the headset he is obliged to wear. Notice that even

Martha's and George's son Harrison himself counts as a flat character, even though his

outstanding characteristic is that he’s a “well-rounded” collection of perfections. The

relevant question is: how rich a personality do we have here? Harrison is simply

“perfect” (handsome, strong, graceful, brilliant, courageous) and single-minded in his

mission: there’s no nuance, and there doesn’t need to be. We can enumerate

distinguishable traits, but these are all-of-a-piece: he is (simply) a supremely talented

individual. (This is what makes him, in the political culture in which it is his misfortune

to have been born, an Enemy of the State.)

So what kind of relationship do the traits of a round character bear to each other? There

has to be a certain kind of richness that we call "complexity." The various traits of a

"round" character will not all line up in some coherent hierarchy. Harrison's

"multifaceted natural excellence" expresses itself in a comprehensive totality of distinct

realms (physical, intellectual, moral), and within each of these realms we see a wealth of

distinct aspects of excellence (as to the physical, for instance, he is agile, graceful, swift,

strong, and beautiful; the brilliance of his intellect presumably not only logical

competence but imaginative powers and aesthetic sensibility, not only tactical cleverness

but [we suppose] strategic depth; ethically he is evidently courageous and resolute as well

as clear-sighted about the rights of individuals to realize their potentials [i.e., not only

strong of will but committed to presumably sound values]). This systematic unity of

conception means that all these various traits are mutually harmonious and, in the end,

reducible to a simple overall formula, in this case, something like "Versatile Natural

Talent." But a round character, like a "complicated personality" in real life, tends to be

subject to internal stress, as the result of adherence to values that, at least in the situations

with which the character is confronted, are not easily reconciled, or as the result of

inclinations and appetites that pull in contrary directions. These are often (but not

always) characters who are harder to figure out, not (at least not necessarily!) because

they are confusingly or vaguely conceived by their authors, but rather because they are

too "rich" to be reduced to a simple formula, and this because the implications of their

psychological and ethical traits, as these are called into evidence within the situations in

which they find themselves immersed, not only have to be "thought out," but typically

turn out to be "balled up" -- tangled and conflictive. This is the force of the metaphor of

"depth" involved in the idea of "roundness."

Note that we can imagine a flat character who is chronically indecisive. This could be his

leading trait, his "defining essence": whenever he is faced with a decision (whether to

marry, to buy a car, to go to Mexico for vacation, etc.), he ties himself in knots thinking

of a host of pros and cons, and ends up procrastinating his way into a decision by default

(the girl leaves in disgust, the car gets sold to someone else, the two weeks runs out, etc.)

But a character is capable of being faced with a complex decision -- of really responding

(eventually) to the complexity of the issues attaching to it -- we must be faced with

character who is multidimensional in a sense that goes far beyond the monolithic

perfection of Harrison Bergeron.

The issue is thus whether a character is drawn with some complexity or whether it is the

embodiment of a rather simple set of traits (sometimes even just one or a couple, as in the

stock character of the "braggart soldier" in Roman and Renaissance drama. Note, though,

that it's possible for even this simple stereotype to be developed in ways that result in a

pretty rich portrait: think of Shakespeare's Falstaff (in Henry IV Part I) — there's

someone who's arguable "round" in more than the physical sense (which of course he is

also, being quite a hefty sack of flesh).

Flat is not worse than round.

Related discussions.

Character and Characterization

"Static" and "Dynamic" Characterization. (It is essential to appreciate how the

distinction between static and dynamic characters is not the same as the distinction

between flat and round characters.)

Critical Concepts:

Allusion

An allusion is an indirect reference to something outside the immediate context of the

present discourse. For example, in moaning to your grandmother about the state of your

bank account, you might remark that it's as depleted as Great Uncle Billy's back forty

back in the Dust Bowl. This is a simile, of course, but it won't make any sense to

someone who doesn't already know what the Dust Bowl is. And if your grandmother has

memories of Uncle Billy's miseries in those days, what you say will take on a vividness

that it probably wouldn't for people who weren't there, or who haven't heard their tales of

woe.

An example like this reminds us that allusions often depend on a shared body not just of

experience but of experience mediated by a common stock of stories. They are

dependent, for their work, upon communities that are familiar not so much with the same

vocabulary but with a body of standard narratives, that circulate and re-circulate. So,

many of you will have no difficulty of making sense of a remark like "His wits are as

dried up as the Wicked Witch of the East," or (speaking of a politician on election eve)

"Let's hope tomorrow we can say Hasta la vista, baby." But others, who've never heard

how the tornado sets down Dorothy's house in The Wizard of Oz or had the pleasure of

watching Arnold Schwarznegger do his work in The Terminator, may understand the

words, but will be left agog as to what's being said. It is true that a huge load of

commonplaces consists of allusions, some of which can take on a life of their own and

become intelligible to people who've learned them independently of any familiarity with

their origins. Consider "I think that's a Micky Mouse idea." If the time ever comes when

kids don't grow up on this part of the Disney fare, chances are that this will still survive,

at least for a while, as a sensical idiom for a lot of Americans, and maybe even

Englishfolk and English-speaking Bangladeshis. But in general, allusions depend for

their force on a common domain of reference.

This is sort of like playing tennis against a backboard with someone else: you bounce the

ball off the board out away from you, and your partner (or opponent) "picks it up" and

returns it. You are "playing to" the backboard by bouncing something off of it in such a

way that it comes back into the playing area bringing with it a novel angle or "spin." (In

fact, the Latin term "alludire," compounded of ad [to] and ludire [to play], means "to

play to," and by extension, "to play off of.")

Sometimes we resort to allusions as a sort of code that is meant to exclude some from

understanding at the same time it cuts others in. This isn't always snobbery. Parents may

want to share thoughts with each other in front of their children that they don't

particularly want the kids to pick up on, and (unless they share a second language the

children don't) allusion often offers a way through the minefield. But often allusion can

do powerful work beyond this sort of communication-under-censorship. Writer's can use

allusion to invite readers to import a rich body of already-established connotation into the

context of some scene they are presenting to our imagination. And, historically in

European literature since the Middle Ages, the most prominent source of allusions has

been the Old and New Testaments and, beyond these, to a famous body of religious

literature (ranging from sermons to religious allegories).

Even a writer like Ernest Hemingway, who would surely qualify as an unbeliever in

religion, was fond of allusions to the Bible. The title of the novel The Sun Also Rises

comes from the King James Version (1611) of the Old Testament Book of Ecclesiastes,

which expresses the weary despair at the spectacle of the world's processes imagined as

endlessly repeating without any transcendent purpose (the sun rising, and going down;

the monotonous circuits of the winds, generations following generations, etc.) Much

later in that book, the voice of "the Preacher" asks, "What gain has the worker from his

toil?" The reader who is aware that this book of the Bible is often seen as a compilation

of two very different texts -- one by a weary skeptic and another, supplied as a frame to

it, by a fervent believer determined to convert the skeptic's utterance to pious purposes -is set to appreciate Hemingway's choice of phrase, and to follow the prompting which

this framing provides for the story that the author attaches to it, which turns out to be a

powerful expression of the disillusionment that settled upon many, including Hemingway

himself, in the wake of The Great War.

After the Bible, as a source of allusion in European (including English) literature, comes

Greek and Roman mythology -- at least until recently. When Alexander Pope illustrates

the way sound can reinforce sense in skillful verse, one of the couplets he deploys is

When Ajax strives some rock's vast weight to throw,

The line, too, labors, and the words move slow.

We are expected to recognize Ajax as the lumbering giant among the Greek

warriors at Troy. It takes an effort for us to push our way through these lines

because practically every syllable is accented. This is not the modern scouring

powder that takes its name from him -- also in view of his legendary strength, but

oddly transformed by the advertising jingle cooked up in (I believe) the 50s, into a

kind of bouncy little washerwoman:

Ajax! -- Boom, boom! -the foaming cleanser

da-da-da-da dah dah

sweeps the dirt

right down the drain!

da-da-da-da-da da

Sometimes allusions are used to call to the reader's mind whole (other) stories,

with their own themes. The point of doing this is to pose 2 questions: Do we

have to do here with parallel situations (the situation alluded to functioning as a

metaphor for the story from within which it is being called up)? Or do we have to

do with contrasting situations (so that the situation being alluded to functions

ironically, i.e., as a foil to the situation it is being invoked to clarify? Either way,

it can alert us to notice aspects built into the present story that we might otherwise

be inclined to overlook, or to overlook the significance of.

Suppose, for example, that in a story in which a mother had to decide to which of

two daughters to give the family quilts. If some language of the story (or even

just the situation itself) invited us to call to mind the story of Solomon's deciding

(1 Kings 3:16-28) the case of the two women disputing over the child, we would

be moved to ask whether we are to notice that the mother decides wisely and

justly (in the manner of Solomon) or stupidly and unfairly (in light of the standard

set by Solomon).

Perhaps the most famous instance in 20th-century literature is James Joyce's

monumental novel Ulysses, which is constructed around an elaborate parallel with

the Homeric epic, the Odyssey. The search of Odysseus's son Telemachus for his

lost father, and the struggles of Odysseus (in Roman legend his name is Ulysses)

to return home after a 20-year absence (10 at the Trojan War, and 10 since his

being shipwrecked on the way home for having incurred the enmity of the seagod Poseidon), form a huge backdrop for one day in modern Dublin, Ireland, in

the life of the young writer Stephen Dedalus and an older Jewish man Leopold

Bloom (who also gets repeatedly compared to the legendary figure of the

Wandering Jew). The parallel works both ways: to emphasize the diminishment

of modern life in comparison with the epic world at the "beginnings" of (Western)

European civilization, and to suggest the hidden possibilities of heroism that are

often obscured by the drab appearances of contemporary existence.

The name Dedalus itself incorporates an allusion to the mythological story of the

architect who designed a famous labyrinth for imprisoning the monstrous Minotaur. The

king who commissioned this ingenious construction, fearing that Dedalus might put his

talents to work for his enemies, has him thrown into the labyrinth, along with his son

Icarus. Dedalus conceives the stratagem of fashioning wings from the feathers of birds

he lures and kills, and manages to leave the labyrinth by flying above it, rather than

wandering within it. This becomes a figure for the autobiographical hero of Joyce's

novel, an engineer (artist) who transcends the morass of contemporary Ireland by rising

above it, to capture it in an impersonal art. (More can be said about what Joyce is up to

here, but this will suffice for present purposes.)