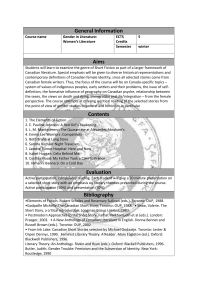

Culture and Identity: Ideas and Overviews

advertisement