United States District Court,D - National Association of Criminal

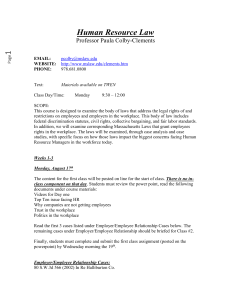

advertisement