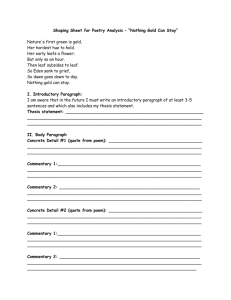

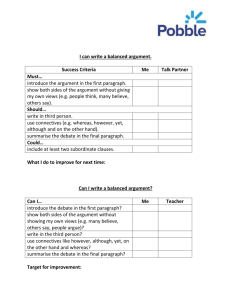

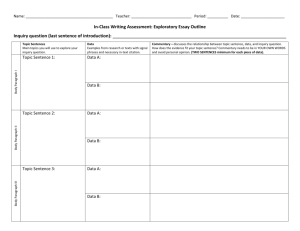

Writers Workshop Unit of Study 8th Grade – Argument Paragraph

advertisement