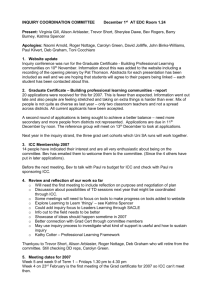

icc-potentialresidua.. - International Criminal Law Services

advertisement