literature in english 8810/01 literature in english 9725

advertisement

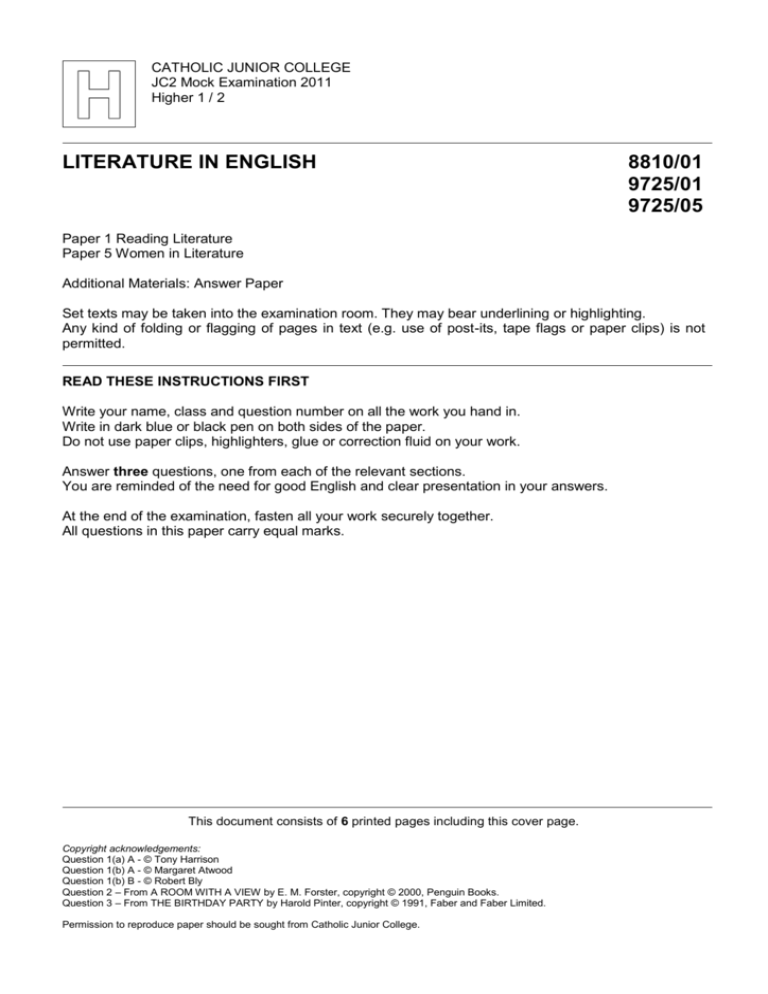

CATHOLIC JUNIOR COLLEGE JC2 Mock Examination 2011 Higher 1 / 2 LITERATURE IN ENGLISH LITERATURE IN ENGLISH LITERATURE IN ENGLISH 8810/01 9725/01 9725/05 Paper 1 Reading Literature Paper 5 Women in Literature Additional Materials: Answer Paper Set texts may be taken into the examination room. They may bear underlining or highlighting. Any kind of folding or flagging of pages in text (e.g. use of post-its, tape flags or paper clips) is not permitted. READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST Write your name, class and question number on all the work you hand in. Write in dark blue or black pen on both sides of the paper. Do not use paper clips, highlighters, glue or correction fluid on your work. Answer three questions, one from each of the relevant sections. You are reminded of the need for good English and clear presentation in your answers. At the end of the examination, fasten all your work securely together. All questions in this paper carry equal marks. This document consists of 6 printed pages including this cover page. Copyright acknowledgements: Question 1(a) A - © Tony Harrison Question 1(b) A - © Margaret Atwood Question 1(b) B - © Robert Bly Question 2 – From A ROOM WITH A VIEW by E. M. Forster, copyright © 2000, Penguin Books. Question 3 – From THE BIRTHDAY PARTY by Harold Pinter, copyright © 1991, Faber and Faber Limited. Permission to reproduce paper should be sought from Catholic Junior College. 2 Section A 1 Either (a) Compare and contrast the following poems, ‘The Word Plum’ by Helen Chasin and ‘Blackberry-Eating’ by Galway Kinnell, considering how your responses are shaped by the writers’ language, style and form. A The Word Plum The word plum is delicious pout and push, luxury of self-love, and savoring murmur full in the mouth and falling Like fruit 5 taut skin pierced, bitten, provoked into juice, and tart flesh question and reply, lip and tongue of pleasure. B Blackberry-Eating I love to go out in late September among the fat, overripe, icy, black blackberries to eat blackberries for breakfast, the stalks very prickly, a penalty they earn for knowing the black art of blackberry-making; and as I stand among them lifting the stalks to my mouth, the ripest berries fall almost unbidden to my tongue, as words sometimes do, certain peculiar words like strengths or squinched, many-lettered, one-syllabled lumps, which I squeeze, squinch open, and splurge well in the silent, startled, icy, black language of blackberry-eating in late September. © CJC 2011 10 5 10 3 OR (b) Compare and contrast the following poems, ‘The Tropics of New York’ by Claude McKay and ‘Island Man’ by Grace Nichols, considering the ways in which the writers’ language, style and form present nostalgia. A The Tropics of New York Bananas ripe and green, and ginger root, Cocoa in pods and alligator pears, And tangerines and mangoes and grape fruit, Fit for the highest prize at parish fairs, Set in the window, bringing memories of fruit-trees laden by low-singing rills, And dewy dawns, and mystical skies In benediction over nun-like hills. My eyes grow dim, and I could no more gaze; A wave of longing through my body swept, And, hungry for the old, familiar ways I turned aside and bowed my head and wept. B 10 Island Man (for a Caribbean island man in London who still wakes up to the sound of the sea) Morning and island man wakes up to the sound of blue surf in his head the steady breaking and wombing wild seabirds and fishermen pushing out to sea the sun surfacing defiantly from the east of his small emerald island he always comes back groggily groggily Comes back to sands of a grey metallic soar to surge of wheels to dull North Circular roar muffling muffling his crumpled pillow waves island man heaves himself Another London day © CJC 2011 5 5 10 15 4 Section B E. M. FORSTER: A Room with a View 2 Either (a) Discuss the role and presentation of Mr. Beebe in the novel. Or (b) Write a critical appreciation of the following passage, making clear its significance in your reading of the novel. But Lucy had developed since the spring. That is to say, she was now better able to stifle the emotions of which the conventions and the world disapprove. Though the danger was greater, she was not shaken by deep sobs. She said to Cecil, ‘I am not coming in to tea—tell mother—I must write some letters,’ and went up to her room. Then she prepared for action. Love felt and returned, love which our bodies exact and our hearts have transfigured, love which is the most real thing that we shall ever meet, reappeared now as the world's enemy, and she must stifle it. She sent for Miss Bartlett. The contest lay not between love and duty. Perhaps there never is such a contest. It lay between the real and the pretended, and Lucy's first aim was to defeat herself. As her brain clouded over, as the memory of the views grew dim and the words of the book died away, she returned to her old shibboleth of nerves. She ‘conquered her breakdown.’ Tampering with the truth, she forgot that the truth had ever been. Remembering that she was engaged to Cecil, she compelled herself to confused remembrances of George; he was nothing to her; he never had been anything; he had behaved abominably; she had never encouraged him. The armour of falsehood is subtly wrought out of darkness, and hides a man not only from others, but from his own soul. In a few moments Lucy was equipped for battle. ‘Something too awful has happened,’ she began, as soon as her cousin arrived. ‘Do you know anything about Miss Lavish's novel?’ Miss Bartlett looked surprised, and said that she had not read the book, nor known that it was published; Eleanor was a reticent woman at heart. ‘There is a scene in it. The hero and heroine make love. Do you know about that?’ ‘Dear—?’ ‘Do you know about it, please?’ she repeated. ‘They are on a hillside, and Florence is in the distance.’ ‘My good Lucia, I am all at sea. I know nothing about it whatever.’ ‘There are violets. I cannot believe it is a coincidence. Charlotte, Charlotte, how could you have told her? I have thought before speaking; it must be you.’ ‘Told her what?’ she asked, with growing agitation. ‘About that dreadful afternoon in February.’ Miss Bartlett was genuinely moved. ‘Oh, Lucy, dearest girl—she hasn't put that in her book?’ Lucy nodded. (Chapter XVI) © CJC 2011 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 5 Section C HAROLD PINTER: The Birthday Party 3 Either (a) ‘The play presents a nightmarish vision of the individual’s existence.’ How far do you find this a helpful comment in your reading of the play? Or (b) Write a critical appreciation of the following passage, relating it to the dramatic presentation of Goldberg and McCann here and elsewhere in the play. McCann. Goldberg. McCann. Goldberg. McCann. Goldberg. McCann. Goldberg. McCann. Goldberg. McCann. Goldberg McCann. Goldberg. McCann. Goldberg. McCann. Goldberg. McCann. Goldberg. McCann. Is this it? This is it. Are you sure? Sure I’m sure. [Pause.] What now? Don’t worry yourself, McCann. Take a seat. What about you? What about me? Are you going to take a seat? We’ll both take a seat. (McCann puts down the suitcase and sits at the table, left) Sit back, McCann. Relax. What’s the matter with you? I bring you down for a few days to the seaside. Take a holiday. Do yourself a favour. Learn to relax, McCann, or you’ll never get anywhere. Ah sure, I do try, Nat. (sitting at the table, right). The secret is breathing. Take my tip. It’s a well-known fact. Breathe in, breathe out, take a chance, let yourself go, what can you lose? Look at me. When I was an apprentice yet, McCann, every second Friday of the month my Uncle Barney used to take me to the seaside, regular as clockwork. Brighton, Canvey Island, Rottingdean – Uncle Barney wasn’t particular. After lunch on Shabbuss we’d go and sit in a couple of deck chairs – you know, the ones with canopies – we’d have a little paddle, we’d watch the tide coming in, going out, the sun coming down – golden days, believe me, McCann. (Reminiscent.) Uncle Barney. Of course, he was an impeccable dresser. One of the old school. He had a house just outside Basingstoke at the time. Respected by the whole community. Culture? Don’t talk to me about culture. He was an all-round man, what do you mean? He was a cosmopolitan. Hey, Nat… (reflectively) Yes. One of the old school. Nat. How do we know this is the right house? What? How do we know this is the right house? What makes you think it’s the wrong house? I didn’t see a number on the gate. I wasn’t looking for a number. No? (Act 1) © CJC 2011 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 6 Section B Answer one question in this section, using two texts that you have studied. The texts used in this section cannot be used in Section C. 2 Either (a) 'I see a woman may be made a fool If she had not a spirit to resist.' (William Shakespeare, The Taming of the Shrew) With detailed reference to any two of the texts you have studied, compare ways in which they explore the idea of the necessity for women to stand up for themselves. Or (b) With detailed reference to any two of the texts you have studied, compare how silence reflects the oppression of women. Section C THOMAS HARDY: Tess of the D’Urbervilles 6 Either (a) Discuss the use of imagery and symbolism in Hardy’s presentation of women in the novel. Or (b) Discuss the role and the significance of religion and the church in the presentation of Tess's experiences in the novel. © CJC 2011