Spencer_Paper_FINAL2.doc - Black Alliance for Educational Options

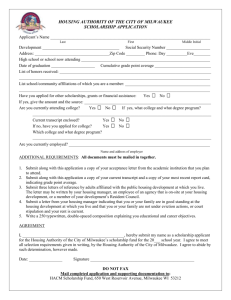

advertisement

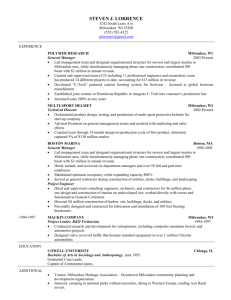

The Struggle Continues Howard Fuller, Ph.D. August 2007 About the Author Dr. Howard Fuller is Director and Founder of the Institute for the Transformation of Learning at Marquette University, where he is a Distinguished Professor of Education. He is a former Superintendent of the Milwaukee Public Schools. He chairs the Board of Directors of the Black Alliance for Educational Options (BAEO), which he and others founded in 1999. Dr. Fuller received his Bachelor's Degree in Sociology from Carroll College in 1962, his Master's Degree in Social Administration from Western Reserve University in 1964, and his Doctorate in Sociological Foundations of Education from Marquette University in 1986. His positions prior to serving as MPS Superintendent (1991-1995) included: Director of the Milwaukee County Department of Health and Human Services, 1988-91; Dean of General Education at the Milwaukee Area Technical College, 1986-1988; Secretary of the Wisconsin Department of Employment Relations, 1983-1986; and Associate Director of the Educational Opportunity Program at Marquette University, 1979-1983. He was also a Senior Fellow with the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University from 1995-1997. 115 “The drums of Africa still beat in my heart. They will not let me rest while there is a single Negro boy or girl without a chance to prove his worth.” Mary McLeod Bethune Introduction1 The effort to expand parent choice is for many a pariah in the continuing debate about how to reform education in America. Conventional wisdom considers the call for parent choice a relatively recent development in America’s long education history. For example, some observers credit a 1955 essay (“The Role of Government in Education” by Milton Friedman) for introducing the concept of empowering parents through government funding to choose what they perceive to be the best educational option for their children. For African Americans, however, the quest for more parent choice goes back much further. Coming out of slavery with a strong belief in the value of education, Black people were forced to seek out both public and private alternatives in their quest. It was then, and it is now, all about options. The lessons of our history teach us that we cannot and must not depend on any one strategy to achieve the goal of educating our young. This history is not well understood. Indeed, for many citizens the phrase “parent choice” is merely another entry on a list of possible education policies. My goal in this essay is to place the discussion of parent choice in a more powerful — and historically accurate — perspective. Understanding this history addresses directly the contention by some that African American support for such policies is misguided at best and the result of being duped by the “right wing” at worst. Why is our history not well understood? In part it is because many actors in the world of education policy willfully have obscured and distorted it. An honest portrayal complicates their effort to curtail the expansion of educational options for African Americans (and other parents). It is also true that many critics of choice might understand this history and simply have come to a different conclusion about its implications. My focus, however, in this essay is on those individuals and organizations that either ignore our history or consciously misrepresent it. They thus impede the continuing struggle of African American people to obtain a quality education for our children. These opponents have placed one obstacle after another in the path of parents who seek the power to choose the best educational The impetus for this essay was a presentation delivered at a conference (“Values and Evidence in Education Reform”) sponsored by the Spencer Foundation in October 2006. 1 215 environment for their children. While cloaking their arguments in the rhetoric of democracy, equity, and social justice, they are in fact this generation’s power brokers and are unwilling to give Black people, particularly low income and working class people, the power they need to determine their own destiny. Daralis Cross On June 10 2007, as Milwaukee’s CEO Leadership Academy (CEO) honored its first high school graduating class, ten young men and women walked across the stage to receive diplomas.2 When it was Daralis Cross’s turn, she had these words for her mother: I give special thanks to you momma. Through everything I’ve been through, you have been there for me, no matter what. There might have been times when you may have felt like giving up on me. But because you didn’t and stood by my side I thank you. I thank you for walking down this long path with me and making sure I never gave up on myself. I also thank you for letting me know that without an open mind and accepting education I would never make it anywhere. And because of you I’m on my way to college to become a whole new person. Thank you. I love you. These powerful sentiments, and those of the other graduates, marked an emotional ceremony. I have been active in the planning and operation of CEO since its inception. I can say with confidence that several members of the Class of 2007 likely would not have graduated but for their attendance at the school. The fact that many now are headed for college would have been implausible a few short years ago. The Milwaukee Parent choice Program (MPCP) is a major reason that Daralis and her classmates arrived at this important stage. Without the MPCP, they would not have been able to attend the CEO. In fact, without the MPCP the school itself would not exist. This program has helped make Daralis, her classmates, and their parents notable exceptions in urban America. First, in our nation’s largest cities the majority of African American students do not graduate from high school.3 The implications of that are staggering. The failure to pass that basic education threshold closes promising doors and opens dangerous ones. 2 CEO (Clergy for Educational Options) is a three-year old private Christian school that enrolled 172 students in grades 9-12_last year. Most students attended the school using educational vouchers through the Milwaukee Parent choice Program (MPCP). CEO has a waiting list of 100 students for 2007-08. “High School Graduation Rates in the United States,” Jay Greene, Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, April 2002 (Revised); “Public High School Graduation Rates in the United States,” Greene and Marcus A. Winters, Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, November 2002; “Public Education & Black Male Students: The 2006 State Report 3 315 Second, most African American parents have limited options in deciding where their children go to school. In Milwaukee, however, initiatives such as the MPCP give parents a wide range of choices.4 The opponents of choice Why aren’t there more programs like the MPCP? This question is especially pertinent given evidence that the expansion of parental education options benefits African American students.5 The scarcity of parent choice in urban America is no accident. That is so because politically powerful organizations actively oppose the kind of programs that give Daralis’ mother — and other parents like her — the power to choose where her daughter attended school. In the tortured view of these opponents, it is not in the “public interest” to allow such a program to exist. Opponents of giving parents more options use lofty terms in their search for the moral high ground on this issue.6 The nation’s largest teacher union, the National Education Association (NEA), says the use of vouchers to expand parental education options will “encourage economic, racial, ethnic, and religious stratification in our society.” This “elitist strategy,” says the NEA, is aimed at “subsidizing tuition for students in private schools, not expanding opportunities for low-income children.” Further, it claims programs such as the MPCP are “a means of circumventing the Constitutional prohibitions against subsidizing religious practice and instruction.” The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) says parent choice “leaves out the rest of the American public — the majority of whom do not have school-age children — who would foot the bill but who would have no way of knowing how their tax dollars are being used…” While the AFT “supports parents' right to send Card,” The Schott Foundation for Public Education; and “Leaving Boys Behind: Public High School Graduation Rates,” Greene and Winters, Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, April 2006. 4 In 2006-07 one in four of Milwaukee’s 130,000 K-12 students used education options unavailable in 1990. See “Parent choice: Doing It The Right Way Makes A Difference,” National Working Commission on Choice in K-12 Education, Brookings Institution, 2003; “Survey of Parent choice Research,” Gerard Robinson, Institute for the Transformation of Learning, Marquette University, Spring 2005; The Education Gap: Vouchers and Urban Schools, William Howell and Paul Peterson, The Brookings Institution, 2006; and Parent choice — The Findings, Herbert Walberg, The Cato Institute, 2007 5 6 See discussions of educational vouchers at www.nea.org and www.aft.org. 415 their children to private or religious schools [it] opposes the use of public funds to do so. [This] is because public funding of private or religious education transfers precious tax dollars from public schools, which are free and open to all children, accountable to parents and taxpayers alike, and essential to our democracy…” Such propaganda reflects a cynical, poll-driven strategy to define parent choice in negative terms, i.e., divisive, untested, elitist, undemocratic, and unconstitutional. In truth, however, the power to make educational choices is widespread, long-standing, and highly valued — by those who have it. As Richard Elmore and Bruce Fuller explained more than a decade ago: “Choice is everywhere in American education. It is manifest in the residential choices made by families [and] in the housing prices found in neighborhoods [and] when families, sometimes at great financial sacrifice, decide to send their children to private schools…. [I]n all instances, these choices…are strongly shaped by the wealth, ethnicity, and social status of parents and their neighborhoods.”7 Jeffrey Henig and Stephen Sugarman also describe the “very considerable degree to which families already select the schools their children attend…. [B]y one plausible way of counting, more than half of American families now exercise parent choice [and] some families have more choice than others.”8 In other words, for most Americans parent choice is widespread. Those with limited options are working class and low-income families in urban centers. African Americans and other minority group members constitute a disproportionate share of this population. The effort of opponents to label parent choice as “elitist” is thus laughable and an insult to these citizens. Opposition to parent choice is not confined to teachers’ unions. Within the Black community itself there is a range of opinion. This is as it should be. Not all Black people will or should be expected to have the same views on such an important issue. However, it is critical that the discussion not rely on inaccurate information about the origins of the struggle for parent choice in the African American community. Nor should the objectives of the school choice movement be misunderstood or misrepresented. We must appreciate its place in the continuing struggle to ensure that ALL of our young people get the education they need and deserve. 7 Who Chooses? Who Loses? Culture, Institutions, and the Unequal Effects of Parent choice, Teachers College Press, Columbia University, 1996. “The Nature and Extent of Parent choice,” in Parent choice and Social Controversy, Politics, Policy and Law, Sugarman and Kemerer, eds. The Brookings Institution Press, 1999. 8 515 What drives the opposition? For the most organized and powerful opponents — led by the teachers’ unions — the concern is loss of power. More specifically, it is about controlling the flow and distribution of money. The NEA, AFT, and their allies aim to preserve their sizeable share of the $558 billion9 K-12 education industry. For them, the key questions are: Who will teach in the schools? Who will build and maintain the schools? Who will sell the textbooks? Who will get the research grants? The economics of choice is also an issue for some African Americans. The reality of Black America is driven not only by race, but also by class. Many Black people have a financial stake in maintaining the traditional educational system. In discussing economic issues related to school reform in Atlanta, Detroit, Washington D.C., and Baltimore, Henig made the following observation: Black community leaders are especially leery of any proposed reforms that seem to undercut the financial stability of Black professionals employed by the school system…The bonds that link minority teachers and administrators to the larger African American community have been forged by shared experiences, expectations, and concerns. In addition to these powerful psychological links, there is a broad sense within much of the African American community that Black educators (and other local public employees) play a critical role in the economic health of the local community. Thus reforms that threaten existing educational institutions are seen as carrying real risk to the community.10 At its root, then, the contemporary parent choice debate pits low income and working class parents against the economic interests of more powerful and established adversaries both inside and outside of the Black community. Historical context11 All slave states had a slave code. At the heart of every code was the requirement that slaves submit to their masters and respect all white men. For example, the Louisiana Code of 1806 proclaimed: The condition of the slave being merely a passive one, his subordination to his master and all who represent him…he owes to his master and to all his family, a 9 Digest of Education Statistics: 2006, National Center for Education Statistics. 10 The Color of School Reform: Race, Politics, and the Challenge of Urban Education, Henig.; Richard Hula, Marion Orr, Desiree Pedescleaux. Princeton University Press, 2001. This essay’s focus before 1900 is on the educational experience of Black people in the South. While African Americans also lived in northern states, they constituted a very small proportion of the Black population. 11 615 respect without bounds, and an absolute obedience and he is consequently to execute all of the orders he receives from his said master, or from them. These codes sought to do more than just teach slaves to be obedient. They were, in fact, also aimed at developing within slaves a fear of all white men. As Kenneth Stampp explains in the title of the fourth chapter of The Peculiar Institution, the aim was to “Make Them Stand in Fear.” Specific codes denied people of color access to education in any form. For example, the South Carolina Act of 1740 provided, “Whereas, the having slaves taught to write, may be attended with great inconveniences: Be it enacted, that all and every person and persons whatsoever, who shall hereafter teach or cause any slaves to be taught to write, or shall employ a slave as a scribe in any manner of writing whatsoever, every person or persons shall for every offense forfeit the sum of one-hundred pounds, current money.” The City of Savannah, in 1818, announced: “The city has passed an ordinance by which: any person that teaches any person of color, slave or free, to read or write, or causes such person to be taught, is subjected to a fine of $30 for each offense; and every person of color who shall keep a school to teach reading or writing is subject to a fine of $30, or to be imprisoned ten days and whipped thirty-nine lashes.” Despite the persistent and ever-present oppression of slavery, and notwithstanding the explicit ban on education, Black people developed and sustained a belief in the critical necessity of obtaining an education. As Jim Anderson explains: “There developed in [the] slave community a fundamental belief in learning and self-improvement and a shared belief in universal education as a necessary basis for freedom and citizenship.”12 He describes the historic and powerful legacy of this belief: As the masters increased efforts to stifle the slaves’ desire for literacy, the slaves seemed more convinced that education was fundamentally linked to freedom and dignity. This distinctive orientation toward learning was transmitted over time…In the history of Black education the political significance of slave literacy reaches beyond the antebellum period. Many leaders and educators [after the Civil War] were men and women who first became literate under slavery...slaves who had sustained their own learning process in defiance of the slave-owners’ authority. As an outgrowth of this history, newly freed slaves — armed with their belief in education — demanded free universal education. Anderson writes that ex-slaves “viewed 12 The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860-1935, James D. Anderson, University of North Carolina Press, 1988. 715 literacy and formal education as means to liberation and self-determination.” But that outlook was at odds with the prevailing view of many whites in the South and North. Explains Anderson: “Blacks soon made it apparent that they were committed to training their young for futures that [assumed] full equality and autonomy. Consequently, the assumption [by many whites] that Blacks had no ideas about the meaning and purpose of education in a free society was quickly replaced with the belief that they held the wrong ideas about how and for what purpose they should be educated.” Important elements of this history are not well understood. For example, it was the demands of Black people that eventually led to the creation of public schools in the South. This occurred as part of an on-going battle not only about the nature of Black education but also about whether Blacks should be educated at all. Because of the push by Blacks during Reconstruction, educational opportunities expanded for Blacks and poor whites as well. As Heather Andrea Williams explains: African American insistence on establishing schools transformed education throughout the southern states. Absurd as it may have first appeared to many white southerners…the sight of Black children in school became an inescapable fact. In the decade of the 1860s, freedpeople attended schools by the thousands. They rebuilt burned-out schoolhouses, armed themselves to protect threatened teachers, and persisted in the effort to become literate, self-sufficient participants in the larger American society. …Following freedpeople’s example, poor whites in the South began attending school and northern missionaries and state legislatures took action to establish educational facilities for large numbers of poor whites who had previously gone unschooled.13 After Reconstruction, considerable power in the South returned to the whites who had dominated prior to the Civil War. A clear manifestation of that can be found in the Compromise of 1877. As Anderson explains: Southerners agreed to the election of Rutherford B. Hayes and Republicans agreed to remove Federal troops from the South. With both state authority and extralegal means of control firmly in their hands, the planters, though unable to eradicate earlier gains [by Blacks], kept universal schooling underdeveloped. They stressed low taxation, opposed compulsory school attendance laws, blocked the passage of new laws that would strengthen the educational basis of public education, and generally discouraged the expansion of public school opportunities. Eventually white small farmers led the battle for universal public education for their children. To accommodate this demand the whites in power began to take money from the Black public schools and give it to white public schools. Black people were then put between a “rock and a hard place.” They were forced to pay 13 Self-Taught: African American Education in Slavery and Freedom, Andrea Williams, University of North Carolina Press, 2005. 815 taxes for schools that they were not allowed to attend and as a result they had to use their meager resources to support both public and private schools for their children. They were victims of double taxation. A 1911 study by W.E.B. Du Bois and Augustus Dill reinforces this history. 14 As summarized in proceedings of the 16th Annual Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems, the study found that: [A]ppropriations for Negro schools have been cut… [W]ages for Negro teachers have been lowered and often poorer teachers have been preferred to better ones. Superintendents have neglected to supervise the Negro schools. [F]ew school houses have been built and few repairs have been made; for the most part the Negroes themselves have purchased school sites, school houses, and school furniture, thus being in a peculiar way double taxed. Negroes in the South, except those of one or two states, have been deprived of almost all voice or influence in the government of the public schools. Those presiding over the conference said that “as a result of such conditions it is certain that of the Negro children six to fourteen years of age not 50 per cent have a chance today to learn to read and write and cipher correctly. Unless we face these facts the problem of ignorance…will soon overshadow all other problems.” Black people thus were forced to seek out and develop other options to ensure education for their children. The conference report described those efforts as follows: The Negroes themselves are making heroic efforts to remedy these evils [through] and widespread system of private, self-supported schools…[P]hilanthropy is furnishing a helpful but incomplete system of industrial, normal, and collegiate training for children of the Black race. The continuing struggle for Black education took on new meaning, new definitions, and new directions after the 1954 Supreme Court decision on desegregation. “The Common School and the Negro American,” Du Bois and Dill, Atlanta University Publications, No. 16, Atlanta University Press, 1911. 14 915 Brown v. Board of Education Observers justifiably viewed the Supreme Court’s decision as a watershed event. In the words of Martin Luther King Jr., "For all men of good will May 17, 1954 came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of enforced segregation . . .It served to transform the fatigue of despair into the buoyancy of hope."15 Three years ago, on the fiftieth anniversary of Brown, a wave of conferences examined its impact. Numerous books and articles supplemented the many papers presented at these gatherings. A summary of one conference described a prominent theme: “[Fifty] years after Brown …the unfortunate fact remains that too many African Americans remain far behind on tests of achievement, creating a Black-white test score gap…about as large and persistent as it was when first measured in the late sixties.”16 In other words, notwithstanding the historic significance of Brown, educational gains that many hoped for have not materialized. While there is no single reason, I argue that a key factor involves the way Brown was implemented in many American cities. Specifically, consistent with the longstanding experience of Black people before Brown, African Americans generally did not control the public policies and practices developed to implement the decision. As had been the case historically, key decision affecting the education of their children often remained beyond their reach. Milwaukee’s story vividly illustrates the gap between the spirit of Brown and the manner in which the decision was implemented. 17 It is described in some detail here. In 1976, twenty-two years after Brown, Federal Judge John Reynolds declared the Milwaukee Public Schools (MPS) to be unlawfully segregated. Reynolds named John Gronouski, a former ambassador to Poland and a longtime political associate, to develop a plan for ending segregation. Gronouski worked closely with then-MPS Superintendent Lee McMurrin and his top deputy, David Bennett. 15 From a 1960 speech to the National Urban League. 50 Years after Brown: What Has Been Accomplished and What Remains to Be Done?” April 22-24, 2004, Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University 16 17 Sources for this description of the Milwaukee integration experience include: (1) "The Impact of the Milwaukee Public Schools System's Desegregation Plan on Black Students and the Black Community (1976-1982)," Howard Fuller, doctoral thesis, Marquette University, 1985; (2) “Better Public Schools, Final Report,” Study Commission on the Quality of Education in Metropolitan Milwaukee Public Schools, Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction, 1985; (3) "School Desegregation Ten Years Later — Why It Failed," Bruce Murphy, Milwaukee Magazine, September 1986; and (4) "An Evaluation of State-Financed School Integration in Metropolitan Milwaukee," Error! Bookmark not defined., Wisconsin Policy Research Institute report, 1989. 1015 The news media and most members of Milwaukee’s civic establishment strongly supported the resulting plan. It relied on (1) a system of “magnet” schools to attract white students to the central city and (2) a large-scale busing program that transported African American students to schools in predominantly white neighborhoods. A vocal but relatively powerless group of African Americans complained that the plan had been developed with minimal input from African American families. They claimed it would place a disproportionate burden on African American students, supposedly the main beneficiaries of the Reynolds decision. The news media and established community leaders stereotyped these critics in negative racial terms. Judge Reynolds sanctioned the plan and MPS began implementation in the late 1970s. By the mid-80s, most MPS schools were racially desegregated. Milwaukee's political and civic leaders congratulated themselves. The media celebrated the "peacefulness" of the process and trumpeted MPS claims that most students were "at or above average" in test scores. Opponents of the plan continued to be marginalized as racists and/or racial separatists. That charge, while true in the case of some plan critics, became a means for summarily dismissing any criticism. By the end of the 1980s, independent research and reporting (see note 17) had validated the early critics of the plan. This research demonstrated that the plan: Gave the best educational choices primarily to middle- and upper-income, mostly white parents; and Uprooted a disproportionate number of African American children and assigned them to distant schools. The research also discredited MPS claims that academic achievement had improved as the integration plan was implemented. After an 18-month study, an independent state task force decried an "unacceptable disparity in educational opportunity and achievement between poor and minority children...and non-poor and white children..." It determined that MPS classified students "at or above average" even if they scored substantially below the 50th percentile. African American test scores were well below the 50th percentile in almost all grades and almost all subjects. By far the most troubling aspect of the Milwaukee plan involves the now-acknowledged motives of those who developed it. Documents relied on at the time of the plan’s development illustrate how priorities were established. An internal MPS document stated, “...[T]he psychological guarantee of not having to attend a school that is predominantly minority will tend to stabilize the population in the city." An education professor at the University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee referred to the "optimum percentage of minority students in a desegregated school.” He said, 1115 emphasis added, "[Fifteen] per cent is a minimum if the minority group is...to exert pressure without constituting a power threat to the majority." Another educator wrote: "[A]s long as the proportion of Black pupils is small...and expected to remain so, there is no reason for white pupils to experience stigma, relative deprivation, social threat, marginality, or a change in norms, standards, or...expectations of their significant others.” Not until 1999 did one of the plan's architects openly acknowledged the inescapable meaning of such sentiments. At a forum on race relations in Milwaukee, a former senior MPS administrator told a startled audience that "white benefit" was a central consideration in the plan's development. When news of this circulated, the result was a page one story (“‘White benefit’ was driving force of busing”) in the October 19, 1999 Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. The article’s sub-headline stated, “Twenty years later, architects of MPS plan admit they didn't want to disrupt city's white residents.” The article began as follows: In a stunning admission more than two decades after the fact, the architects of Milwaukee's school busing plan now say the entire plan was set up for "white benefit" at the expense of African-American children. "I think it was an unspoken issue with the School Board at the time," said Anthony Busalacchi, president of the School Board in 1978-'79. "It was an issue of how do we least disrupt the white community." This was the offensive racial prism through which "equal educational opportunity" for African American children in Milwaukee was pursued. The supposed era of peaceful and voluntary racial integration in fact was a period of forced busing that placed the principal burden on African American children.18 At the same time, reflecting the plan’s specific goals, a larger proportion of white students either stayed in their neighborhood schools or transferred to “magnet” schools, many of which had selective admission practices. Within a decade of the Reynolds decision, there was growing awareness and resentment of its impact among African Americans. Their reaction of many Black people echoed a historic pattern, one that reflected the logical progression of our struggle. As had occurred so often in the 1800’s and earlier in the 1900’s, African Americans were forced once again to seek other options for their children’s education. This included an unsuccessful effort to establish a separate school district, an effort that was successfully 18 The busing pattern in the Auer Avenue School neighborhood was representative of how African American children traveled up to two hours a day to schools outside their neighborhood. In the Auer Avenue neighborhood, 1,071 students — two-thirds of all elementary age children in that area — were transported to 97 different schools in 198788. 1215 resisted by the same individuals who were in charge of implementing the “white benefit” plan. Following that setback, many Blacks in Milwaukee coalesced to support the 1990 enactment of the MPCP. Their logic was straightforward: the traditional system was not working; we were not allowed to form our own district; and so the next obvious step was to demand a way for our children to be educated outside of the traditional public system. As cities developed plans to implement Brown, the fear of “white flight” was not unique to Milwaukee. While individual plans varied from one community to the next, efforts to comply with Brown typically rested on mandatory assignment plans that required long bus rides for a disproportionate number of African American students. As in Milwaukee, in many communities those making the decisions reflected traditional leadership structures. This, in turn, minimized the involvement of African Americans. And to what end? In Milwaukee, as in many other cities, levels of racial segregation are similar to those that existed decades ago. Further, as The New York Times reported earlier this year: With Brown v. Board of Education…integration was the big hope for equal achievement…[Yet] experts of every political persuasion agree that the achievement gap — the disparity between white children and Black children’s educational achievement — is the biggest problem in American education.19 Conclusion Since before the Civil War, Black people have waged a continuing struggle to educate themselves and their children. As Williams explains, “issues of power” dominate the history of this struggle. Time and again, Black parents have been in a position where others had the power to make fundamental decisions about the education of their children. While those in power have employed very different means, the net result has left low-income and working class African Americans with fewer and less adequate educational options. The current debate over parent choice is but the latest chapter in that struggle. This debate arises directly from the fact that far too many of our poorest children are not receiving a quality education. In the starkest of terms, their futures are being snuffed out. A troubling double standard hangs over this debate. Many who can choose quality options for their own children question the idea of empowering less affluent families to do likewise. It is all the more regrettable that some of the most powerful choice opponents describe their stance as reflecting concerns about “equity” and “justice.” “Money, Not Race, Fuels New Push to Buoy Schools,” Tamar Lewin and David M. Herszenhorn, June 30, 2007. 19 1315 There is another aspect to the struggle. Many organizations and individuals in the Black community are either hostile or indifferent to parent choice. Urban school systems historically have employed large numbers of African-Americans, and for most of us the traditional public school has been our only hope for receiving an education. While the traditional system has served many of us well, that was then and this is now. Though today's public school systems still employ us, far to few are effectively educating our children My own vision for the future of our struggle remains anchored by the belief that we must give poor parents the power to choose schools — public or private, non-sectarian or religious —where their children will succeed. As our history illustrates, this is not a new idea. Rather, it goes to the very heart of the historical quest by Black people to educate themselves and their children. We can see in Milwaukee the tangible impact of putting this power in the hands of families who once lacked the resources to influence the decisions that shape their children’s education. The graduation ceremony at CEO Leadership Academy is but one of many illustrations of how this power can change the shape of the future for their children. I am proud of the fact that CEO Leadership Academy is just another example of Black people fighting for an education that will give Daralis and others like her an opportunity to become economically and socially productive citizens in this country and indeed in this world. We stand on the shoulders of our ancestors who fought against slavery, resisted “Jim Crow,” and always kept in mind the struggle for freedom and selfdetermination. Some argue that parent choice serves only a portion of the population, and that we should expend all our resources on a system that – presumably – serves all. I think we should take a lesson from Harriet Tubman’s fight against slavery. She fought everyday to end it, but as she waged that battle, she set out to free as many slaves as possible. I believe we must work hard to improve the traditional public education system in this country, but in the mean time, we have a moral responsibility to rescue as many of children as we can “by any means necessary.” 1415