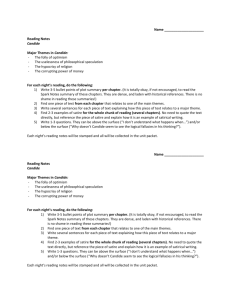

Voltaire_-_Candide.doc

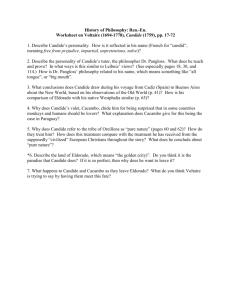

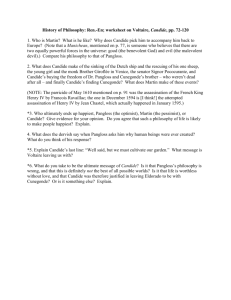

advertisement