The Devil`s Blue Dye: Indigo and Slavery

advertisement

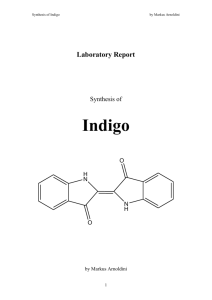

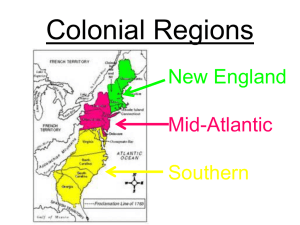

The Devil's Blue Dye: Indigo and Slavery Jean M. West "One hundred thousand slaves, Black or mulatto, work in sugar mills, indigo and cocoa plantations, sacrificing their lives to gratify our newly acquired appetites for sugar, cocoa, coffee, and tobacco--things unknown to our ancestors." --Voltaire, Essay on Morals and Customs, 1756 Blue is as American as, well ... red, white, and blue. Indigo blue bunting is the field for the stars of the Star-Spangled Banner. Almost half the flags of the original thirteen states feature blue backgrounds including Virginia, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and South Carolina (whose 1756 palmetto flag design predates independence.) Mississippi announced its declaration of secession in 1861 by raising a flag over the state capitol featuring a lone star on a blue field; composer Harry McCarthy's tribute to the "Bonnie Blue Flag" made it the unofficial flag of the Confederacy. Blue is not just the color of flags of America. Blue is the color of Levi Strauss' jeans empire. Blue is the color of police uniforms ("the men in blue"), the Army and Marine's "dress blues," Navy Blues, and the Cub Scouts' shirts. Blue is consistently one of the top ranked finishes in DuPont's annual automotive color popularity survey. Blue is even the color of hurricane evacuation signs, as well as the tarps provided by the Army Corps of Engineers through Operation Blue Roof to victims whose roofs are hurricane-damaged. Yet, blue isn't just a hue. Singers belt out "blue songs," from country singer LeAnn Rimes' "Blue," to rocker Linda Ronstadt's "Blue Bayou," and from crooner Bing Crosby's "Blue Skies, to jazz virtuoso Ella Fitzgerald's rendition of Rogers and Hart's "Blue Moon," or Elvis Presley's "Blue Suede Shoes." Of course, one of America's signature sounds is blues music, which became the foundation for jazz, rhythm and blues (R&B), rock and roll, and hip-hop. Many Americans realize that the blues emerged from African-American gospel and work songs, but not as many realize that the color blue is also directly linked to the African-American experience and slavery. The link is a deep blue natural dye, indigo. Indigofera "Visible indigo light has a wavelength of about 445 nm (nanometers)." --NASA, Atmospheric Sciences Data Center True indigo comes from plants belonging to the legume genus Indigofera, a subtropical shrub that grows to be around 4-6 feet tall and whose leaves contain the chemical components necessary to produce a fade-resistant blue dye. The species Indigofera tinctoria, native to Asia, has always been the most valuable indigo species traded. Indigofera arrecta is the most common variety in Africa, but Indigofera tinctoria may be found in Senegal and Indigofera hirsuta in Madagascar. Indigofera hirsuta, now considered a nuisance plant or weed, is native to northern Australia and Africa. Central and South America also have native indigo species, Indigofera suffructicosa and Indigofera arrecta. Temperate climates in many regions of Africa, China and Europe were too cold for Indigofera, so people in these areas extracted blue dyes from other types of plants. West African coastal tribes used blue coloring extracted from Lonchocar pus eyanescens while Polygonum linlorium was used in China. Perhaps most famously, woad (Isatis tinctoria) a plant from the mustard family, was used by the warriors of the British Isles to dye their skin, giving them the name Picts or the "painted" people. Indigo became the "king of dye" early in history. The use of the plant's blue dye for adornment, religious ritual, and as a symbol of political and social status occurred independently in cultures around the world. The central role played by India is captured in the word "indigo." Although the Sanskrit name for the dye came from nila, meaning dark blue (and survives in our word, aniline), the ancient Greeks referred to the product as the Indian dye, indikon. Asian cultures including India, Indonesia, and China have a long tradition of using indigo to print, dye, and batik textiles. Japan developed a heated vat method to dye fabrics and also decorated them using multiple techniques including shibori (tie-dye). India supplied their blue dye to the ancient Middle East and the Greco-Roman world. The oldest evidence of indigo survives with Egyptian mummies from Thebes, dating back 5,000 years. Mesopotamian cuneiform tablets record Assyrian ruler Tiglat-Pileser III seizing blue-dyed wool during conquests 2,700 years ago along with instructions for dyeing cloth lapis-blue. A Persian rug from the 5th century B.C. included indigo-dyed fibers. The Greek writer Herodotus describes the use of indigo in the Mediterranean in his histories written about 450 B.C. Indigo was also used in the Americas long before the arrival of Europeans. The Nahuatl of Guatemala called the native indigo xiuhquilitl (blue herb) and used it to paint murals, pottery and cloth. Inca mummies are wrapped in cloth dyed with indigo. Indigo was also used for eye shadow and as a hair dye in both the Old and New Worlds. Indigo in Parts of Africa "Indigo grows wild in almost every part of the African Coast ... Besides the Indigo, there is another plant which the natives use as a blue dye, which appears to impart a more indelible color, and which, should it stand the test of experiment, might also be cultivated." --British Report of the Committee of the African Institution: West African Produce, 25 March 1808 Some Africans have used indigo for centuries as symbol of wealth and fertility. Indigo-dyed cotton cloth excavated from caves in Mali date to the 11th century and many of the designs are still used by modern West Africans. The Tauregs, "blue men" of the Sahara, are famous for their indigo robes, turbans, and veils that rub blue pigment into their skin. Yoruba dyers of Nigeria produce indigo cloth called adire alesso using both tie-and-dye and resist dye techniques, while honoring Iya Mapo, as the patron god of their exacting craft. Dyers of the Kanuri (Cameroon and Nigeria) and Fulani (modern Niger and Burkina-Faso) ethnic groups popularized indigo near Lake Chad and through portions of West Africa. [Within Africa] dyers are women including among the Yoruba, the Malike and Dogan of Mali, and the Soninke of Senegal. Dyeing is also performed by men among the Mossi (Burkina-Faso) and the Hausa, who have produced indigo-dyed textiles in the ancient city of Kano (Northern Nigeria) since the 15th century. The Devil's Dye All the kings and parliaments that have been or shall be cannot govern our fancies--Two things Among us are too ungovernable, viz, our passions and our fashions." --Daniel Defoe, A Plan of the English Commerce, 1728 Just as we do today, people of the past indulged themselves in new fashions or crazes. The 17 th century was the era when exotic items from the Orient became objects of near mania for Europeans. In 1865, a single tulip bulb cost tons of wheat, rye, beer, butter, oxen and miscellaneous items valued at $35,000 today. Indigo, too, was part of this craze for exotic imports, generating impassioned debate and legislation. In 1498, Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama blazed the sea route to India and opened up direct trade with the subcontinent. In doing so, he made indigo much more accessible to the average European. Prior to that time Arab traders carried indigo-dyed fabrics and the dye itself along caravan routes to trade centers such as Cyprus, Alexandria, and Baghdad, where they were resold to Italian merchants who carried them to Europe. The length and danger of the journey and mark-up by middlemen made indigo extremely expensive. Not everyone was thrilled in the wake of da Gama's voyage at the prospect of lower prices for indigo. Woad had been cultivated extensively in France, Germany, and England since the Roman Empire. Woad-growers and merchants from a number of countries feared competition from indigo since it was a superior dye producing deeper and more colorfast blues. Joining together, the Woadites worked to prevent importation of indigo. They claimed indigo was a dangerous product, would rot yarn, and was the devil's food, drug, color, and dye! During the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, England banned importation of indigo and inspectors burned any contraband indigo they found. France and Germany also prohibited indigo imports in the late 1500s. Dyers had to take an oath that they would not use indigo and could be put to death if they did. Nevertheless, during the expansion of European power into the Far East, Portuguese merchants and the Dutch, French and British East India Companies traded in indigo. By the late 1600s indigo was being legally marketed in most European nations. The "Indigo Craze" exploded as European consumers clamored for indigo-dyed fabrics, paints, and laundry bluing (which made white fabrics appear whiter.) India was hard-pressed to keep up with the demand. European nations also resented the Indian monopoly of the indigo trade. Since indigo could not grow in Europe's climate, European colonial powers turned to their tropical colonies in the New World for a nonIndian indigo source. Colonial Indigo Plantations "Those who make it in America, often maliciously mix it with Sand and Dirt, but the Cheat is easily discovered; as Indigo that is fine and pure will burn like Wax, and, when burnt, the Earth or Sand will remain." --Anonymous author, A Friend to Carolina, 1746 The Spanish first began to grow indigo in the mid-1500s on plantations along the Pacific coast of Central America in modern Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala, eventually extending cultivation to Mexico and Florida. They also established indigo plantations on the island of Hispaniola. The French, upon acquiring the eastern third of the island (St.-Domingue, or modern Haiti) in 1697, developed 3,150 plantations, which yielded 758,628 pounds of indigo by 1790. They also introduce indigo into Louisiana; in 1763, it was the colony's top export. When the Spanish took over Louisiana (1769-1803) indigo continued to be the main cash crop in the area around New Orleans. Worm infestations at the end of the 18th century caused repeated crop failures and by 1800, planters turned to sugar, cotton, and tobacco. Indigo was cultivated throughout the West Indies by other colonial powers including the English in Jamaica, the Danes in the Virgin Islands, and the Dutch in Suriname. The precious dye would be shipped back to Europe on the Gulf Stream trade route. From time to time a cargo would be shipwrecked. El Nuevo Constante, lost in 1766 off the Louisiana coast, carried 2,896 pounds of indigo in 200pound pouches; incredibly, modern archaeologists diving in 1980 found a piece of the dye that had survived underwater for 214 years. Guatemalan and French West Indies indigo became the American standard for excellence, commanding prices twice or three times higher than that produced by other American colonies. Still, no New World indigo producer had the reputation for quality held by India. Slavery on the Indigo Plantation "From fifty to sixty hands work in the indigo factory; and such is the effect of the indigo upon the lungs of the laborers, that they never live over seven years. Every one that runs away, and is caught, is put in the indigo fields, which are hedged all around, so that they cannot escape again." --James Roberts, The Narrative of James Roberts a Soldier under Gen. Washington in the Revolutionary War, 1858 The earliest workers on Spanish indigo plantations were Native Americans who were either enslaved outright or bound to the land like serfs through the feudal-style encomienda system. When the Spanish became convinced that the Indians were dying of diseases caused by indigo processing, they shifted them to field work and began buying African slaves to work the dye vats because they believed black slaves were less susceptible to illness. Although there is no definitive proof that Africans were imported specifically for their knowledge of indigo cultivation and processing, few Europeans had experience cultivating or processing indigo. Because so many slaves had prior experience with indigo in Africa, their skills complimented and supported the indigo economy, certainly helping to make it a profitable business. As slaves worked with the plant and extracted dye, they improved methods. Francis Peyre Porcher described in detail in Resources of the Southern Fields and Forests a "method successfully used by a negro (Geoffrey) on a plantation (Mrs. J. S. P.), St. John's, Berkley, South Carolina, to prepare a dye from the wild indigo." Governor James Glen calculated in A Description of South Carolina (1761), that a single slave could plant and care for two acres of indigo and that each acre could yield 80 pounds of indigo; in that case, with 1761 prices averaging around 3.2 shillings per pound of indigo, each indigo slave generated nearly £13 annually, roughly equivalent to $2,000 today. Indigo cultivation involved manual labor, although the fieldwork was not as intense as for sugar or rice. In the Caribbean, fields could yield up to five cuttings (harvests) per year while in North America, slaves sowed crops in April, made their first cutting in early July, and the (optional) second cutting in late August. In South Carolina and Georgia, slaves in the indigo fields typically worked according to the task system; i.e. they were assigned a specific amount of work to accomplish in a day, rather than being driven by an overseer in a gang. Slaves cleared the indigo fields, ploughed, hoed, and smoothed the ground in preparation for planting; they sowed indigo seed during dry spells (no rain) in rows about 18 inches apart. Young plants are pale yellow and may die if the temperature falls too low for even one day, but after about a week, the plant turns green. Insect pests often attacked the plants at this point, and they were still vulnerable to hard rain or hail. Slaves typically began weeding when the plant was 2-3 inches tall. When the plants reached a foot tall, enslaved workers then plowed between the rows again to add oxygen to the soil. If drought lasted for more than six weeks, the plants would start to blacken and die. When the indigo was 2-5 feet tall and almost ready to flower, the harvest would begin. If more than one "cutting" was planned, the workers would leave sprouts at the bottom of the stem. Field slaves would cut the indigo stalks, bundle plants together by tens into a cart and haul the harvested indigo to a plantation-based processing facility the same day it was cut. Indigo did not require expensive machinery for processing; a 3-stepped set of tubs or vats would process 6-7 acres of indigo plants. Two rows of vats (about 18' by 18' by 3') were constructed of brick and coated with cement, with spigots and drain holes, the first row about 3 feet higher than the second. Each vat held about 100 bundled indigo plants and a thousand cubic feet of water. Teams of ten slaves typically attended vat sets. Less wealthy planters could cultivate the crop with unskilled slaves, but indigo processing required them to purchase slaves with the technical skill to prepare the dye and the stamina to work in a disgusting environment. Slaves placed the cut indigo in the "steeper," a large tub filled with water and sank the plants with logs or stones. In about 12-24 hours, the indigo began to ferment, making the water bubble and turn amber-green as it drew the pigment grain from the leaves. Although the colonial dye-makers described the putrid smell of the rotting indigo, they did not realize that the indigo was oxidizing, forming a liquid chemical now known as indican. The fermented mixture was drawn down into the second "beater" vat where trash was picked out of the liquid and it was churned with paddles by the slaves to add oxygen until it turned green and then violet-blue, around two hours. Continued churning caused the indigo to condense into specks, then flakes, which sank like mud to the bottom of the vat, separating from the now clear water. (The addition of limewater hastened the process, but seems to have precipitated other particles, resulting in an inferior indigo.) Contemporary drawings show that sometimes, slaves stood inside the vat and beat the mixture with poles. The water was drawn into the third container, leaving the indigo at the bottom of the second vat. Slaves spooned the puddingconsistency indigo into cloth bags to drain overnight. The next day, they packed the blue mud into square, brick-size containers with drainage holes. After additional pressing and drying, slaves removed the indigo from the molds and cut it into squares roughly 1½ inches in size. When completely dry, premium pieces of "pigeon neck" indigo were a sparkling, iridescent dark blue, light in weight and very hard. Indigo dye is not water soluble (the reason why it separates in the second vat) so when ready to be used for dying it was dissolved in stale urine, tannic acid, or wood-ash. The stinking mixture would then be introduced into water, producing a yellow-green solution. Cloth dipped into the dye solution turned yellow-green until it was removed from the liquid and exposed to oxygen--then, almost magically, as the cloth would dry, it would turn blue. Slaves who worked in the dye-houses were easy to identify; their hands were stained blue. In 1761, Governor Glen remarked, "...both Indigo and Rice may be managed by the same Persons, for the Labour attending Indigo being over in the Summer Months, those who were employed in it may afterwards manufacture Rice in the ensuing Part of the Year, when it becomes most laborious; and after doing all this, they will have some Time to spare for sawing Lumber and making Hogsheads, and other Staves to supply the Sugar Colonies." A slave, who could manage two acres of indigo, yielding one crop per year, could also manage an acre of rice, yielding one crop a year. As the indigo crop cycle ended (in October), rice beating began. Only about 5 percent of coastal plantations (where rice was also grown) cultivated indigo, compared to 11 percent of backcountry plantations (because indigo was relatively lightweight, cheap to ship, and of high value.) Upcountry slaves typically spent the other half of the year growing food, cutting timber and producing naval stores (tar, pitch and turpentine) from pinesap. Unquestionably, slaves on dual-crop plantations lived hard lives of unceasing labor. Health Issues "The rotting vegetation smelled so hideous that even buzzards refused to frequent the area around an indigo vat." --Robert Austin and Dorothy Moore, Archaeology of the New Smyrna Colony, 1999 There is some debate over whether the organic chemistry involved in indigo processing posed a health threat to slaves. One Louisiana chronicler, echoing African-American Revolutionary soldier James Roberts' narrative, claimed that indigo, "on average killed every Negro employed in its culture in the short pace of five years." Abolitionist Quakers such as John Woolman wore undyed clothing, believing reports that indigo caused nerve damage to slaves who dyed cloth. There is some anecdotal information that women indigo dyers in India suffered sterility. Colonial-era writers also reported that indigo processing polluted streams, killing fish, and produced rust on nearby wheat crops. Natural indigo is a complex organic chemical, but one by-product, "indigo yellow," may increase genetic mutations. Slaves with long-term exposure to the vapors given off during fermentation, oxygenation, and precipitation or who stood immersed in vat liquids may have had increased chances of cancer or tuberculosis due to exposure to indigo yellow. On the other hand, modern indigo farmers in southern Mexico are not afflicted by indigo-related diseases, although they do not produce large commercial quantities of indigo. Many of these modern farmers feed indigo to their pigs. Indigo herbal medicines are safely used by many cultures both externally, to clean wounds and treat ulcers, and internally, to fight bacterial infection. Also, recent demographic studies of slavery on St.-Domingue suggest that slaves on indigo plantations gave birth to more children than their contemporaries on sugar plantations, hinting that life as a slave on an indigo plantation was less perilous than on a sugar plantation (while not necessarily meaning that it was a healthy life.) Clearly fermentation created a hideous odor and, as colonial era writers observed, "repulsed livestock." It is not clear, as asserted in some sources, that the stench attracted disease-carrying insects. Indigo samples catalogued in the British Museum's plant collection note that colonials rubbed indigo juice into horses' harnesses as an herbal insect repellent. The diversion of Carolinian slaves to indigo fields from rice fields (where standing water attracted both malarial Anopheles mosquitoes and the Stegiomyia yellow fever mosquitoes) may have offered the slaves some protection from those deadly diseases. Certainly, the 40 years of the "Indigo Bonanza" in South Carolina correspond to a 40-year decline in malaria deaths and absence of yellow fever epidemics. Whether this is coincidence or due to some property of indigo is yet to be determined by scientists. Eliza Lucas Pinckney "Indigo proved more really beneficial to Carolina than the mines of Mexico or Peru were to Spain.... The source of this great wealth ... was a result of an experiment by a mere girl." --Edward McCrady, historian of colonial South Carolina A determined 16-year-old girl, Eliza Lucas (1722-1793), was responsible for the cultivation of indigo in British North America. When her mother's health failed on the island of Antigua in 1738, her father, Lt. Col. George Lucas, relocated his family to South Carolina where he had purchased three plantations, including one on salty Wapoo creek near Charleston, where rice could not be cultivated. When Lucas was recalled to Antigua to serve as governor, his daughter Eliza took over the management of the household and plantations. Eliza was a well-read young woman educated in England and also an amateur botanist, much like her contemporary George Washington. She experimented with crops on the three plantations, recording her activities in her letterbook. Eliza recalled, "I was very early fond of the vegetable world ... when he [her father] went to the West Indies, he sent me a variety of seeds, among them, indigo." In July 1739, she reported to her father "the pains I had taken to bring Indigo, Ginger, Cotton ... to perfection, and had greater hopes from the Indigo--if I could have the seed earlier the next year from the West India's--than any of ye rest of ye things I had tryd." Eliza's indigo experiment did not go well initially. Frost killed the first crop and worms ate the second one. However the third year, 1742, the indigo crop survived. Eliza had succeeded in improving the hardiness of the French tropical indigo to better resist the storms and periodic frost of temperate South Carolina. Having overcome the hurdle of growing the crop, Eliza tackled the tricky task of processing the indigo. Her father hired a white indigo-maker from Montserrat, Nicholas Cromwell, and sent him to Wapoo. Although Cromwell built the vat, Eliza discovered that he had intentionally spoiled the dye so that the Carolinians would not develop into competitors to Montserrat and "ruin his own country by it." Eliza fired Cromwell, although Cromwell's brother remained at Wapoo and assisted her in producing 17 pounds of dye. Finally, Governor Lucas sent a black indigo-maker who had worked in the French West Indies to Wapoo where he successfully processed Eliza's next crop of indigo into dye. Instead of keeping the secret to herself, Eliza (who had chosen to marry the wealthy, learned Charles Pinckney) used most of her indigo crop of 1744 to make seed, which she then shared with a great number of planters. In 1745-1746, South Carolina exported 5,000 pounds of indigo dye. The South Carolina government was thrilled by Eliza's experiments and Governor James Glen advised the colonial assembly in January of 1748 that, "our success in indigo seems to be certain." Indigo, growing on high, dry ground, complimented the already established rice plantations of the marshes, so South Carolina had two lucrative crops, which turned it one of the wealthiest of the thirteen colonies. Table 1: South Carolina Indigo Exports, 1745-1775 Year Pounds 1745 5,000 1748 134,118 1750 120,030 1754 216,000 1755 193,803 1756 232,100 1757 894,500 1760 475,725 1765 467,725 1770 483,094 1773 794,150 1775 1,107,660 Source: Adapted from Table 26 in William James Hagy, This Happy Land: The Jews of Colonial and Antebellum Charleston (Tuscaloosa, Al.: University of Alabama Press); and Figure 6.11 in Marc Egnal, New World Economies: The Growth of the Thirteen Colonies and Early Canada (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998) Eliza personally managed the marketing and sale of her crop, acting as her own agent when she accompanied her sons to England for their education, although James Crokatt, South Carolina's indigo agent in London after 1749, also energetically promoted Carolina indigo. Moses Lindo, a Jewish export agent, served as surveyor and inspector of indigo (1762-1774) and instituted reforms to insure improved, quality-graded Carolina indigo would fetch a better price in world markets. The "Indigo Bonanza" had begun, a 30-year time period when indigo planters could double their money every three to four years. By 1775, indigo was responsible for over a third of South Carolina's income. On the eve of the American Revolution, South Carolina's planters were exporting 1.1 million pounds of indigo, with a modern value of $30 million. Table 2: South Carolina Indigo Prices, 1747-1775 Year Price per pound of indigo in shillings 1747 2.4 1750 2.75 1755 4.4 1760 3 1765 3.3 1770 3.75 1772 5.5 1775 4.4 Source: Adapted from Figure 6.12 in Marc Egnal, New World Economies: The Growth of the Thirteen Colonies and Early Canada. Indigo was drawn into the nearly nonstop series of wars involving the British, French, Spanish, Austrians and other European powers in the late 1600s and early 1700s. These wars are called by different names in U.S. and World History. Table 3: Wars of the Colonial Era Dates American Name World Name 1688-1697 King William's War War of the League of Augsburg 1701-1714 Queen Anne's War The War of Spanish Succession 1740-1748 King George's War The War of Austrian Succession 1756-1763 The French and Indian Wars The Seven Years' War During the War of Jenkins Ear in 1739, shipping rates increased and rice prices fell, making South Carolina planters receptive to Eliza Lucas' indigo experiment. Having seen the threat to indigo supply posed in the 1740s due to King George's War, the British government took measures to encourage South Carolina's indigo experiment. Beginning in 1748, Parliament authorized a 6-penny per pound bounty (subsidy) on indigo, the better to compete with the French. Britain imported indigo not only for civilian use but to dye British militia and sailor's uniforms blue, both in the British Isles and in North America. South Carolina's indigo exports flourished during the 1750s so that by the outbreak of the French and Indian War, Britain could end imports of French West Indies indigo. During the war, the value of South Carolina's indigo shipments surpassed rice, since indigo was more compact to ship, consequently lowering freight costs and wartime cargo insurance. Indigo entered the American Revolution as the dye for the blue coats, which became the uniform of the Continental Army (in contrast to the "red-coats" of the British regular army.) When U.S. paper currency (continentals) proved worthless, cubes of indigo dye were used in place of money. Although she was the daughter of a British officer, Eliza Lucas Pinckney supported the patriot cause in the American Revolution. A widow by the outbreak of the war (Charles had died in 1758), Eliza saw her plantations destroyed by British raiders. Her greatest contribution, however, was made through her two sons, Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (who fought in the continental army was captured and became a signer of the U.S. Constitution) and Thomas Pinckney (wounded and captured in the Revolution and later governor of South Carolina.) So great was Eliza Pinckney's stature, that when she died of cancer in 1793, George Washington requested to serve as one of her pallbearers. Indigo and Liberty "...one of the British indigo planters had said, perhaps in a moment of anger, "This fellow Gandhi always moves about in crowds, he is always surrounded, but if I find him alone, one day I am going to kill him." Gandhi heard that. Next day, early in the morning-- really early, because Gandhi said his prayers at 4 a.m. and this was before his prayers--he went out ... to the indigo planter's village and knocked on his door. The British planter was furious: Who was knocking at his door in the middle of the night? When he opened it he found Gandhi, who said: 'I have heard that you have taken a vow to kill me if you find me alone, so I have come to make you fulfill your vow.' That was confidence in the adversary." --Narayan Desai, Growing Up With Gandhi, 1987 With the end of the British bounty to North American indigo growers and Britain's switch to Indian indigo, indigo prices collapsed. Additional competition was posed by high-quality French and Guatemalan indigo, which could be harvested up to five times a year (in contrast to a maximum of three harvests in North America.) Natural obstacles arose, as well. Efforts by Mississippi planters to expand the indigo frontier (1790-1794) were thwarted by grasshoppers. The indigo fields of northeastern Florida and coastal Georgia were repeatedly decimated by hurricanes in the early 1800s. With the invention of the cotton gin, which enabled planters to make greater profits in cotton, indigo fields were replaced with cotton. Other planters turned to corn, which was much easier to cultivate. By 1800, commercial indigo production in the southern United States had virtually vanished. Neither the American Revolution nor the collapse of the indigo economy brought freedom to the enslaved Africans and African American of the South, who continued to labor in cotton, sugar, rice, and tobacco fields until the Emancipation Proclamation and the Thirteenth Amendment liberated them. Ironically, slaves would seek out wild indigo (along with pokeberry) to add a bit of color to the plain "negro cloth" their owners might clothe them with. Field Worker James Johnson reported in a Federal Writers' Project Slave Narrative based on an interview with Patience Campbell in 1936, "Although the cloth and thread were dyed various colors, she knows only how blue was obtained by allowing the indigo plant to rot in water and straining the result." Yet, indigo was curiously involved in liberty ... and oppression, for 150 years after its U.S. heyday. When Toussaint Louverture, Henry Christophe, and Jean-Jacques Dessalines led the slave revolution (1791-1804) that successfully expelled the French from St.-Domingue and won Haiti its independence, indigo production plummeted and the world turned again to India to supply it with indigo. During the Seven Years War (French and Indian War), on June 23, 1757, British forces under Robert Clive had decisively defeated the French in India at the Battle of Plassey. For the next century, the British East India Company dominated India. British colonizers accelerated the cultivation of indigo, requiring raiyats (sharecroppers or tenant farmers) to devote 15% of the best portion of their rental land to indigo production (tinkathia), rather than to sustenance crops. These coerced Indian indigo workers supplied British textile mills in the infancy of the Industrial Revolution with blue dye. At the same time, Indian textile production plummeted, suppressed so it would not complete with British textile mills. India became an exporter of raw materials rather than fine textiles. At the time of the Sepoy Mutiny in 1857, indigo planters of the Bihar district of India revolted against British indigo landlords. Although they were defeated and the British Crown incorporated India into the British Empire, the story was turned into an anti-indigo drama, Nil Darpan (The Mirror of Indigo) and translated into English stirring some the consciences of some Britons. In 1865, German scientist Johann Friedrich Wilhelm Adolf von Baeyer began a study of indigo, which lasted until 1880, when he synthesized indigo. His discovery three years later of indigo's chemical structure helped him to earn the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1905. German manufacturer BASF successfully produced synthetic indigo dye derived from coal tar in 1897, and within 10 years natural indigo imports plummeted by 90 percent. As demand shifted to the synthetic dye, natural indigo prices collapsed. In an attempt to make up for lost earnings, British planters required their Indian indigo tenants to make payments to them to receive a waiver on indigo production while, at the same time, still requiring them to pay their indigo obligation (tinkathia). Strapped for cash, desperate indigo workers often had to agree to 12 percent usury loans which further enriched their British landlords. Desperate Indian indigo workers found their greatest champion in 1917. Sharecroppers working the indigo plantations in Champaran (Bihar, India) appealed to Mahatma Gandhi. Disobeying the order to leave the moment he arrived, Gandhi was arrested and jailed. When a huge crowd of protesters appeared outside the court shouting slogans, Gandhi warned them that: "Any violent act will hurt our cause." Some scholars contend that this was the first time that Gandhi declared in India his principle of satyagraha (non-violent resistance). Although the crowd dispersed peacefully, the intimidated British officials dropped the case against Gandhi and allowed him to stay and investigate the indigo workers' claims. He interviewed nearly 8,000 peasants and published a scathing report about their exploitation. Consequently, the government passed a relief bill for the workers known as the Champaran Agrarian Bill. Gandhi earned national and international stature standing up for the oppressed indigo workers, which gained momentum until he had succeeded in winning India's independence, in 1947. Indigo had come full circle, in its homeland, becoming a symbol of liberty rather than oppression.