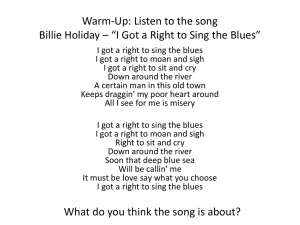

The blues music tradition and the styles that it has engendered

advertisement

Eric Clapton, Eric Burdon, and British Renderings of American Blues in the 1960s Steve Armour Final Capstone Project Dr. Oetter 26 April 2010 Armour 2 The blues music tradition and its derivative styles currently enjoys popularity all over the world. Rock radio listeners cannot tune into a station for very long without hearing an instrumental phrase or a certain type of vocal inflection that had some origins in early blues. Over the past fifty or sixty years, the face of blues music has evolved so that British figures such as Keith Richards, Jimmy Page, and Eric Clapton have come to tower over their audience as “quintessential” purveyors of the form just as much or more than early luminaries like Robert Johnson and Son House. Some of the reasons for this are obvious. White performers thrived with the white audience, which was large, avid, and often deeppocketed. But an interesting phenomenon is occurring before this commercial aspect even enters the equation. What actually caused these British musicians to take up the blues in the first place? When a meaningful cultural expression created by a socially downtrodden people in remote areas moves beyond its cultural enclave to enter the popular imagination, some significant cross-cultural activity is occurring. The issue has value in terms of identity, perceived authenticity, and intellectual property for both the original performers and those who would later borrow from it and build upon it. My goal for this research project is to explore the relationship between racial and ethnic identity and the blues as a cultural expression through an examination of key British blues performers Eric Clapton and Eric Burdon. My project will include an investigation of how these performers and the white audience have interpreted (and sometimes manipulated) the musical form to construct a unique interaction and identification with a culture that has been historically marginalized. I will tackle these issues by exploring the existing literature about the blues as both a musical form and cultural language, including biographical accounts of select performers, musical histories, lyrical texts, journal articles, and songs. Armour 3 The Blues as an African-American Expression At least a cursory understanding of the blues music culture in the United States is critical to a discussion of the later British blues boom and its relation to the original music. Historians vary on how far back they choose to go when citing a point of origin for the blues. A detailed account of blues history will take us back to West Africa, where many of the important features found in blues have their beginnings. In particular the countries of Senegal and Gambia revealed a music culture that would be transferred in small ways to the American South due to the American and European slave trade. Notably, this region of the continent is very dry and lacking in forests, which means that wooden drums were scarcer here than in other parts of sub-Saharan Africa. Gourd-based lutes and harps, however, which usually had one to four strings, were a common instrument in this area1. The presence of these stringed instruments in West Africa probably influenced some of the crude guitar-like instruments that blacks made from found objects once they were transplanted to the American south and may explain their willingness to pick up the guitar once it became available. Other features of West African music that show up later in the blues include a driving rhythm, call-and-response vocals (and audience participation in general), and the use of blue notes or bent notes. This “imprecision” of pitch has long been a staple of African and African-American music music. As Robert Palmer describes, “European and American visitors to Africa have often been puzzled by what they perceived as an African fondness for muddying perfectly clean sounds.”2 West African vocal treatments can be characteristically guttural and instruments are commonly altered with tin sheets to achieve 1 2 Palmer. Deep Blues, 27. Ibid., 30. Armour 4 a rough, noisy, buzzing or rattling sound. These characteristics have continued to appear in black music and are an important part of blues. A very important step in the evolution of blues is the conglomeration of field hollers, work songs, and spirituals that African-American field workers sang on plantations, a socially important type of music that works as somewhat of an intermediary between West African sounds and the blues. In particular, blue notes and call-and-response vocals were present in these expressions, both of which can be found in the music that preceded and followed work songs.3 After the Civil War, as instruments became available to freed blacks, the tradition of these work songs continued and the vocal parts fell into more formalized patterns, namely the twelve bar blues (three lines, each four bars long).4 But what is most important to this discussion, perhaps, is the social meaning of the blues in America. Many examples of the blues chronicle the struggle against poverty, oppression, and self-loathing that plagued African-Americans during the Jim Crow era and the period that followed. Essentially, the blues arose from African musical forms and themes that were adapted to the settings of slavery, sharecropping and the trials of virtual non-citizenship. Thus, the blues is situated as a uniquely African-American artistic expression. This observation has led to a great debate among scholars about who can “legitimately participate” in the making and continuation of the blues in terms of race and ethnicity. Joel Rudinow and Paul Christopher Taylor have debated in corresponding journal articles about the nature of race, identity and the blues. These articles pick apart many issues about race, ethnicity, identity, and authenticity involving the blues: Do African- 3 4 Ibid., 33. Baraka. Blues People, 68. Armour 5 Americans have an exclusive cultural claim to the blues? Can white people sing the blues? Should we consider the blues a “racial project”?5 These issues are very complicated and every argument seems to have at least some partial truth, but is always marred by the abstract nature of the subject matter. But certainly as the blues has disseminated into the popular imagination, one can make some justified claims about how it has been interpreted and used by those outside of the music culture in which it developed. Some, such as Amiri Baraka with his theory of “The Great Music Robbery” maintain that black music has historically been “stolen” by the white music establishment and redelivered to the white audience in a form that they will deem more acceptable, without giving credit to the original (black) creators.6 Although Baraka’s concerns about the commercially-driven white appropriation of black music may be well warranted, we should be careful not to invest too strongly in his idea of cultural theft. Cultural exchange and fusion exists in nearly every culture in the world and this is generally not viewed as a moral conundrum because cultures do not exist in a vacuum. Instead, cultural borrowing can be a way for people to make sense of their own circumstances through the lens of another culture, even if in doing so they are making false assumptions about that culture, which is really what my investigation of British blues is about. The Blues Comes to Britain Rudinow. Race, Ethnicity, and Expressive Authenticity, 127, 130; Taylor. So Black, So Blue…Response to Rudinow, 314. 6 Baraka. The Music, 328-332. 5 Armour 6 The British blues movement (sometimes called the “boom” or “revival”) is a significant example of cross-cultural transmission and reception because it is the pinnacle of white or non-American engagement with the blues, spawning a fanaticism that continues today, particularly among white Westerners. British blues would have its day as a profitable genre, but, for reasons we will see later, the role of commercial interest in its development should not be overstated. Since virtually the beginning of the recording age, black music has always been well-received in Britain. Before and throughout the blues movement, jazz was of wildly popular interest. Many of those who took interest in the blues were art school students, a type of citizen “trained to accept new ideas yet suspicious of authority and its promises of a transformed society.”7 This suspicion arose from the political rhetoric of the 1950s that claimed England was moving towards a utopian state of affluence and classlessness. Young people took this to mean that they would be forced into the drudgery of unskilled work for the rest of their lives and they resented the disparity between the promises of their leaders and the unsatisfying reality of postwar England. Their frustration led them to empathize with marginalized populations, and they “appropriated the blues as a signifier to define and reflect their sense of otherness.”8 In the 50s and 60s, British ideas about the blues were very much steeped in mythology. As rock guitarist Pete Townshend says of this time, “America was still a distant and evocative IDEA to us, full of mystique.”9 Townshend is suggesting that young Britons were fascinated with America to the point of romanticizing, viewing it as a metaphor for excitement and freedom. It was also seen as attractively dangerous and transgressive since 7 Schwartz. How Britain Got the Blues: The Transmission and Reception of American Blues Style in the United Kingdom, 74. 8 Ibid. 9 Townshend. Liner notes. The Who. Who’s Missing. LP. Polydor, 1988. Armour 7 conservative British nationalists saw America as a “corrupting influence on native cultural institutions,” 10allowing the younger generation to reject social conformity through contact with another culture. Eric Clapton explains his fascination with America: The first books I ever bought were about America. The first records were American. I was just devoted to the American way of life without ever having been there. I wanted to learn about red Indians and the blues and everything. I was really an American [sic] fan.11 Ulrich Adelt reads into the subtext of Clapton’s words and makes the rather astute observation that Clapton’s elation with all things American is “closely linked with an imagined otherness” hence the mention of blues and “red Indians.” For British blues fans at this time, America was often seen through the lens of its conflicts and contradictions, particularly those with racial implications. It is probably no accident that the blues became a transatlantic obsession at the height of the American Civil Rights Movement. As it played out, the blues became the story of the underdog, the downtrodden, and the destitute, which the British identified with however disparate the two situations actually were. The social unrest was serious enough, yet distant enough, to appear exciting to them. Eric Burdon maintained that the constant fighting between his fellow travelers Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis on their 1963 tour of England made their bus “a four-wheeled microcosm of America’s biggest social problem.” After describing the chaos of their altercations, he concludes, “We couldn’t wait for the excitement of America.”12 One factor that made the importation of American blues into Britain such a remarkable situation is that the British audience itself was made up of radical purists. This tendency applies well to Britain’s preceding jazz scene, in which a conflict between 10 Schwartz. How Britain Got the Blues: The Transmission and Reception of American Blues Style in the United Kingdom. 11 Graham and Greenfield. Bill Graham Presents: My Life Inside Rock and Out, 216. 12 Burdon and Marshall. Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood, 19. Armour 8 aficionados of “trad jazz” (from 1920s New Orleans) and “modern jazz” (be bop of the 1940s) revealed the harsh scrutiny of the trendy young British when deeming a musical sound “pure.” As the nascent blues scene continued to grow in Britain, blues fans latched onto often dated ideas about what constituted the blues. At the 1958 Leeds Folk Festival, for instance, Muddy Waters and Otis Spann were booed by the audience for playing electric instruments.13 This is a remarkable thing to consider since Muddy Waters had been playing the blues in the Mississippi Delta since about 1932, several years before the electric guitar was even being played widespread and likely before anyone in the audience had even heard of the blues. In other words, it would be odd to question Waters’ authenticity in this situation. It seems as though he was only continuing the development of a medium he helped cultivate in the first place. After all, the blues is a living cultural expression, not something locked in time as a remnant of a mythical past. If anyone at this time could have played the electric blues with honesty and integrity, would not it have been Muddy Waters? But in the opinion of a stubborn British youth, Waters’ performance did not live up to their ideas about the blues. For them, somewhat arbitrarily, “true” blues could only pour from the hollow body of an acoustic guitar. Of course, a mere four years later Waters would return and try to appease the crowd with an acoustic set, only to once again disappoint an audience who by this time was immersed in a British blues scene dominated by electric guitars.14 Sometimes blues enthusiasts associated authenticity with their perceptions of blackness, giving way to stereotypes about black life in the South in the process. One critic praised a performance by blues players Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee for creating a 13 14 Adelt. “Trying to Find an Identity: Eric Clapton’s Changing Conception of ‘Blackness,’” 435. Ibid. Armour 9 “genuine” blues atmosphere at their London concert, characterized by “swirling mist” from the bayou, “Spanish moss,” the sound of hounds, and “the low, far-off cry of the freight train”15. Valerie Wilmer comments similarly on a Jesse Fuller performance, writing “As he swings along you can hear the roar and whistle of the freight train; you can smell the scent of dried grass and the cotton field; you can see the black bodies sweating as they line the tracks—you know you are listening to the real thing.”16 Blind Willie Johnson was reviewed as “a chiller, a dark-night, fire-and-brimstone Christian singer of voodoo propensities. In a dim room you listen to a down bound train carving a relentless way through a black mistdrenched Louisiana night…”17 It seems curious the degree to which mist and freight trains became emblems of the rural South for the British music press, but what is more unsettling is how the image of blacks laboring on a chain gang is conjured up to indicate authenticity. In effect, black social pain and hardship becomes the basis by which British listeners can validate their taste. Also troubling is Tony Standish’s association of Blind Willie Johnson (a native of Texas, not Louisiana) with voodoo, a common stereotype conflating Southern black religious practices and “black magic.” What writers and fans were essentially doing was giving in to romantic ideals about the blues. The issue of romanticism is important to understanding the relationship between British blues and earlier American blues. Later, we will see this especially in Eric Clapton’s romantic notions about the blues. As George Lipsitz explains, “The enduring appeal of romanticism in art and music in Western culture testifies powerfully to the very real alienation and isolation of bourgeois life, as well as the oppressive and relentless 15 Schwartz. How Britain Got the Blues, 99. Ibid, 100. 17 Ibid. 16 Armour 10 materialism of capitalist societies.”18 For British blues enthusiasts, the blues was an escape into something thought to be real, pure, and frozen in time. They felt that it freed them from the triviality and emptiness of commercial culture, which is ironic since they were actually discovering the blues through commercial outlets (In fact, while many British blues fans made a point of tracking down the most obscure music available, their initial attraction to blues was often sparked by widely marketed rock ‘n’ roll artists like Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry, and Fats Domino). But their romanticism of the blues in this way is harmful because it “maintains the illusion that individual whites can appropriate aspects of African American experience for their own benefit without having to acknowledge their structural relationships with actual African Americans.”19 Eric Clapton’s Identity and Conceptions of Race Eric Clapton is a fine reference point for how British blues followers engaged in an appropriation of the blues to self-identify, and how it guided their ideas about race. The aforementioned sense of “otherness” that he saw in blues performers and his identification with the blues was crucial to Eric Clapton’s development. In his own words, he felt my back was against the wall and that the only way to survive was with dignity, pride, and courage. I heard that in certain forms of music and I heard it most of all in the blues….It was one man with a guitar versus the world…when it came down to it, it was one guy who was completely alone and had no options, no alternatives other than just to sing and play to ease his pains. And that echoed what I felt.20 Clapton’s perceived lack of “options” and “alternatives,” must be viewed in a relative context, and this goes for all British blues enthusiasts who saw something of themselves in the hardships of African-Americans. The opportunities that were open to Clapton as a working-class Briton far outmatched those of black Americans before the Civil Rights Lipsitz. “Remembering Robert Johnson: Romance and Reality,” 43. Ibid., 40. 20 Sandford. Clapton: Edge of Darkness, 22. 18 19 Armour 11 Movement. But as we learn more about Clapton we find that his skewed comparison is part of his search for an identity: Now I didn’t feel I had any identity, and the first time I heard blues music, it was like a crying of the soul to me. I immediately identified with it. It was the first time I’d heard anything akin to how I was feeling, which was an inner poverty. It stirred me quite blindly. I wasn’t sure just why I wanted to play it, but I felt completely in tune.21 Clapton’s feelings of being a lonely, dejected youth are important and contribute greatly to his sense of self. What he overlooks, however, is that the “inner poverty” that he sees as a shared bond between him and bluesmen was, for the bluesman, often informed by a very real material poverty.22 But it seems that Clapton and British blues fans rarely bothered with acknowledging the realities of black experience. In their minds, feeling sad and disheartened with your own society was enough to afford you a genuine empathy with an oppressed people. As it turns out, Clapton’s sense of identity is frequently tied to race. Consider that upon meeting Jimi Hendrix Clapton determined him to be “the real thing” before even hearing him play, claiming “If I was black, I would be this guy.”23 Clapton’s comments indicate his struggle with his own whiteness and sense of authenticity and show him investing in racial essentialism concerning the blues. One of Clapton’s earliest encounter with the blues was seeing Big Bill Broonzy on television playing in a nightclub under the eerie, swaying glow of a single light bulb. He remembers hearing the blues as something he recognized immediately. “It was as if I were being introduced to something that I already knew, maybe from another, earlier life,”24 he states in his autobiography. His most telling description of blues and its effect on him calls 21 Coleman. Clapton! The Authorized Biography. 28. Adelt. “Trying to Find an Identity,” 437. 23 Platt. Disraeli Gears: Cream, 26. 24 Clapton. Clapton: The Autobiography, 33. 22 Armour 12 it “primitively soothing,”25 a troubling characterization of the blues that recalls stereotypes of an “uncivilized” African culture. Clapton’s first memories of his obsession are vague, perhaps even to him, but are quite telling in terms of his identity and ideas about the blues. By understanding the blues as something that he could have experienced in a past life, Clapton connects this culturally constructed phenomenon—one developed an ocean away—to his own being. Spiritually connecting himself to the blues is something that Clapton would virtually make into a career, and nowhere is this more apparent than in his open obsession with Robert Johnson. Throughout his career Clapton was more vocal about his appreciation for Robert Johnson than any other blues artist. He became enamored with Johnson’s music for the first time after a friend lent him the record King of the Delta Blues Singers, a collection of Johnson’s 1930s recordings. In the liner notes he discovered that Johnson auditioned for these sessions in a San Antonio hotel room where he played facing the corner because he was so shy. Clapton was captivated by this tidbit of trivia because he had himself been paralyzed by shyness as a child. He also identified with the song “Hellhound on My Trail,” which, he says, seemed to channel things he had always felt:26 I got to keep moving, I got to keep moving Blues falling down like hail, blues falling down like hail Mmm, blues falling down like hail, blues falling down like hail And the day keeps on remindin' me, there's a hellhound on my trail Hellhound on my trail, hellhound on my trail27 “Hellhound on My Trail” describes a man in a ceaselessly distressed condition who must “keep moving” to avoid succumbing to his troubles. Clapton had his share of problems and challenges. He was born illegitimate and raised by his grandparents, he had many troubles 25 Ibid. Clapton. Clapton, 40. 27 Johnson. “Hellhound on My Trail.” 26 Armour 13 with woman and drugs, and he lost his four-year-old son in 1991. Although Clapton purports a shared emotional bond with Johnson, “on his best day, Robert Johnson caught more hell than Eric Clapton had ever imagined.”28 Johnson grew up in the segregated South, a world of hard labor, unfair wages, and lynch mobs. By associating himself with Johnson, Clapton affords himself a sense of authenticity and emotional depth. What Clapton fails to acknowledge are the social and economic conditions that allow him rather than an AfricanAmerican to gain tremendous wealth by playing African-American music.29 Moreover, Clapton romanticizes the plight of long dead blues players, but shows little sympathy for the oppressed minorities in the here and now. His vocal support of segregationist politician Enoch Powell at a concert in Birmingham, England in 1976 drew waves of controversy, as well his antagonistic comments aimed at immigrants.30 Robert Johnson is the subject of great mythologizing by blues listeners and the commercial world. Central to this is the famed crossroads story, in which Johnson acquires amazing talent by trading his soul to the devil at the intersection of two roads. The story has spread to become the pinnacle of blues myth. It is the subject for his 1937 song “Cross Road Blues,” later covered by Clapton as “Crossroads.” It is also the basis for the 1986 film Crossroads and has been used extensively in Mississippi to promote tourism. Although the story has great appeal as a captivating piece of folklore, it has very real implications. In West African culture, the crossroads image serves as a metaphor for decision-making and potential, just as it does in Western culture. The “devil” in this scenario is actually the deity Eshu-Elegbara, not an evil being, but an unpredictable figure Lipsitz. “Robert Johnson,” 42. Ibid., 43. 30 Adelt. “Trying to Find an Identity,” 447. 28 29 Armour 14 with the power to make things happen.31 Lipsitz suggests that when Johnson’s relatives and fans—who first reported the crossroads story to a historian—were interpreting Johnson’s story, they were understanding it through the lens of African folkways and beliefs that allowed them to make sense of their plight as second-class citizens in America. Another way of understanding the crossroads story is through a historical lens. There is evidence in the lyrics of “Cross Road Blues” that Johnson is speaking about a social code that affected many African-Americans in the early 20th century: the dangers of being a black person caught alone in an unfamiliar place after dark. I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees. I went to the crossroad, fell down on my knees. Asked the Lord above,“Have mercy save poor Bob, if you please. Mmmmm, standin’ at the crossroad I tried to flag a ride. Didn’t nobody seems to know me, everybody pass me by. Mmm, the sun goin’ down, boy, dark gon’ catch me here. Oooo ooee eeee, boy, dark gon’ catch me here. I haven’t got no lovin’ sweet woman that love and feel my care. You can run, you can run, tell my friend poor Willie Brown. You can run, tell my friend, poor Willie Brown Lord, that I’m standing at the crossroad, babe, I believe I’m sinkin’ down.32 The sense of distress in this song is clear as Johnson desperately tries to flag down a ride from a friend or kind stranger before being spotted out after the sun goes down. Johnson was reacting to a well-understood and harshly enforced behavioral code of the Jim Crow era that attempted to push African-Americans to the fringes of society. The song comments on “only one aspect of an elaborate apparatus that circumscribed the actions of black Southerners [but] underscore[s] the precariousness and vulnerability of black life”33 at this time. Lipsitz. “Robert Johnson,” 41. Johnson. “Cross Road Blues.” 33 Litwack. Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow, 410-411. 31 32 Armour 15 Clapton’s romanticizing of Johnson, his proclaimed identification with his pain, and the mythology that is used to sell music, movies, and tourist attractions do little to afford us any real understanding of the social circumstances that informed his music and the blues as an expression. This can only be done by looking past the myth and the magic that is supposed to make the blues “pure” and “real,” and by analyzing the world that these people actually lived in. Adopting the Code Since the blues became a way for British youths to understand and comment on their own society, it was natural for them to adopt one of the most important aspects of any artistic idiom: the language. No artist did this quite so often and with such self-awareness as the Rolling Stones. Mick Jagger, not surprisingly, declared early on obsession with blues and R&B, considering it “the most real thing I’d ever known.” 34 This “realness,” or notion of authenticity stood in direct contrast with the “puritan ethic” of white middle-class Britain, namely “sexual repression, status seeking, and goal-oriented labor” (368).35 They stood out from the pack as particularly imitative of black styles, most notably Jagger’s singing voice which he sometimes bent and shaped to achieve an almost parodic “black” sound. In it’s original incarnation, the blues argot was a way for black musicians and black audiences to both reject the vocabulary of the dominant culture and to skirt the strict standards of censorship that would never permit their sexual wordplay (and sometimes criticisms of whites) if not cleverly guised by these code words. Words such as “jelly roll,” “ya-yas,” and “rooster” replaced terms for sexual body parts and acts. John M. Hellman, Jr. explains the sexual nature of blues lyrics: “First, sex is generally the obsessive interest of Oberbeck. “Mick Jagger and the Future of Rock,” 45 Hellman. “’I’m a Monkey”: The Influence of the Black American Blues Argot on the Rolling Stones,” 368. 34 35 Armour 16 groups that are denied any other means of entertainment and achievement; second, sex is a natural and strong metaphor for power relationships, of which the oppressed black man was acutely aware.”36 In their early years the Rolling Stones frequently performed renditions of songs by black blues artists. Songs like Slim Harpo’s “King Bee” and Howlin’ Wolf’s “Little Red Rooster,” contained veiled phallic imagery, animalistic sexual content, and sexual boasting. The Stones would eventually adopt many of these devices in their own songs, from the boastful “Let’s Spend the Night Together,” to the eroticism of “Parachute Woman,” and Mick Jagger would go on to become something of an international sex symbol.37 When considering the reasons for their use of sexual content, it is important to remember that the Stones were not “denied any other means of entertainment and achievement.” They were middle class Londoners who could have gone on to any number of successes. Sex was also not their only outlet for a dominant or powerful role. In other words, they were not members of a systemically oppressed community. Furthermore, the Rolling Stones would invoke the sexual nature of the blues to heighten their own sex appeal, which is somewhat ironic since the black male sexuality they were channeling has been historically viewed by polite society as a threat to white “innocence.” If black blues singers were to discuss matters of sexuality in their songs at all, the stereotype of the black man as a sexual threat is one factor that made the original blues argot so important. Eric Burdon’s Music, Guilt, and Relationship with Blues “Authenticity” It is remarkable how much artists within the British blues revival strived for authenticity. If there is any such thing as authenticity in this context—and the matter is 36 37 Ibid., 369. Ibid., 370. Armour 17 certainly open to debate—could it really be earned? Members of the 60s pop blues group The Animals seemed to think so. Hailing from the industrial town of Newcastle in Northern England, lead singer Eric Burdon had an untamed fascination with the American South, black music, and the credibility he felt he could buy himself by channeling these associations. Sometimes he did this to the point of dishonesty, falsely attempting to attribute their 1964 rendition of “House of the Rising Son” to an early version by a black musician, hoping that that this would heighten the Animals’ status as supremely authentic. The rest of the band and most of the public understood that the Animals’ version stemmed quite directly Bob Dylan’s version, released just two years earlier.38 Connecting their music to “blackness” was important to Burdon. As we have seen before, “blackness,” in this scenario, equals genuineness, and the Animals were quite skilled at mimicking black sounds. As band biographer Sean Egan would say, “The Animals sound[ed] more uncompromisingly black than any of the countless bands who saw chart action in the wake of the Beatles, including the Rolling Stones.”39 Later in his career this fact would result in identity problems for Burdon. Eric Clapton sometimes downplayed his talent on the basis of his race, but Burdon took this a step further, expressing guilt that he was able to gain success by playing the music of a community prevented from such opportunities. “Black music gets you there,” he said, “and when you get there, you can’t go no place, if you’re black. But if you’re white and you play black, you can go anywhere you want.”40 Burdon’s recognition of his own privilege is interesting. According to Brian Ward, Burdon’s dilemma revolved not around “whether whites can really play the blues, but Ward. “That White Man, Burdon: The Animal, British Beat Music and the American South,” 3-5. Egan. Animal Tracks, 60. 40 Burdon. Animal, 94. 38 39 Armour 18 […]whether whites should even try to express themselves using the music of a community of which they are not members, grounded in historical experiences they never share.41 Somewhat contrary to Burdon’s rejection of his “playing black,” was his decision to front the all black funk band War at the end of the 1960s. Burdon describes the bands early rehearsals as a bit awkward because he was so accustomed to playing blues-based rock, realizing, “They didn’t listen to the blues and didn’t want to play it. American blues meant one thing to a group of black guys from Long Beach and quite another to people like me, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and Keith Richards.”42 Perhaps the idea Burdon is touching on to here is same one that Ward references and the one that this thesis has been investigating all along: the idea that blues is embedded in a historical and social context of which race is a crucial element. Why would a black band from Long Beach not want to play the blues? Perhaps for them it represents the state of desperation and misery that has afflicted their community for too long, and they would prefer to speak out against institutionalized injustice rather than cast themselves as victims. Or maybe they just don’t like the blues. But there is no denying that, particularly after Burdon’s departure from the group, War became part of a coterie of funk and soul artists that would emphasize black pride, racial tolerance, and social justice in their lyrics and imagery, peaking with their gritty depiction of black urban life, “The World is a Ghetto.” They consistently infused these messages into their music with an upbeat, celebratory sound that seemed almost consciously antithetical to blues. This phenomenon suggests that by the end of the 1960s, when many white blues rock bands were just getting started, there 41 42 Ibid., 14. Burdon and Marhsall. Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood, 107. Armour 19 was a movement in the African-American community away from the tragic and pitiable subject matter of the blues toward much more lively and empowering fare. In some ways, Burdon is a foil for Clapton. Clapton insists, “I had never really understood, or been directly affected by, racial conflict,” owing this condition to music, which has “helped me to transcend the physical side of that issue.”43 As we have seen, however, Clapton’s musical journey has in fact involved his perceptions of race (recall his premature comments on Jimi Hendrix among other things). Burdon, on the other hand, faced issues of race head-on and recognized the contradictions in his performance, stating very plainly in 1967, “I was trying to express myself in the past, but I was also trying to escape. I wasn’t being myself. It wasn’t me that was singing. It was somebody trying to be an American Negro.”44 Once Burdon observed racial bigotry first-hand in the American South—watching a black GI be turned away from a New Orleans music venue and witnessing a Klan parade—he became disillusioned with his own image.45 In Conclusion When British blues revivalists were first adopting the blues and appropriating it for their own purposes they were staunchly anti-commercial. In fact, the blues’ apparent lack of commercial viability is one of the things that made it so appealing to them as they shunned popular culture and England’s postwar efforts to stimulate mass consumerism.46 Ironically, the British blues explosion eventually helped usher blues-based music onto the global stage and into the realm of cultural commodities. 43 Clapton. Clapton: The Autobiography, 94. Melody Maker, August 15, 1967, p. 5 45 Ward. “That White Man, Burdon: The Animals, British Beat Music and the America South,” 12. 46 Schwartz. How Britain Got the Blues, 75. 44 Armour 20 Over the past 40 years or so, the image and idea of the blues has been applied in popular films, television, and visual art, and has been used to sell everything from automobiles to cigarettes. Much of the mainstream attraction that makes it such a workable marketing tool stems from the same disconnected ideas about the blues that British performers held in the early 60s: its sense of cool, rebellion, realness, and sex appeal. Unfortunately, this detachment has problematic consequences. As Daniel Lieberfeld says, “Because of blues culture’s commercialization and accompanying loss of social context, the white imagination ignores or romanticizes the poverty, violence, and endurance that bred and fed the blues.”47 47 Lieberfeld. “Million Dollar Juke Joint: Commodifying Blues Culture,” 3. Armour 21 Bibliography Adelt, Ulrich. "Trying to Find an Identity: Eric Clapton's Changing Conception of “Blackness”." 433-452. Routledge, 2008. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 26 Oct. 2009. Baraka, Amiri. Blues People: Negro Music in White America. New York: William Morrow, 1963. Baraka, Amiri. The Music: Reflections on Jazz and Blues. New York: William Morrow, 1987. Burdon, Eric, and Craig J. Marshall. Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2001. Clapton, Eric. Clapton: The Autobiography. New York: Broadway Books, 2007. Coleman, Ray. Clapton! The Authorized Biography. New York: Warner Book, 1986. Egan, Sean. Animal Tracks: The Story of the Animals: Newcastle’s Rising Sons. London: Helter Skelter, 2001. Hellman, Jr., John M. “’I’m a Monkey:’ The Influence of The Black American Blues Argot on the Rolling Stones. The Journal of American Folklore. 86.342. 1973: 367-73. http//www.jstor.org/stable/539360. 24 Jan. 2010. Katz, Bernard, ed. The Social Implications of Early Negro Music in the United States. New York: Arno, 1969. Lieberfeld, Daniel. "Million-dollar juke joint: Commodifying Blues Culture." African American Review 29.2 (1995): 217. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 26 Oct. 2009. Armour 22 Lipsitz, George. Remembering Robert Johnson: Romance and reality. " Popular Music and Society 21.4 (1997): 39-50. Research Library, ProQuest. Web. 26 Oct. 2009. Litwack, Leon F. Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1998. Oberbeck, S. K. “Mick Jagger and the Future of Rock.” Newsweek. Vol. 77, No. 1. January 4, 1971. Palmer, Robert. Deep Blues. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Penguin, 1982. Platt, John A. Disraeli Gears: Cream. New York: Schirmer Books, 1998. Rudinow, Joel. "Race, ethnicity, expressive authenticity: Can white people sing the blues?" Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism 52.1 (1994): 127. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 26 Oct. 2009. Sandford. Christopher. Clapton: Edge of Darkness. New York: Da Capo Press, 1999. Schwartz, Roberta Freund. How Britain Got the Blues: The Transmission and Reception of American Blues Style in the United Kingdom. Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2007 Taylor, Paul Christopher. "...so black and blue: Response to Rudinow." Journal of Aesthetics & Art Criticism 53.3 (1995): 313. Academic Search Complete. EBSCO. Web. 26 Oct. 2009. Ward, Brian. Unpublished paper. “That White Man, Burdon: The Animals, British Beat Music and the American South. Southern Historical Association Conference. University of Manchester, 2009. Copy in possession of the author.