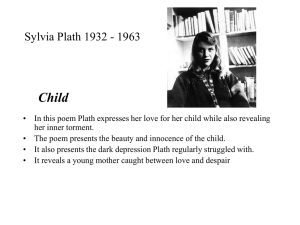

Print friendly Ted Hughes and the corpus of Sylvia Plath Sarah

advertisement