2011 HSC Paper 2 Section III Module C Explore how the poetry of

advertisement

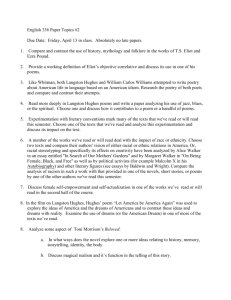

2011 HSC Paper 2 Section III Module C Explore how the poetry of Ted Hughes and ONE other related text of your own choosing represent conflicting perspectives in unique and evocative ways Prescribed text: Birthday Letters by Ted Hughes, 1998 (Poetry) Related text: Autumn Laing by Alex Miller, 2010 (Novel) Opening general sentence about controversy which links the two texts with the idea of conflicting perspectives and then is narrowed to the topics of creativity and relationships Writers and artists attract controversy. In breaking barriers they develop new creative forms that challenge accepted perceptions and lead to conflicting perspectives about their work. But often the divided opinions are not just about the act of creativity but about the relationships of people around them. Divided opinion around fraught relationships is what, paradoxically, connects British poet, Ted Hughes, with Australian artist, Sidney Nolan. Ted Hughes’ collected poems in Birthday Letters are addressed to his wife, Sylvia Plath, and underpinning them there is a sense of constant conflict as he implicitly attacks her perspective. In his novel, Autumn Laing, Alex Miller creates a new story that uses the relationship of Sidney Nolan (Pat Donlon) with Sunday Reed (Autumn Laing), to explore conflicting views of art and relationships. These two texts use different forms but they both represent conflicting perspectives in unique and evocative ways through careful choices of language. A logical connection is made between the background context of the poems, which is followed by an overview about perspectives in the poems, and then a link to the thesis about relationships The poems in Birthday Letters are memories of events that took place during the turbulent relationship of Ted Hughes with poet Sylvia Plath and as such cannot be divorced from their context. On the surface they are a search for truth, asking questions, thoughtfully considering and weighing up events to come to an understanding. But, underlying this rationality, lies a clear personal agenda, to reclaim Hughes’ reputation from the criticism he faced after his relationship from Plath ended with her suicide. However, even without this knowledge, the poems are defensively responding to perspectives. The thing that links all the poems – apart from the sorting through memories – is the passion of the relationship moving from romantic to violent moments, from critical to wondrous. Uncertainty is explored through the technique of questions A repeated feature of all the poems is uncertainty which is conveyed through such techniques as the use of questions. ‘Fulbright scholars’ opens with a question on place (“Where was it, in the Strand?”) and moves on to questions on people (“Were you among them?”) and then ends with question on actions (“Was it then I bought a peach?”). These questions serve to guide the reader through the process of recovering memory. Hughes examines the photo closely but “not too minutely”. He anticipates attacks on his version of the story when he asserts “I remember that thought” but at the same time he admits that he does not remember her (“Not your face”). Techniques are used to drive the discussion on the poems, showing how language choices influence perspective1 The idea of uncertainty continues, focusing on Uncertainty takes over in the repeated use of the modal “maybe”, 1 These paragraphs may focus on a technique but the techniques are used to support and argument about uncertainty. Just explaining techniques without is not a good way to discuss poems as it can lead to explanation of isolated lines without analysis or synthesis of ideas 1 a different technique – in this case, it is looking at modals and pronouns Long quotations should be indented and do not need to have quotations marks contrasted with the detail of the reference to her appearance “long hair, loose waves – / Your Veronica Lake bang.” This suggestion of attraction and moment of loving is quickly dispelled by the negative phrase, “Not what it hid”, which immediately alerts the reader to a darker side. The elusiveness of the memory is captured in his contradictory admission: “Then I forgot. Yet I remember/The picture: the Fulbright scholars.” The first person pronoun is set against the second person throughout the poem reflecting the subsequent opposition of Hughes and Plath. In the last few lines the poem moves away from the issue of unreliable and oppositional memories stimulated by the photo to the certainty of what he was doing at the time, walking “sore-footed, under hot sun, hot pavements”, when he bought a peach from Charing Cross Station. It is in this section that the poem changes in tone from conflictual to sentimental and even romantic. The purchase of the peach can be seen as a metaphor for the beginning of their relationship which came at a time when he was not comfortable with himself: …the first peach I ever tasted. I could hardly believe how delicious. At twenty-five I was dumbfounded afresh by my ignorance of the simplest things. These last few lines demonstrate the power of the poem and of poetry to convey a point of view. The pleasure of this memory of something new and fresh becomes associated with Plath, despite the uncertainty of how they first met. All the contradictions that characterise the first part of the poem are lost in the certainty of the experience. It is a subtle but pointed comment that illustrates different perspectives in the poem: from factual account of a newspaper photo to a sensual account of the experience of eating a peach, imbued with sexual connotations. The word same connects to last idea The opening is linked to perspectives Supporting evidence is given to continue the argument of the previous paragraph. The paragraph ends with as strong analysis of the purpose of perspectives that related directly to the module and the questions The same passion is a feature of the encounter of Autumn Laing with Pat Donlon in the novel Autumn Laing. The novel opens, like Hughes’ poem, looking back. “They are all dead, and I am old and skeletongaunt.” Autumn Laing remembers the place “in the shadows of the old coach house… Blue smoke in the sunblades cutting the interior dark into shapes – in imitation of a painter we once admired.” This visually intense opening reinforces that this is a novel about a painter and about painting; it also reminds us that perspectives on painters change as time moves on. Autumn Laing’s strong views on artists are not always in agreement with the views of others and she acknowledges this and her own changing perspective as she revisits the past and her memories. She finds a painting by Edith, Pat’s first wife. Autumn’s husband, Arthur Laing, had admired it with musical metaphors as being “…lovely. A piece of music. A little nocturne” but it is only after the passage of time that Autumn realises its merit. “I had never really looked at her painting before … I was so one-eyed in my belief in the rightness … of modernism’s cause that any artist who worked in the conservative tradition as Edith did was automatically excluded from my serious attention.” Autumn’s revelation reveals that perspective is about reinforcing your own beliefs and values, defensively and selectively. Perspectives are not just a personal response: they are philosophical ways of being that are self-preserving, excluding all other views. They are also contextualised, part of different epochs 2 and stages in one’s life. The word epoch in the past paragraph moves on to link with stages… in life The discussion focuses on the effect of the pronoun to convey different perspectives This paragraph continues the ideas developed in the previous paragraph but focusing this time on the metaphors to explore perspectives Sums up the ideas conveyed by the evidence in the previous paragraphs It is in visiting different stages and places in his life that Hughes continues his exploration of the relationship with Plath. The poem provocatively titled ‘Your Paris’ immediately implies a conflicting perspective in the second person possessive pronoun. Hughes sets up his and Plath’s view of Paris as oppositions. He presents himself positively as sensitive to the role of Paris in the then recent violence of World War II, which he reads in “each bullet scar in the Quai stonework”. Paris becomes their own battleground where their individual perspectives indicate a deeper conflict. Plath, in contrast to Hughes, is insensitive and can only see the “Impressionist paintings”, the writers who lived in Paris, “Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Henry Miller, Gertrude Stein”. His choice of writers critically emphasizes Plath’s narrow world-view, centred on America and indicated in the opening of the poem: “Your Paris, I thought, was American.” The inclusion of “I thought” in many ways tempers the exclusive effect of the statement but the criticism is pervasive. He implies that her view may be literary and artistic but it lacks sympathy for the people of Paris. “I kept my Paris from you.” There is clear animosity in this poem but Hughes perseveres in presenting himself as the one with insight, staring at “the stricken exposure of pavement”. His negative attitude to Plath is further developed in the metaphors of her expressions as she faces Paris (“your ecstacies ricocheted”, “a shatter of exclamations”, “your lingo / Always like an emergency burn-off”) suggesting that her ignorance of the past was as violent as the war that had marked so much of Paris. All of Hughes’ senses are heightened: he sees the controversial relationships formed in the Nazi period with “SS mannequins”; he tastes the coffee “still bitter / As acorns”; he smells “the stink of fear still hanging in the wardrobes” – all signs of Paris as a “post-war utility survivor”. In contrast, the sustained metaphor of the artist persists in reference to Plath with her “immaculate palette”. Despite these very antagonistic views of Plath resented in anger, the poem changes in tone as it progresses. Hughes becomes a dog who seeks out the “underground, the hide-out /That chamber” where Plath waited for her “stone god.” From here there is a classical allusion to the labyrinth, a motif that pervades many of the poems, implying the difficulty of coming near the centre of Plath but also the fear of her father, “the minotaur”. Suddenly we see a very different perspective of Plath, as Hughes excuses her “gushy burblings” as part of her “pain” and “torment” seen in her “flayed skin”. As her dog he is “loyal” and “happy to protect”. The poem is originally an attack, setting up Hughes’ perspective as superior to Plath’s, but we see Hughes turn the poem around to acknowledge the inner pain of Plath. He justifies the attack on Plath by placing blame for her psychological torment on her father, the “stone god”, the “minotaur”. Hughes has used strong oppositional imagery to track the breakdown of a relationship in a way that does not allow us to hear the other voice. That he is responding to a conflicting perspective about his relationship to Plath is clear in the defensive language used, but by silencing her voice and only offering his voice, we do not fully comprehend the whole argument. The meaning is further veiled in the poetic form, which favours a perspective by subtle and creative language selection. In the two poems ‘Fulbright Scholars’ and ‘Your Paris’, there 3 is also a clear structure which foregrounds the negative view of Plath and offers excuses near the end. In this way, Hughes further controls the voice we hear. This paragraph on the related text moves through the different ways perspective operates in the text: firstly through the point of view of the narrator, then the reader’s own understanding and finally through the author who makes the critical decisions about which character’s point of view to privilege Conclusion links the author, the text and perspective and ends with a comment about the way perspectives mediate reality Just like Hughes, Autumn Laing is dealing with the past and is controlling the perspective. She has been hounded by a biographer who wants her life story. “Let her struggle for her own truths”, she says, believing “our truths are written in our hearts and are not a currency of exchange.” This perspective is seen in the way she reacts to seeing Edith, the ex-wife of her lover Pat. A chance encounter has awakened a search for truth but what she finds is that expectations about perspectives are not always accurate. Even in her own past, her Uncle Matthew’s relationship with her as a young girl from the age of eleven is presented as positive and a source of love and yet as readers we can understand this differently as exploitation of a child. Her young adult years after her uncle’s death are confused and immoral, indicating that his effect on her was not positive. Presenting the text from one point of view can remove dissenting voices but Miller cleverly allows us space to read our own interpretation. He moves from the first person perspective to third person but even this is mediated by Autumn who is writing the biography and presents herself as she wants to be seen. Miller does, however, give space for different views by subtly inserting a letter from Pat, the opinions of others as reported by Autumn and the final word from the biographer who claims that Autumn has had to “distort my identity to serve her purposes”. We have to decide which perspective is valid. Hughes writes about a reality, about his wife, but is in fact the central character in his own grand narrative with a meandering plot that wanders through events in his married life from the perspective of time and in reaction to public criticism. As a novelist, Miller’s book takes real people and a relationship that was publicly criticized but crafts his own story. His narrator, Autumn, warns the reader that realism is “that most difficult of styles, filled as it is with intricacy and contradiction.” It is therefore through understanding different perspectives, especially conflicting perspectives, that we come to a realisation that truth is a mediated reality, a representation that is controlled by the person speaking. 4