Sylvia Plath`s secrets are hidden in plain sight

advertisement

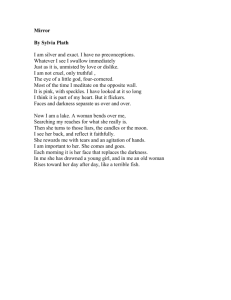

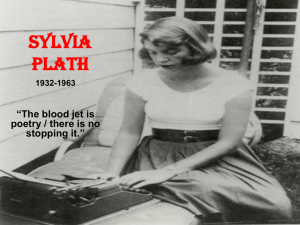

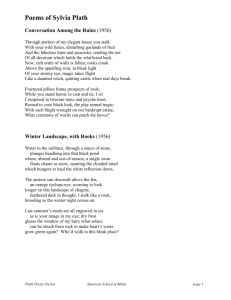

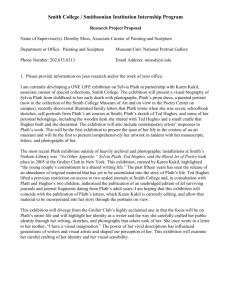

Sylvia Plath’s secrets are hidden in plain sight The poet's life has become so barnacled with argument that it is hard to discern the woman at the heart of the myth Jane Shilling Daily Telegraph, February 2 2013. In Mad Girl’s Love Song, his newly published account of the early life of Sylvia Plath, Andrew Wilson describes an incident from the poet’s schooldays. In 1947, when she was almost 15, Sylvia (already a meticulous diarist) recorded what happened on the way back from a sophomore icebreaker where she had spent the whole evening dancing with the same boy. As the teenaged couple wandered towards her home in the Boston suburb of Wellesley, her beau showering her with compliments about how sweet her hair smelt, and how charming she was, a pair of kittens began to frisk around their feet. But as they crossed the road, a speeding car raced toward them. Sylvia and her boyfriend were unhurt, but one of the kittens was killed. Sylvia scooped up the other and took it home, where she “released” it. The freight of symbolism in this vignette is almost comically disturbing. Everything we know about Plath – the meticulously constructed feminine persona, the compromised sexuality, the strange menace lurking within the familiar surroundings, the avid appetite for life juxtaposed with an equally urgent fascination with death – is contained in the vivid, almost kitsch, composition of teenagers, kittens and fast car. Or perhaps it would be more accurate to say, everything we think we know. It is almost 50 years since that bitterly cold February day when Sylvia Plath, aged 30, settled her small daughter and son in their cots with mugs of milk and a plate of bread and butter, sealed the door and window of the kitchen in her North London flat, then turned on the gas and lay down to die. In that time the story of her short life has become so barnacled with angry proprietorial argument; so encrusted with the projected wishes and desires of her would-be champions and interpreters, that it is hard to discern the authentic lineaments of the young woman at the heart of the myth; and harder still to read her writing with the clarity that it demands. There is a certain poetic symmetry in the fact that Plath, who was haunted by Shakespeare’s Tempest, and repeatedly used its imagery in her poetry, particularly when writing about her father, Otto, who died suddenly when she was eight years old, should herself have undergone a metamorphosis – a “sea-change”, as Ariel calls it in the play – from a poet at the height of her powers to sacrificial victim. Of course, Plath is not unique in having acquired a dense carapace of romantic myth after her death. The history of literature is littered with wayward geniuses whose talent was prematurely cut off. Yet something sets Plath apart from the melancholy roll-call of Keats, Shelley, Byron, Brooke, Rimbaud, Radiguet, Woolf, Sexton, and latterly the young playwright Sarah Kane. However powerful the myths of their deaths, these writers are still known mainly by their works. In Plath’s case, her writing began, soon after her death, to be relegated to a supporting role in a seductive, but intensely misleading, narrative of victimhood. As one of her many biographers, Jacqueline Rose, wrote: “When I ask students what they know of Plath, they almost invariably reply that she killed herself and was married to Ted Hughes. Occasionally they run these two snippets together as if the second were, in some mysterious and not wholly formulated way, related to the first; as if together they add up to something that leaves nothing more to be said. I watch this story shut down around her, clamping her writing into its hollow wooden frame. Death and marriage may have fed and fuelled her writing, but – posthumously at least – they cramp her style.” A more pressing argument for not writing a poet’s biography has seldom been articulated by a biographer. But the pickings of Plath’s life were too rich to resist: “For weeks, no dinner party from Hampstead to the Hamptons was complete without a discussion of it,” wrote the critic Elaine Showalter of Janet Malcolm’s The Silent Woman (1994). Malcolm, said Showalter, “takes arms against the hordes of biographers, journalists, feminists and sensation-seekers who have mercilessly raked over the ashes of Plath’s life, often blaming Hughes for his infidelity during Plath’s life and his iron control of her copyrights since her death. 'The pleasure of hearing ill of the dead is not a negligible one,’ she writes witheringly of their motives, 'but it pales before the pleasure of hearing ill of the living.’ ” Well, quite. And of course, Plath and Hughes themselves engaged diligently in their own separate and conjoined work of myth-making. “As artists… both were intent on finding voices for their unquiet, buried selves,” wrote their friend Al Alvarez, in the eloquent memoir of Sylvia with which he begins his study of suicide, The Savage God. And in the months before her death, Sylvia had found a new voice: “I kept telling myself I was the sort that could only write when peaceful at heart,” she wrote to her friend and fellow poet Ruth Fainlight. “But that is not so, the muse has come to live here, now Ted has gone.” Alvarez compares Plath’s last months with the “marvellous year” in which Keats produced almost all the poetry on which his reputation rests. Alone with her children, writing in the early mornings before they woke, “the poet and the poems become one.” This is the vital connection that somehow Plath’s biographers, however engaged or sensitive, can never quite make. At worst, a crude reading can result in an analysis such as that of Theodore Dalrymple, who excoriated Plath as “the patron saint of selfdramatisation” for such poems as “Lady Lazarus”, in which, he wrote, “the metaphorical use of the Holocaust measures not the scale of her suffering but of her self-pity”. More sympathetic critics still succumb to the seduction of reading Plath as though her writing were autobiography, rather than experience made transcendent. With a poet who drew so vividly on her own life for her art, the separation is not always easy to make. But even in her juvenilia, an assured clarity of tone is audible: “My love for you is more / athletic than a verb…” In the sudden blooming of her art just before her death there is an authority and a beautiful simplicity of vision that makes everyday objects – sheep, a bruise, a cut finger (“Dead white. / Then that red plush”) – resonant in a way that reaches far beyond mere anecdote. Half a century after her voice fell silent, perhaps it is time at last to seek the truth about Sylvia Plath in the most obvious place of all – her poetry: that tender, furious and utterly authentic record of a woman’s life.