The Hamlet and The Art of Revenge.doc

advertisement

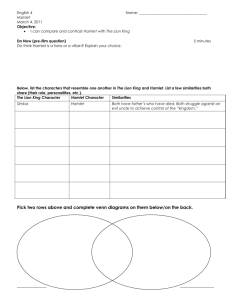

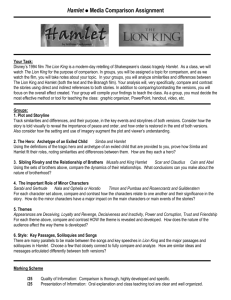

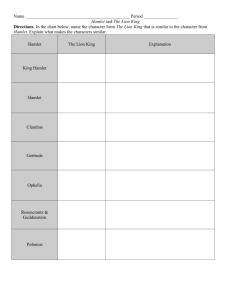

The Hamlet and The Art of Revenge: A Text Set of Analysis of the Play Within the Play Hamlet and The Art of Revenge: A Text Set of Analysis of the Play Within the Play What Is A Play Within A Play? The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark, or as it is more commonly called, Hamlet, is often referenced as one of the most powerful and influential tragedies in English literature. Written between 1599 and 1601, Hamlet is still a large part of the literary cannon and is one of Shakespeare’s most famous works. In Shakespeare’s time it was one of his most popular works as well as the most performed. Due to the breath and depth of it’s complex plot, it contains a story line that Arden Shakespeare writers Thompson and Taylor believe is rich enough for “seemingly endless retelling and adaptations by others” (Thompson and Taylor, 74). Hence, the play has been subject to many adaptations, retellings and revisions by various writers since its creation in the early 17th century. Two most prominent adaptations include Walt Disney The Lion King and Dragon Dynasty’s Legend of the Black Scorpion. While both works take a dramatic departure from the original source text that Shakespeare presents, analyzing the three works together proves beneficial as we consider the relationship that stories from the larger literary canon have to their inevitable adaptations. Film Adaptation Analysis: Where It Was and Where It’s Going As our text set considers the relationships between various adaptations and their original source text, it is important to bring film adaptation analysis into our discussion. In “Adaptation Studies at a Crossroads,” Thomas Leitch goes to great lengths to reframe the way that critics and readers alike might look at analyzing film adaptations. Leitch asserts that rather than viewing film adaptations as just recreations of original texts, viewers should accept “the possibility that literary adaptations are at once cinema and literature” (Leitch, 63). In other words, instead of going to a film and simply questioning how accurate the adaptation reflects the original work, viewers should consider the film adaptation literature in its own right and with its own purpose. Leitch views film adaptations as owning “duel citizenship” in the world of cinema as well as the world of literature (Leitch, 64). He desires the field to move out of the “notion that adaptations ought to be faithful to their ostensible source texts” (Leitch, 64). Leitch’s discussion becomes fruitful as we consider the deeper meanings of the three film adaptations of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. While Lawrence Oliver’s rendition of Hamlet stays close to the original source text, making it a good candidate for what Leitch describes as traditional film adaptation analysis, The Lion King and Legend of the Black Scorpion extend far beyond the plot that Shakespeare presents. This makes the latter two works not less significant, but rather good works to consider as Leitch and others reinvent the field of film adaptation analysis. Standing on the shoulders of fellow film adaption scholar Julie Sanders, Leitch discusses the dichotomy that Sanders presents between film adaptation and film appropriation. Unlike adaptation, which “signals a relationship with an informing source text or original,” film appropriation “frequently affects a more decisive journey away from the informing source into a wholly new cultural product and domain that may or may not involve a generic shift” (Sanders, 26). Thus, according to Sanders, The Lion King and Legend of the Black Scorpion are not film adaptations, but rather film appropriations as the viewer leaves Shakespeare’s world of Elizabethan society and enters Walt Disney’s world of animation and the strict hierarchal world of imperialistic China. With this distinction in mind, of our text set will hold greater meaning, as we are not solely concerned with how closely a work replicates Shakespeare, but rather how the work becomes a comment on the culture it represents. Film appropriation analysis forces the viewer to employ his or her own knowledge of culture to fully understand the text under consideration. When considering each work in our text set through this lens, the viewer becomes more aware of not only the significance of Hamlet, The Lion King and Legend of the Black Scorpion, but also the significance of cultural differences as each protagonist explores revenge and the usurping of his rightful throne. While the dichotomy that Sanders presents to her readers seems to be a black and white distinction, we would like to assert that there are many works that must be analyzed under the old tenets of film adaptation as well as the new rubric of film appropriation. While The Lion King and Legend of the Black Scorpion are both departures from the original source text of Hamlet, they have scenes that are directly taken from Shakespeare’s original work. Thus, it is not enough to stay strictly close to the source text in analysis nor is it enough to disregard the source text entirely. To explore the full meaning of each work, analysts must both consult the source text as well as critique the work in its own right. The Play Within the Play: Recreation of and Departure from Shakespeare The scene where Hamlet demonstrates his knowledge of how his uncle was murdered by presenting a play for Claudius is present in all three of our texts. While it is taken directly from Shakespeare’s original work, the details of how each scene plays out vary. However, each work uses the scene to depict the past action that the protagonist wishes to avenge by the end of the narrative. Thus, the play within the play, as it is referenced by literary critics, becomes the vehicle for the revenge that drives the plot forward. As we further analyze these scenes, Saunders appropriation paradigm reveals reflections of the “wholly new cultural product” that each text presents. What Is A Play Within A Play? One of Shakespeare’s best-known literary devices, the play within the play is used to tell one story while another story is already in action. Sigmund Freud devoted a significant portion of his career to the topic of dreams and alternative realities. In one of his greater works, Freud comments at length about “dreams within dreams.” Scholars have continually used this analysis in connection with the literary device of a play within the play. He writes: What is dreamt in a dream after waking from the 'dream within a dream' is what the dream wish seeks to put in the place of an obliterated reality. It is safe to suppose, therefore, that what has been 'dreamt' in the dream is a representation of the reality, the true recollection, while the continuation of the dream, on the contrary, merely represents what the dreamer wishes. To include something in a 'dream within a dream' is thus equivalent to wishing that the thing described as a dream had never happened. Following Freud, we can see that the play within the play is much like an awakened dream. If the dream within a dream represents a wish to erase the dream itself, a wish that the "dream has never happened," then the play within the play represents a desire to erase the events of the past. This holds true in Shakespeare’s Hamlet as the prince deeply wishes that his father were still alive. Similarly in The Lion King and Legend of the Black Scorpion each son remembers his father’s death with disdain and regret. Thus, the play within the play is a direct illustration of a past act that the protagonist needs to come to terms with. The Play Within the Play and Revenge For our purposes, the play within the play holds great significance as it serves as a vehicle for Hamlet's desire for revenge as acted out in front of his father's murderer. In Hamlet, the play within the play allows the prince to reenact the death of his father in front of his father’s murderer, Claudius . Hamlet wishes to provoke his uncle as well as make clear that he knows the truth of his father’s death. In The Lion King, it is not until Simba is on the brink of death, holding on for his life, that Scar confesses to Mufassa’s murder. The scene becomes nearly identical to the moment in which Scar murders Mufassa. In this way, it becomes a play within the play, a re- enac tment of the father’s death, much like the plays put on by the protagonists in the other works. Finally in Legend of the Black Scorpion, the play is a dramatic dance between two characters, one representing the king and the other his murderous brother. For Hamlet, Prince Wu Laung, and Simba, the only action that will effectively put their fathers’ deaths in the past is to reclaim the throne by killing their murderous uncles. While each protagonist arrives at this conclusion differently, the “obliterated reality” that they seek consists of a life without their uncle and a life in which they take rightful ownership over the throne. The Play Within the Play in Hamlet Shakespeare titled the play within the play that takes place in Act III, Scene ii of Hamlet “The Mousetrap.” By producing a play for his uncle Claudius, Hamlet hopes to “catch the conscience of the king”—to confirm his own suspicions that Claudius did, in fact, poison Hamlet senior and to let Claudius know that Hamlet is aware of his uncle’s fratricide (Doebler, 50). As the play is about to begin, Hamlet remarks, "look you, how cheerfully my/ mother looks, and my father died within these two hours" (III, ii, 115). Then the play about a murder in Vienna of a Viennese king, Gonzago, begins. A King and Queen embrace lovingly. Remarking that he is getting old and frail, the player Queen replies that she would never remarry, saying "None wed the second but who killed the first" (III, ii, 169). The King lies down to sleep and the Queen exits. Then, another man enters and pours poison into the sleeping King's ear. At this reenactment of the murder, Claudius stops the play and rushes out of the room in a fit of rage, which Hamlet sees as indicative of his uncle’s guilt. How the Play Within the Play Drives Hamlet’s Revenge Previously, while contemplating producing the play, Hamlet says, “I’ll have these players/ Play something like the murder of my father/ Before mine uncle. I’ll observe his looks,/ I’ll tent him to the quick. If he but belch,/ I’ll know my course” (Doebler, 50). Here Hamlet clearly lays out the relationship between this play within a play and revenge. The revenge is directly initiated by Claudius’s reaction to Hamlet’s “Mousetrap.” And, as Freud would suggest, it is through the play that Hamlet begins to come to terms with the murder of his father. It is after the play within the play that Hamlet’s madness that has been developing for some time now takes on a very definite purpose. He says, “That I essentially am not in madness/ But mad in craft” (III, iv, 209-210). Now that he has confirmation of Claudius’s guilt, he is utterly consumed with the idea of revenge; his madness serves as a cover for the vengeful thoughts that fill his head. Hamlet’s plans for revenge take an unexpected turn when Laertes challenges Hamlet to a duel. During this duel, not only do Hamlet, Claudius, and Laertes all die of the same poisoned sword, but Hamlet’s mother, Gertrude, falls dead upon drinking from a poisoned chalice. Thus Hamlet’s plan for revenge certainly does not play out the way he intended. Further, it is the obsession with revenge, incited by the play within the play, that ultimately leads to the death of so many—by killing Laertes’ father and inciting Laertes’ anger, Hamlet directly and indirectly causes the death of Laertes, Laertes’ father, the Queen, and ultimately, himself (in addition to Claudius, as he had planned). Critic John Doebler suggests that the word “mousetrap,” the title which Hamlet assigns to the play, would carry “rich iconographical associations” for the Renaissance audiences that a contemporary reader would likely miss (Doebler, 162). Given the commonplace nature of this symbol in the Renaissance, Doebler asserts that the “brief mention of the play’s title itself” can be seen as “a symbolic microcosm communicating to the audience much of the elaborate irony on which the whole dramatic action of Hamlet pivots” (Doebler, 162). Doebler cites the myriad of connotations associated with mice including gluttony, corruption of all they touch, charges of uncleanliness in the Bible, and the Augustinian conception of the cross as a mousetrap on which the devil was ensnared and subsequently caused his downfall. The Augustinian conception of the mousetrap, which would have been very familiar to Shakespeare’s contemporaries, dovetails perfectly with the outcome of Hamlet’s plan for revenge as “when the trap is set the devil snaps at the bait; the mouse is caught; but he is caught by one who must himself die to defeat him fully.” Hamlet’s death parallels Jesus’ and “results in tragic resurrection, in the sense that he has died while saving the kingdom for mankind” (Doebler, 169). Thus, by conflating Claudius with a mouse and the play with the initial trap in Hamlet’s plan of revenge, Shakespeare uses the play as a critical device in conveying the overarching meaning of the entire play to the audience. The Lion King Simba = Hamlet Mufasa = Old Hamlet Scar = Claudius The Lion King does not contain the same obvious “play within a play” that appears in The Legend of the Black Scorpion and Hamlet. However, the recreation of Mufassa’s death plays the same essential role in inciting Simba’s desire for revenge. Simba returns to pride rock, not to avenge his father’s murder, but rather to take his rightful place as king, to fulfill his destiny and do the moral and just thing. He still feels remorse and responsibility for his father’s death. It is not until Simba is on the brink of death, holding on for his life, that Scar confesses to Mufassa’s murder. The scene becomes nearly identical to the moment in which Scar murders Mufassa. In this way, it becomes a play, a reenactment of the father’s death. Unlike Hamlet and The Legend of the Black Scorpion, Simba is not aware of Scar’s crime until this moment. This final “play within the play” scene is essential in serving as the catalyst for revenge. The antagonist, not the protagonist, puts on the “play” in The Lion King. Scar forces Simba into revenging Mufasa's death by putting Simba's own life at risk. Until this moment, no revenge would have been sought. Ultimately, by shifting the instigator of revenge from Hamlet or Simba, as is traditional, to Claudius or Scar, the Disney film is attempting to prevent the audience from perceiving the protagonist in a negative light. Simba's motives for returning to Pride Rock remain pure; he has come back to fulfill his destiny as king, not to murder his uncle. By laying out the story in this way, Disney maintains the distinct line between good and evil. Walt Disney’s films obviously target a very specific audience. Nearly all of his animated films are meant to appeal to audiences within their childhood years, instilling morals and virtues that Disney deemed important. In 1937 both Cosmopolitan and Karl W. Bigelow referred to Walt Disney as "the Aesop of the twentieth century" (Watts 144). Disney was considered a moralist, an educator, a child psychologist and even a theologian. His films were praised for their positive impact on young viewers by experts on child raising and pyschology (Watts 145). The Lion King was released in 1994 during what is considered the Disney Renaissance (1989-1999), a time when Disney was once again creating successful films, most of which were based on fairy tales and other stories meant to teach moral virtues. The Lion King, while not a fairy tale, is modeled after several stories including Hamlet. Here we see how an analytical lens like appropriation can yield insights; not only does The Lion King refashion Hamlet, it borrows from fairy tales and Disney-inspired moral codes to create a film that embodies a new set of cultural values. Walt Disney utilizes the play within the play to create a morally acceptable ending, one in which the protagonist is without a doubt a pure hero. When Simba confronts Scar in their final scene, Simba tells Scar that he “doesn’t deserve to live” (The Lion King). However, Simba will not kill his Uncle; Disney will not sully the protagonist. When Scar asks if he will kill him, Simba replys, “No Scar, I’m not like you” (The Lion King). Here Disney is protecting the protagonist to propagate a good-protagonist message. Simba will not continue the cycle of deaths; rather, he tells Scar to “run, run away... and never return” (The Lion King). Here Simba is showing great mercy, a quality of a good king, and in turn Disney is pushing this same message of the desirability of mercy and nonviolence onto the audience. It is essential to Disney to distinguish good from evil, the dark from the light. Utilizing Jungian archetypes, Scar is symbolized as the shadow archetype, and is inherently evil, while Simba embodies the light. This is most evident in their final battle. Where the two lions clash and dark battles light. In this epic scene, the battle between good and evil, good must, and will, prevail. To appeal to and condition the audience that Disney targets, good must always defeat evil, while maintaining the moral virtues of the protagonist. This need to maintain the purity of the protagonist is most evident in the fact that Simba does not execute the final revenge. It is in fact, the hyenas who kill Scar. This prevents a young audience from associating the protagonist with any act that could be perceived as evil. In this way his revenge becomes justified, and our protagonist is kept in an amiable light. Ultimately the “play within the play” in The Lion King serves as both the catalyst for revenge, but also a measure to preserve the moral structure of the protagonist and the movie as a whole. The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life. By Steven Watts. (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1997 The Legend of the Black Scorpion Prince Wu Luan = Hamlet Emperor Li = Claudius Empress Wan = Gertrude The Legend of the Black Scorpion is an adaptation of Hamlet set in China at the end of the Tang Dynasty in 907 A.D. The story follows many of the same lines of Shakespeare's original script. Prince Wu Luan is the son of a poisoned emperor. Emperor Li, Wu Luan's uncle, takes the throne and marries Empress Wan, the old emperor's wife. The Prince's love interest commits suicide. Before it's over, Wu Luan witnesses the death of his uncle, bringing closure to his quest for to avenge his father's death, right before meeting his own end. However, despite all of its similarities to the original Hamlet, Black Scorpion features key variations that remind the viewer that this story takes place in an entirely new world. Li and Wan bear remarkable similarities to two transcendent emperors from Chinese history. Li's story is reminiscent of Zhu Quanzhong's, the man responsible for the end of the Tang Dynasty, which had lasted for nearly 300 years. Wan's tale follows that of Wu Zetian, the only woman to ever become emperor of China. But, because these two people are from different times and in order to fit into the framework of Shakespeare's Hamlet, Black Scorpion takes some liberties and alters historical events enough to make the movie work. Empress Wan is a former, but still possible, love interest of Wu Luan, not his mother. This sets up a multi-level rivalry between the Prince and his uncle, the emperor. Not only is there disagreement about whether Li killed Wu Luan's father, but Li's new wife has romantic and sexual feelings for Wu Luan. Zetian entered the Chinese court as a lesser wife of then Emperor Gaozong, not considered an empress. She began her rise to power by killing her own daughter and blaming it on the current empress, using the episode to usurp the empress and rise to power. In 655, the emperor suffered a stroke and Wu started giving orders to state councilors. In 675, Wu's son suddenly died when he tried to assert his authority and take the throne. Five years later, the next heir apparent was accused by Wu of plotting a rebellion, banished and forced to commit suicide. In 683, Emperor Gaozong died and his oldest son took the throne. However, six weeks later, Wu installed the younger 12-year-old son as emperor. In 690, she forced him out of power and became the first female Chinese emperor. She ruled for 15 years before palace officials forced her out. Her life is full of deceit, no different than Wan's. In Black Scorpion, Wan deceives Li so he will trust her, telling him he pleases her sexually better than her previous husband ever did, making it easier for her to trick him in the end. Zhu Quanzhong was a military governor serving underneath Emperor Zhaozong in the early 10th century. But in 904 he organized the murder of the emperor and most of his family and installed Zhaozong's 13year-old son as the new emperor. In 907, he executed anyone still loyal to Zhaozong and forced the 13year-old emperor to give up the throne. This signaled the end of the Tang Dyansty. Five years later, in 912, Quanzhong, then emperor, was murdered by his son, Zhu Yougui. Soon thereafter, Yougui was killed by his brother, Zhu Youzhen, giving the throne to Quanzhong's nephew. The scene in The Legend of the Black Scorpion that reveals the inner feelings of the characters and forces the action takes place when Wu Luan presents a play at the coronation of Empress Wan, a play within a play very similar to what we find in Hamlet. During the play, Wu Luan wears a mask. He believes that wearing a mask during a performance allows for the actor to convey "complex and hidden emotions," rather than those that are just on the surface. It puts the focus of the audience on the actions of the play rather than on the faces of the actors. The play is a dramatic dance between two characters, one representing Li and the other Wu Luan's father. Wu Luan beats a drum on the ground behind the drama as the the characters move. It ends with the character Li blowing poison into the ear of the other, killing him while he lies on the ground, seemingly asleep. The poison is the same used in the murder of Wu Luan's father, the poison of a black scorpion. In Shakespeare's Hamlet, the play within the play is presented in much the same way, as the murder is reenacted. During the play in Black Scorpion, the camera flashes back to Li's face three times, the third one immediately following the blowing of the poison into the ear. On the third instance, his hand is shown as he nervously brings it to rest against his leg right as the poison is about to be blown. This is taken as the realization that the uncle realizes that Wu Luan knows of his deed. The Emperor responds by appointing Wu Luan as ambassador to a far-away province and sends him away. Wan's prominence in this adaptation of Hamlet is shown again as she sends General Yin, the army general, to bring Wu Luan back from the guards that are escorting him to his new post. The guards had meant to kill Wu Luan, but Wan saves him. These events follow the text of Hamlet closely. Claudius sends Hamlet away to England in a plot to kill him. However, in Shakespeare's text, Hamlet decides on his own to return and take revenge on Claudius. In Black Scorpion, Wu Luan must be rescued, suggesting the stronger role in the film for the female Wan. Outright accusation of murder does not come until Wu Luan returns on the night of a banquet where the Emperor is to be poisoned. The banquet is being held by the emperor in an attempt to gain the admiration of the public. Wu Luan arrives after his rescue, accuses Li of murdering his father "like a coward," and challenges him to a duel as Li picks up the cup of wine. The Emperor knows the wine is poisoned because it has already killed Quin Nu, Wu Luan's young lover. Li realizes his whole house is against him. His wife doesn't love him. His nephew is out for revenge. He fears the spirit of his brother and rather than fight in dishonor, drinks the cup willingly and accepts death. Wu Luan dies from a poisoned blade, the same as Hamlet, as he tries to protect Wan from General Yin, who was trying to kill her because he did not support her cause. Wan is then shown happily smiling as she realizes that there is now nothing standing in the way of her becoming emperor. However, as soon as the smile crosses her face, a dagger comes flying from the background and pierces her through the heart. Her killer is never shown, but her death is symbolic in that is represents the end of corruption in the royal family. By the end of Black Scorpion, Wu Luan is represented much the same as Hamlet, as a hero who fought for the honor of his father's name and then died because of the greed of others. Conclusion A relatively new field of study, film adaptation analysis has much room to grow and expand as it finds its identity within the world of academia. When it comes to the text set analysis of Hamlet, The Lion King, and Legend of the Black Scorpion, it is apparent that the age old approach of strict analysis of an adaptation's relationship to an original source text is not enough to understand the complexities of each new work. Conversely, one cannot abandon Shakespeare's original work when considering the richness of each subsequent film. Thus it becomes important to understand each film as a work of art in its own right with its own cultural context as well as a comment on the original source text and the original themes explored by Shakespeare. Shakespeare uses the play within the play as an essential device as he tries to convey the overarching meaning of Hamlet's ultimate revenege to the audience. Subtle cultural references in the original text help to further elucidate his intentions. Disney employs Hamlet as the backbone to The Lion King. Utilizing the core story of Hamlet, and altering it to create a "happily ever after" ending, Walt Disney creates a story that stands independent of the original text. The Legend of the Black Scorpion follows the original text of Shakespeare's Hamlet closely in the way the story is presented and carried out. However, The Legend of the Black Scorpion differs in its characterization of the female characters, most notably Empress Wan, to make the movie more historically accurate in terms of Chinese history. The Legend of the Black Scorpion takes real people and events from the Chinese past and alters them enough to fit into the framework of an adaptation of Hamlet. When considering all these changes and relationships together, the full signifiicance of Hamlet and it's relationship to its film adaptations is realized and the field of field adaptation analysis can be taken to a new level. Bibliography Doebler, John. "The Play Within the Play: the Muscipula Diaboli in Hamlet." Shakespeare Quarterly 23 (1972): 161-69. JSTOR. Web. 7 Feb. 2010. Leitch, Thomas. "Adaptation Studies at a Crossroads." Adaptation 1.1 (2008): 63-77. Print. Shakespeare, William. "The Arden Shakespeare Hamlet. Edited by Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor." London: Thomson Learning (2006). Print. Watts, Steven. "The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life." Columbia: University of Missouri Press (1997). Print. Image citations: "Laurence Oliver as Hamlet." 8 Jun. 2009. 1 March. 2010 <http://colindickey.wordpress.com/2009/06/>. Lion King Image Archive "Simba on Pride Rock." 1 Feb. 2010. 1 March. 2010 <http://www.lionking.org/imgarchive/?Miscellaneous_Images+hi> Rohrbach Library "William Shakespeare 1" April 2009. 1 March. 2010 <http://rohrbachlibrary.wordpress.com/2009/04/> Public Forum Institutue. "Walt Disney."1 March. 2010 < http://www.publicforuminstitute.org/nde/news/innovators/disney.htm> Movieberry. "Hamlet Movie Poster"1 March. 2010 < http://www.movieberry.com/hamlet_70/> Lion King Image Archive "Lion King Video Cover." 1 Feb. 2010. 1 March. 2010 <http://www.lionking.org/imgarchive/?Miscellaneous_Images+hi> Starpulse "Legend of the Black Scorpion Video Cover" 10 Feb. 2008. 1 March. 2010 <http://www.starpulse.com/news/index.php/2008/02/10/legend_of_the_black_scorpion_arrives_on__26> Ronald Grant Archive "Hamlet with Sword." 1 March. 2010 <http://www.guardian.co.uk/arts/gallery/2007/sep/11/hamlets?picture=330719285> Lion King Image Archive "Simba and Scar Fight." 1 Feb. 2010. 1 March. 2010 <http://www.lionking.org/imgarchive/?Miscellaneous_Images+hi> Universal Pictures Company, Inc. "Hamlet Seated with Claudius." 1953. 1 March. 2010 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/590186/theatre> Lion King Image Archive "Scar Attacks Simba." 1 Feb. 2010. 1 March. 2010 <http://www.lionking.org/imgarchive/?Miscellaneous_Images+hi> Lion King Image Archive "Scar's Little Secret." 1 Feb. 2010. 1 March. 2010 <http://www.lionking.org/imgarchive/?Miscellaneous_Images+hi> "Wu Zitan" 28 Feb. 2010. 1 March. 2010 <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wu_Zetian> "Empress Wan" 1. March. 2010 < http://www.chud.com/articles/articles/13736/1/CONTEST-LEGEND-OFTHE-BLACK-SCORPION-DVD/Page1.html>