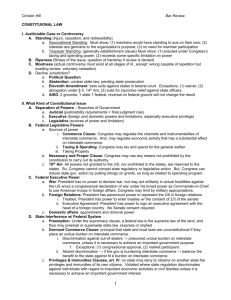

Word - Washington University School of Law

advertisement