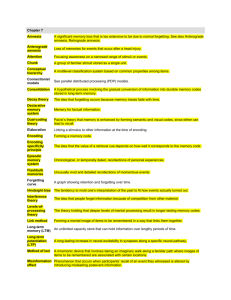

Chapter 9: Memory The Phenomenon of Memory Information

advertisement

Chapter 9: Memory The Phenomenon of Memory Information Processing Memory is the persistence of learning over time. Psychologists have proposed several information-processing models of memory. We will use the influential three-stage processing model, which suggests that we (1) register fleeting sensory memories, some of which are (2) processed into on-screen short-term or working memories, a tiny fraction of which are (3) encoded for long-term memory and, possibly, later retrieval. Encoding: Getting Information In How and What We Encode Some types of information, notably information concerning space, time, and frequency, we encode mostly automatically. Other types of information, including much of our processing of meaning, imagery, and organization, require effort. Mnemonic devices depend on the memorability of visual images and of information that is organized into chunks. Organizing information into chunks and hierarchies also aids memory. Storage: Retaining Information Sensory Memory Information first enters the memory system through the senses. We register and briefly store visual images via iconic memory and sounds via echoic memory. Working/Short-Term and Long-Term Memory Our short-term memory span for information just presented is limited—a seconds-long retention of up to about seven items, depending on the information and how it is presented. Our capacity for storing information permanently in long-term memory is essentially unlimited. Storing Memories in the Brain The search for the physical basis of memory has recently focused on the synapses and their neurotransmitters; on the long-term potentiation of brain circuits, such as those running through the hippocampus; and on the effects of stress hormones on memory. Studies of people with brain damage reveal that we have two types of memory operating together—explicit (declarative) memories processed by the hippocampus, and implicit (procedural) memories processed by the cerebellum and the amygdala. Retrieval: Getting Information Out Retrieval Cues To be remembered, information must be encoded, stored, and then retrieved. Memory is recall, recognition, and relearning. With the aid of associations (cues) that prime the memory, we retrieve the information we want to remember. Cues sometimes come from returning to the original context. We use our senses as cues-a taste, smell, or sight may evoke us to recall a memory. Mood affects memory, too. While in a good or bad mood, we tend to retrieve memories congruent with that mood. Forgetting Encoding Failure One explanation of forgetting is that we fail to encode information for entry into our memory system. Without effortful processing, we never notice or process much of what we sense. Age affects encoding efficiency, which explains age-related decline. Storage Decay Memories may also fade after storage—often rapidly at first, and then leveling off. This is the basis for one of psychology’s laws, the forgetting curve. Retrieval Failure Forgetting also results from retrieval failure. Retrieval-related forgetting may be caused by a lack of retrieval cues, by proactive or retroactive interference, or even, said Freud, by motivated forgetting. Memory Construction Misinformation and Imagination Effects Memories are not stored as exact copies, and they certainly are not retrieved as such. Rather, we construct our memories, using both stored and new information. Thus, when child or adult eyewitnesses are subtly exposed to misinformation after an event, they often believe they saw the misleading details as part of the event. Source Amnesia People also exhibit source amnesia, by attributing something heard, read, or imagined to a wrong source. Because false memories feel like true memories and are equally durable, sincerity need not signify reality. Discerning True and False Memories Determining the validity of a memory is difficult. A false memory may feel real and it may be persistent. Interviewers may ask leading questions, contributing to the misinformation effect. True memories tend to be more detailed than imagined ones, which tend to be the gist of the meaning and feelings associated with an event. Children’s Eyewitness Recall Children are suggestible and, if asked leading questions, can report false events. On the other hand, if children are interviewed using the cognitive interview technique in developmentally-appropriate language, recalled memories can be accurate. Repressed or Constructed Memories of Abuse? Memory researchers are especially suspicious of claims of long-repressed memories of sexual abuse, UFO abduction, or other traumas "recovered" with the aid of a therapist or suggestive book. More than we once supposed, incest and abuse happen. But unless the victim was a child too young to remember any early experiences, such traumas are usually remembered vividly, not banished into an active but inaccessible unconscious. Improving Memory The psychology of memory suggests concrete strategies for improving memory. These include spaced study; active rehearsal; encoding of well-organized, vivid, meaningful associations; mnemonic techniques; returning to contexts and moods that are rich with associations; recording memories before misinformation can corrupt them; minimizing interference; and self-testing and rehearsal.