Discovering the Human Spark - Alumni

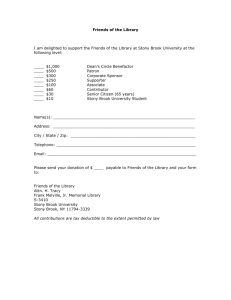

advertisement