Liability of Multiple Defendants

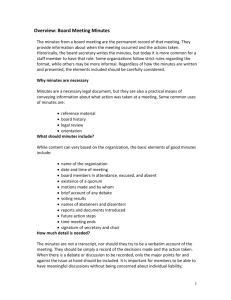

advertisement