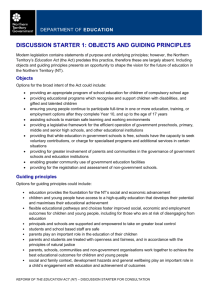

Six guiding principles for evaluating mode

advertisement