by Rajiv Trivedi and Terence Tuhinanshu

advertisement

Proceedings

International Seminar on ‘Creating & Teaching Music Patterns’

OmeSwarlipi: Communicating Complex Music Patterns

Dr. Rajiv Trivedi, Madhukali, Bhopal and Terence Tuhinanshu, Designer &

Developer, Philadelphia

Page | 261

Abstract

Indian Classical Music, employing microtonal units blended with numerous rhythm patterns, is

expressed in Raga compositions. These compositions, unlike the western compositions, are proximate

to software, being relational and open ended rather than fixed in (note) sound. Development of

instrumental style independent of vocal music added to requirement of symbols for embellishments.

The reluctance to use, if not rejection of, existing notation system, grew as publishing switched to

computers.

After development of an editing software for Bhatkhande annotation with Dr. Ragini Trivedi, which

expressed all requisite marks through key-strokes, the impracticability of this system became

apparent even as some volumes (three published, one in press) using this software were published.

To address the needs of a digital user, a symbol-based notation system – OmeSwarlipi, invented by

Dr. Ragini Trivedi – did away with lower arch notations for beats and phrases by using Paluskar’s

convention of keeping all notes of a Matra within main and sub division-marks (Matra&Vibhag). The

starting Matra of composition is indicated with corresponding number below it, eliminating need for

creation of grid (16-beat or 14-beat). The mizrabBol-s accessible through single key-strokes placed

just below the notes provide easy visibility. The problem of mono-spacing of characters was resolved

even in software for Bhatkhande by creation of single characters for ‘नी, म॑’ etcetera, yet using Kan

affects readability and disturbs spacing.

Omescribe was developed as a portal (http://www.omescribe.com/) for providing open and free use

of the music-script, in which, input from user’s key-board get converted into symbols of OmeSwarlipi.

There exist several problems like desk-top-publishing software compatibility, support of ligatures on

browsers, etcetera. With twelve main notes, several keys like ‘l’, ‘u’, ‘q’, ‘{‘, ‘}’, ‘\’ are in use for

various expressions. To balance unique single or two key-stroke combinations with intuitive layout of

software poses challenge with each resolution.

This paper would identify circumstances, manner of development, problems (solved and remaining),

of (1) OmeSwarlipi and (2) delivery of OmeSwarlipi script through Omescribe portal.

Keywords: Music Notation, BhatkhandeSwarankanPaddhati, OmeSwarlipi, Omescribe, Digital Music Notation

System, Font delivery, Ligatures, UX Design

Introduction

As computers play an ever greater role in education and everyday life, the need for a computer

based solution for writing and representing musical compositions becomes paramount. After a long

history of oral tradition, the most popular of Indian music writing traditions is the Bhatkhande script

(Widdess 1996), invented by Pt. Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande in the early twentieth century. But

does it satisfy the needs of modern complex music patterns? What are the issues that writers of

music face today, and what can be done to address them?

In this paper we first discuss the requirements of a tool that needs to convey the specific patterns of

Indian music. Then talk of the needs of modern musicians and how existing techniques are

Department of Instrumental Music, Rabindra Bharati University | 16-18 December, 2013

Proceedings

International Seminar on ‘Creating & Teaching Music Patterns’

stretched. We outline the design of

OmeSwarlipi, a font developed for the

script of the same name created by Dr.

Ragini Trivedi, and explain how it satisfies

these requirements. Finally we lay the

foundation of Omescribe, an online Page | 262

service that promises to solve other issues

faced by those who would write music

today.

Requirements

Observing the evolution and adoption of

previous attempts at musical notation

from different perspectives, we can begin

to identify features which make a script

usable. For the purpose of this analysis,

we consider three perspectives: the

reader, the writer, and the medium.

Reader

The reader is the ultimate audience of

written music, even as they transform the

text into actual music for a new audience.

For a reader to read music, it is imperative

that they understand the rules of the

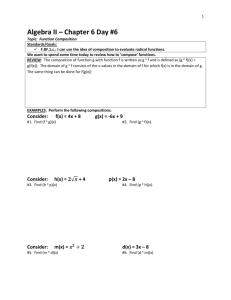

Figure 1 Comparison of Bhatkhande (left) and Paluskar (right)

script. Thus a script should be easily

(Trivedi, स्वरलऱपऩअन्कन: साववभौलमकताअथवाऩूर्ावलभव्यक्तत2008)

understandable. One of the reasons both

Bhatkhande and Paluskar scripts were

adopted abundantly was that they used local scripts to represent the notes – Devanagari in most

Hindi-speaking communities, but also Kannada in the South, and Roman by non-Hindi speaking

peoples. However, Bhathkhande’s script uses fewer new symbols, making it easier to learn than

Paluskar’s. For example, Bhatkhande’s script uses the same symbol to represent lower and upper

octaves (a single dot), just in different positions (below the note for lower octave, above for upper

octave), whereas Paluskar uses a dot below for lower octave and a vertical bar above for upper

octave.

Consistency is another desirable trait. A written phrase should not be ambivalent, but clear and

definite in its meaning and intent. The style for writing similar symbols should be alike, while the

style of writing dissimilar symbols should be distinct, and these rules should be applied and followed

consistently. Bhatkhande’s script is better at this than Paluskar’s, especially in multi-beat

representation where Bhatkhande uses one convex arc below the participating notes, and Paluskar

uses five different symbols, some of which (like the hollow circle) are used elsewhere for different

purposes. This is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

All these features help the reader comprehend quickly. However, there are also techniques that are

used to improve the mechanical aspect of reading. Both Bhatkhande and Paluskar scripts have

vertical parity in which one line with musical notes is followed right below by vocal lyrics or by

stroke notation (MizrabBol-s), and then by beat markings. This allows one to capture a complete

Department of Instrumental Music, Rabindra Bharati University | 16-18 December, 2013

Proceedings

International Seminar on ‘Creating & Teaching Music Patterns’

understanding of music in one movement of the eye. This vertical parity is demonstrated by a

sample composition shown in Figure2.

Paluskar script does have one advantage over Bhatkhande – its beat markings. In Paluskar script the

explicit number of the beat is written, whereas Bhatkhande uses a beat-sectioning approach. This

allows simpler compositions to be represented in a familiar pattern, but complex compositions and

Page | 263

those that start at uncommon beats harder to represent in Bhatkhande.

Thus, the primary factors of usability for the reader are – ease of understanding, consistency of

style, and harmonious representation.

Writer

While the act of reading is performed in isolation, the act of writing is inevitably accompanied by the

act of reading. Thus many of the reader’s goals also apply to the writer. However the writer needs

more, and here we discuss some of these requirements.

Figure 2 Sthai in Teen Tal, Raga Bilawal (Trivedi, रागपवबोध: लमश्रबानी2012)

The primary concern of the writer is expressiveness. The script must be able to accurately express

content, and thus it should have features that support the various aspects of the subject. Both

Bhatkhande and Paluskar scripts provide features to represent notes, beats, divisions, meend and so

on.

In addition, the expression should also be coherent and idiomatic so that the spirit of content can be

expressed just as well as the body. Bhatkhande’s use of convex arcs to represent multi-beat notes is

Department of Instrumental Music, Rabindra Bharati University | 16-18 December, 2013

Proceedings

International Seminar on ‘Creating & Teaching Music Patterns’

more expressive than Paluskar’s vulgar fractions1 because they visually group notes. They help

visually convey the music in a more intuitive manner that can give the reader a sense of the music

without having to read it.

Another important feature is efficiency, or the amount of effort it takes to write. Because

Bhatkhande used fewer characters than Paluskar, one could write quicker using it. Thus, on paper at

Page | 264

least, Bhatkhande had an advantage.

An important functional requirement for a writer is transferability, or the ease with which they can

use multiple media using their script. One of the most important reasons of Bhatkhande’s

prevalence is that it uses a set of characters much closer to Hindi then Paluskar’s, thus making it

easier to print on a metal press which is already equipped with Hindi characters. Thus it was easier

to transfer Bhatkhande to print than it was Paluskar, and it held an advantage in print as well.

Medium

Finally, the medium itself should satisfy certain requirements for it to be a viable choice for readers

and writers. It is important for a medium to be consistent and reproducible for correct propagation

of information. It should also be adaptable, and be able to exist on a number of platforms. Finally it

should be concise, having a minimal informational overhead apart from the content it carries for its

own purposes.

Limitations

The existing scripts were designed for a certain era with the requirements of the time in mind. As

music has evolved, this new era needs a new script to sustain it. There are now techniques,

Misrabani being the most prominent of them, that focus on the instrumental aspect of music. This

requires extensive use of stroke notation (MizrabBol-s), compositions that start at uncommon beats,

and degrees of complexity that would not find full expression in a Guru-Shishya manner of oral

tradition in which the teacher would sing to the student, leave room for improvisation, and not

write everything down explicitly.

But Bhatkhande’s script, for all its ingenuity, is not without its limitations. For example, it is not a

compact script – it takes a lot of visual space for one composition due to the beat structure that it

imposes. This is demonstrated in Figure 3. Traditionally written in Devanagari, it is difficult to learn

for non-Hindi speakers. When written in other scripts, the compositions become inconsistent and

non-transferable, locked in their own locales.

1

Vulgar Fraction, also known as a diagonal fraction (Strizver 2006), is a typographic term to describe a single

glyph that contains a whole number as a numerator and denominator, such as ½ or ¾. For details see (Quinion

2007)

Department of Instrumental Music, Rabindra Bharati University | 16-18 December, 2013

Proceedings

International Seminar on ‘Creating & Teaching Music Patterns’

Page | 265

Figure 3 Figure 3.Sthai in Ada Chautal, Raga Yaman(Trivedi, रागपवबोध: लमश्रबानी 2012)

Because this composition starts at the 12th beat, most of the first row is empty and the composition takes two whole

rows. This demonstrates inefficient space use in Bhatkhande.

OmeSwarlipi has been designed with the requirements of the reader, the writer and the medium in

mind. The following section discusses aspects of the design.

Design

Glyph Design

The glyphs used for notation in OmeSwarlipi are derived from Devanagari and Roman scripts. The

symbols used for notes are simplified forms of their Devanagari counterparts, except for that of

Shadaj which is a circle to indicate its foundational stature (Trivedi, स्वरलिलिअन्कन:

साववभौलमकताअथवािूर्ावलभव्यलि 2008). The evolution of the glyphs is shown in Figure 4. In addition to

simplification, there is also some stylization to reduce the number of shapes, thus making it easier to

learn. For example, Gandhar and Pancham are mirror images of each other, as are Madhyam and

Nishad.

Figure 4 Evolution of OmeSwarlipi glyphs from Devanagari

Department of Instrumental Music, Rabindra Bharati University | 16-18 December, 2013

Proceedings

International Seminar on ‘Creating & Teaching Music Patterns’

The variant (Vikrit) forms of flat (Komal) notes are expressed with an underline. The variant form of

sharp (Teevra) Madhyam is expressed as a vertical bar above the note.

The symbols used for strokes (Mizrab Bol-s) are the Roman letters d, r, D, R and ∂r. Capitalization

expresses stress of stroke; thus d corresponds to da and D corresponds to Dā. The symbol for dir,∂r

uses the Mathematical differential sign instead of Roman d and is italicized in order to differentiate

Page | 266

from d r which corresponds to dara.

Modifier characters, such as those for upper or lower octaves, or for Gamak, or for Meend, are zerospaced characters. This means that they take no horizontal space themselves, instead project

outside on to the next (in case of Meend) or previous (for all the rest) character. They are meant to

be used in conjunction with a note character.

The font is monospaced, which means that each character takes exactly the same amount of space.

This allows the user to write vertically aligned compositions, which is necessary since a composition

must have three layers of information: the notes, the strokes, and the beats, all of which must be

synchronized when writing just as they are when playing.

Keyboard Design

The current version of OmeSwarlipi has 45 glyphs: 7 for notes in their natural form; 4 for flat notes

Rishabh, Gandhar, Dhaivat, and Nishad; 1 for sharp note Madhyam; 2 for marking upper or lower

octave of preceding note; 5 for strokes da, ra, Dā, Rā, and dir; 10 for the numerals 0 to 9; 2 for

separators; 2 for parentheses; 1 for the number sign #; 2 for beat marking Sam and Khali; 1 for

comma; 2 kinds of hyphens for representing different gaps; 4 for Meend marking the start,

continuation, end, and stroke; 1 for Gamak; and the last a compulsory Not Defined character. A full

listing and key-map can be found in Table 3.

The notes are assigned to their first letters. Variant of a note is accessed by using a modifier key in

addition to the normal one. Any further modifiers are added by using supplementary keys after the

original note. These too are assigned to the relevant first letter, such as u for Upper octave, l for

Lower octave, and v for Vibration (Gamak). Other sets of related characters, such as Mizrab Bol-s or

Meend characters, are grouped together according to their function. Note modifiers, which affect a

single note, are applied after the note. Phrase modifiers, which affect the entire phrase (such as

Meend characters), are applied before the note. All these design choices make for an intuitive

experience that is easy to learn and quick to master.

The seven notes have been mapped to the first letter of their names: Shadaj = s, Rishabh = r,

Gandhar = g, Madhyam = m, Pancham = p, Dhaivat = d, and Nishad = n. This helps learn the

keyboard and makes typing natural. Since Shift is a modifier key, it is a natural choice for expressing

a variant of a note. Flat and sharp variants of a note (the VikritSwara-s) can be typed by capitalizing

the relevant note. Thus, we have KomalRishabh = R, KomalGandhar = G, TeevraMadhyam = M,

KomalDhaivat = D, and KomalNishad = N. Octaves can be typed by the u and l keys, which add a dot

above or below the preceding character respectively. The v key will add a Gamak sign over the

preceding character.

Mizrab Bol-s, or stroke notation, is relegated to the upper right corner of the keyboard. The upper

keys of [and] represent the stronger strokes Dā and Rā, while the keys immediately below ; and ‘

represent the weaker strokes da and ra. The \ key, which is often larger in size than regular keys,

types the double-spaced dir character. Dir was made into its own character because of the

frequency of its use. In addition, the - key is also used in Mizrab Bol-s.

Department of Instrumental Music, Rabindra Bharati University | 16-18 December, 2013

Proceedings

International Seminar on ‘Creating & Teaching Music Patterns’

Page | 267

Figure 5 Glyphs and Key Mappings of OmeSwarlipi

Meend symbols, on the other hand, reside together in the upper left corner of the keyboard. In

order to achieve a typographic representation of arcs of an arbitrary length, the Meend symbol —

usually represented as an arc spanning the length of the phrase — is split into three components:

the beginning, the middle, and the end. The beginning is typed using q immediately before the first

note of the phrase. Then, each note in the phrase except for the last is preceded by w. Finally, the

Department of Instrumental Music, Rabindra Bharati University | 16-18 December, 2013

Proceedings

International Seminar on ‘Creating & Teaching Music Patterns’

last note is preceded by e to indicate the end of the Meend. In addition, the capital W key

represents a stroke in the Meend, to indicate that the note should be stroked during the Meend.

Omescribe

Page | 268

Figure 6 Screenshot of current beta of Omescribe, available at http://beta.omescribe.com

Department of Instrumental Music, Rabindra Bharati University | 16-18 December, 2013

Proceedings

International Seminar on ‘Creating & Teaching Music Patterns’

The font can be used in documents and presentations, in publishing (Trivedi, Sitar Compositions in

Ome Swarlipi 2011), and on the web at www.omescribe.com.

This plain-text representation, when combined with the monospaced quality, allows the use of a

number of modern computational facilities. Finding and replacing, for example, is readily doable

with any tool such as sed, Notepad, or Microsoft Word. Another example is version control: since

git, svn and other tools can track all changes to text documents, seeing the evolution of a Page | 269

composition, or keeping backups, or comparing versions, is easily done. A simple representation

such as this facilitates complex user behavior, such as real-time collaboration on a composition by a

number of participants.

Since the purpose of writing is to share with others, our current efforts are to develop a place on the

web that allows people to write, share, and interact with compositions in OmeSwarlipi. A beta is

available at http://beta.omescribe.com and more details can be found at www.omescribe.com. The

beta allows users to write compositions in OmeSwarlipi and save them by downloading as a PDF file.

Figure 6 is a screenshot of the current beta of Omescribe.

This fundamental proof of concept is to gauge the people’s demand for such a tool. If met with

enough demand, we will continue to add features to this tool: including ability to save and maintain

documents online, to share documents with others by sending them a URL to the composition,

embed compositions in web pages, comment on other’s compositions, a history view of a

composition’s evolution, and the ability to collaborate on compositions.

Results

OmeSwarlipi is perfect for modern times because it satisfies all three parties. It addresses the

requirements of the reader because it is easy to understand, since it uses simple characters that are

easy to learn, especially when one is familiar with their Devanagari roots. The style is consistent

since it includes all three aspects of music representation – notes, strokes and beats. It is

harmonious as all parts are written together and can be read in one flow.

It solves problems of the writers by being expressive, even more so than Bhatkhande since it has a

number of features such as Meend and Mizrab Bol-s built in to the script, which were later additions

to Bhatkhande. It is infinitely compose-able, and gives the writer flexibility like no other solution. It

is also efficient, since it takes less space than Bhatkhande, as well as self-contained, because it can

represent an entire composition in plain text without the need of a word processor. It is also easily

transferable, since the composition can be viewed on any platform that has the font installed, and

everywhere on the web with the support of webfonts.

It is a well-defined medium since it has an idiomatic style, and can be easily transferred by copypasting content from any application to another. It can be used in documents, presentations, emails,

in print and on the web. It can also be written down by hand, and then retyped into a computer. It is

a compact representation since a composition written in OmeSwarlipi takes less than a third of the

visual space required by a Bhatkhande composition. There is also minimal overhead, since apart

from specifying the font there is no other information that needs to be specified.

Department of Instrumental Music, Rabindra Bharati University | 16-18 December, 2013

Proceedings

International Seminar on ‘Creating & Teaching Music Patterns’

Page | 270

Figure 7 Sthai in Teen Tal, Raga Bilawal

Future Work

Our immediate goal is to bring OmeSwarlipi to the masses via Omescribe. While the current beta

allows users to write and save compositions in PDF files, we have received a number of requests for

an improved, more feature-rich application. The next version, currently in development, will allow

users to have any number of compositions in their account, to organize and manage them, and

share the compositions with other people.

In addition to the work on Omescribe, there is more work being done on the font itself. The next

version of OmeSwarlipi will support Ati-Tar and Ati-Mandra octaves, symbols for Ghaseet, a greater

variation of dashes, and more. Backwards compatibility will be a high priority so as to have minimal

effect on work done using prior versions of the font.

A frequent request, especially from vocalists and lyricists, is the ability to write words in Hindi (or

other languages) below the notes in OmeSwarlipi. This is difficult for Hindi, and most Indic

languages, because they are written using Abugida Scripts (Wikipedia 2013). Abugida Scripts use

vowels as modifier symbols that combine with consonants to make the final grapheme. Because of

the variety of combinations, it is difficult to make a monospaced version of an Abugida Script (such

as Hindi), and monospacing is a fundamental requirement for a font to follow OmeSwarlipi. We look

forward to work by other researchers in this field, for it will greatly complement our efforts.

A similar request for TablaBol-s is also made from time to time. Perhaps a technique similar to

Mizrab Bol-s can be adopted to represent them, however TablaBol-s are more numerous and may

require a more complex treatment. Our focus with OmeSwarlipi is on Mizrab Bol-s and string

instrumentation, since we stem from Misrabani style of playing instruments. However, we are

excited to present our ideas to the larger music community, and hope it will help others with more

specialized interests to develop compatible solutions.

Conclusion

OmeSwarlipi was developed after facing a number of problems with Bhatkhande script. It has been

through various trials over the last six years, and we continue to explore new avenues where it may

be of use. In this study we looked at the prominent technique for writing music in India, identified its

advantages and disadvantages, and described our solution to the limits of said technique. We

believe that OmeSwarlipimeets the nexus of usability and expressiveness to gain popular adoption

in the music community, and carry music notation into the twenty first century.

Department of Instrumental Music, Rabindra Bharati University | 16-18 December, 2013

Proceedings

International Seminar on ‘Creating & Teaching Music Patterns’

References

Quinion, M. "Vulgar Fractions." World Wide Words. March 3, 2007. http://www.worldwidewords.org/qa/qavul1.htm (accessed September 7, 2013).

Strizver,

I.

"Making

Fractions

in

OpenType."

Fonts.com.

March

10,

2006.

http://www.fonts.com/content/learning/fyti/using-type-tools/opentype-fractions (accessed September 7, 2013).

Trivedi, R. रागलवबोध: लमश्रबानी. Vol. 1. New Delhi: Delhi University, 2012.

Trivedi, R. "स्वरलिलिअन्कन: साववभौलमकताअथवािूर्ावलभव्यलि." In भारतीयशास्त्रीयसंगीत: शास्त्र, लशक्षर्वप्रयोग, edited

by R Trivedi, 77-95. Omenad, 2008.

—. Sitar Compositions in Ome Swarlipi. Omenad, 2011.

Widdess, R. "The Oral in Writing: Early Indian Musical Notations." Early Music 24, no. 3 (1996): 391-406.

Wikipedia. Abugida. August 29, 2013. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abugida (accessed October 29, 2013).

Department of Instrumental Music, Rabindra Bharati University | 16-18 December, 2013

Page | 271