Smith, Michael, Institutionalization, Policy Adaptation and European

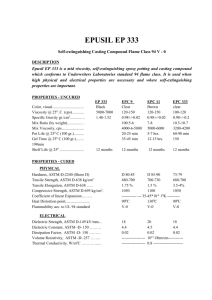

advertisement