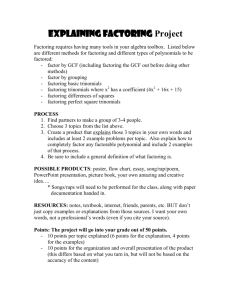

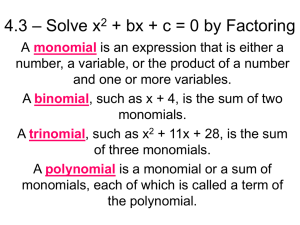

The Role of “Reverse Factoring”

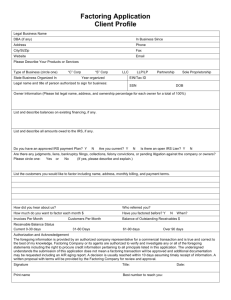

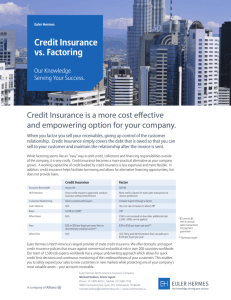

advertisement