total factor productivity growth in east asia: a critical survey

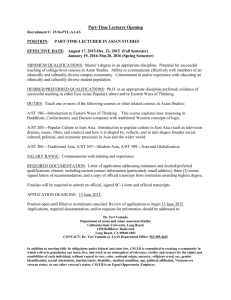

advertisement