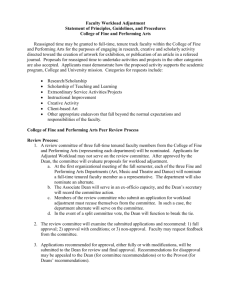

review of the GMS global sum formula

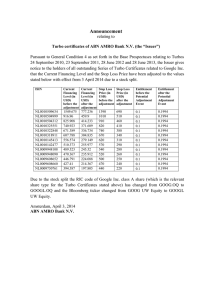

advertisement