Peirce Some Consequences of Four Incapacities

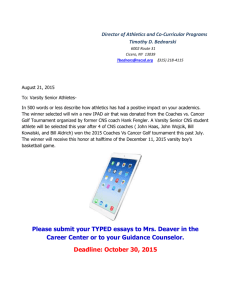

advertisement