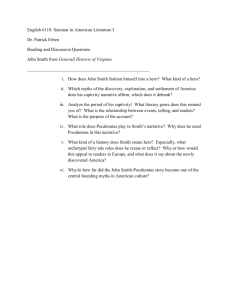

Employment Division v. Smith: The Supreme Court Alters the State

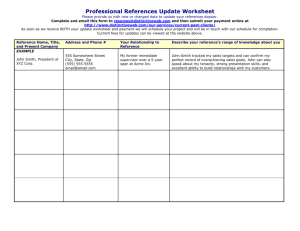

advertisement