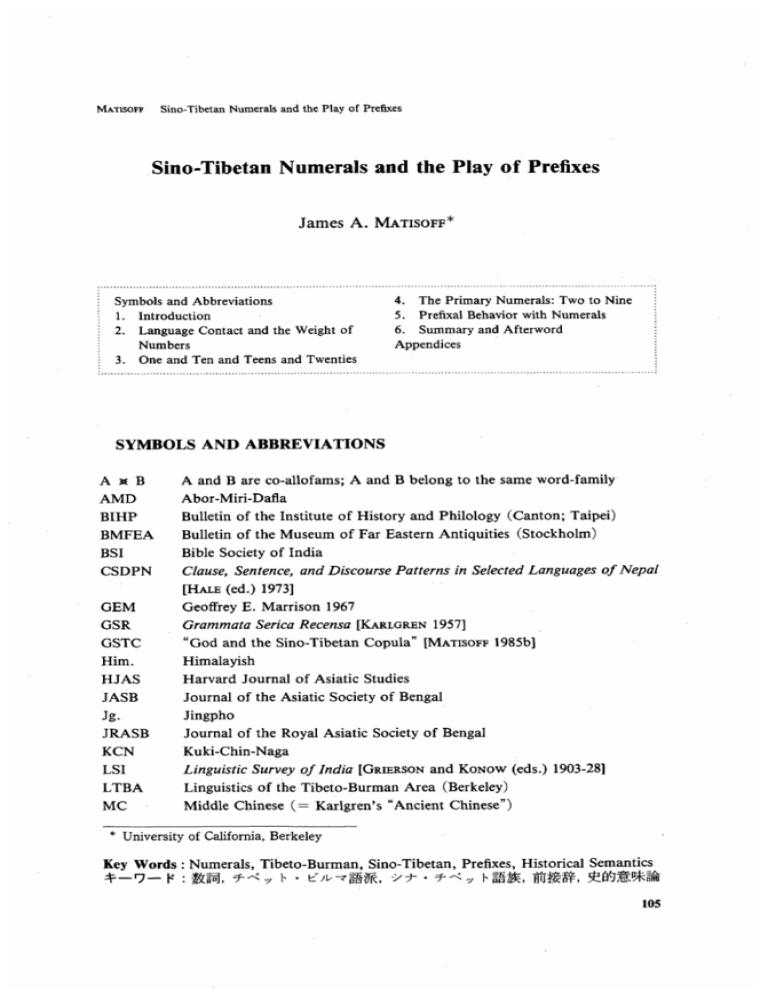

Sino-Tibetan Numerals: Prefixes & Language Contact

advertisement