At Face Value - Institute of Management Accountants

At Face Value

July 26, Helsinki, Finland

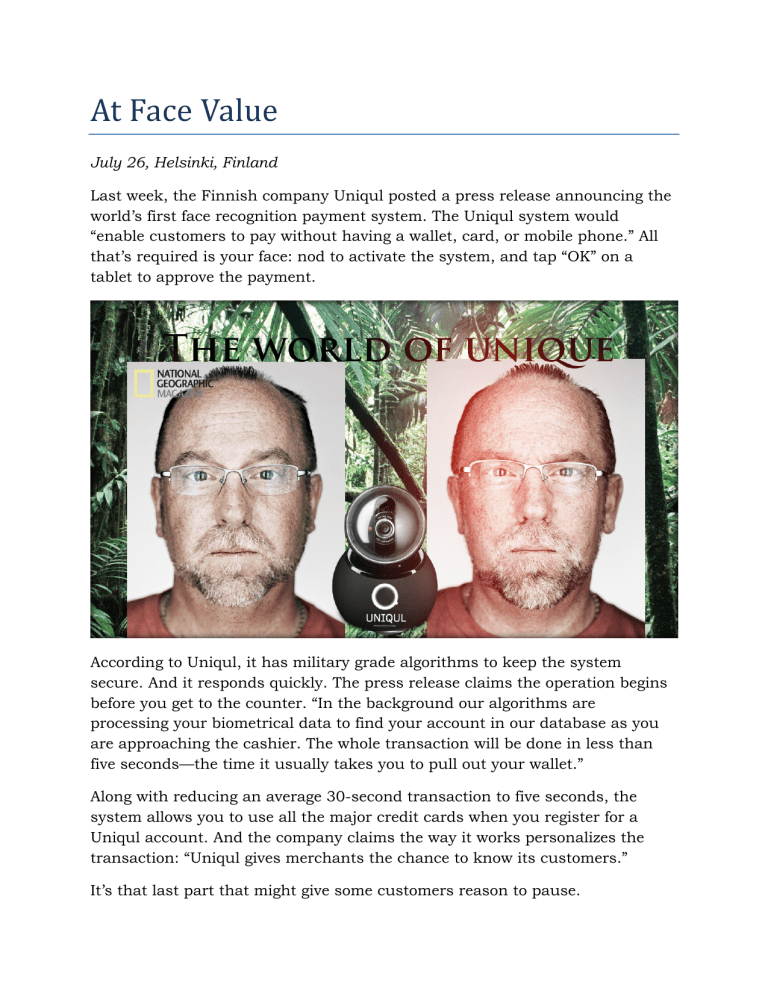

Last week, the Finnish company Uniqul posted a press release announcing the world’s first face recognition payment system. The Uniqul system would

“enable customers to pay without having a wallet, card, or mobile phone.” All that’s required is your face: nod to activate the system, and tap “OK” on a tablet to approve the payment.

According to Uniqul, it has military grade algorithms to keep the system secure. And it responds quickly. The press release claims the operation begins before you get to the counter. “In the background our algorithms are processing your biometrical data to find your account in our database as you are approaching the cashier. The whole transaction will be done in less than five seconds—the time it usually takes you to pull out your wallet.”

Along with reducing an average 30-second transaction to five seconds, the system allows you to use all the major credit cards when you register for a

Uniqul account. And the company claims the way it works personalizes the transaction: “Uniqul gives merchants the chance to know its customers.”

It’s that last part that might give some customers reason to pause.

The way the Uniqul system monetizes your face is very interesting. It’s based on locale, with the cheapest charges for the most local vendors. Here’s how it will work once it’s deployed in the Helsinki area:

“As for the pricing of our product we wanted to keep the customer in charge and that means that the individual users will be paying a monthly subscription fee as follows: As most people mainly visit shops near their work and home we decided to set the first fee level, 0.99€ [$1.31], to a 1-2 km radius from a user chosen point. Radius is dependent on the number of Uniqul terminals within the area. The next level, 1.99€ [$2.63], covers a specified city and is perfect for users who live and work within the same city, but want to use Uniqul in a wider area. The third level, 2.99€ [$3.95], covers a city and nearby suburbs, and is ideal for commuters who want the shopping convenience of Uniqul both when grocery shopping close to home and when buying lunch at work. The last level, 6.99€ [$9.23], is targeted towards frequent travellers who want total freedom from their wallet, and covers worldwide use of Uniqul.”

Diebold QR/Facial Recognition ATMs

The day after the Uniqul announcement, the British site Daily Mail Online posted a story by Victoria Woollaston about a next-generation cash machine from Diebold that will replace bank cards with facial recognition or QR codes.

At the current ATM conference in London, Diebold is showcasing a portable touch-screen ATM that’s Wi-Fi enabled and two-thirds the size of a conventional cash machine.

The Millennial ATM, from the Ohio-based security firm Diebold, uses a touchscreen that functions like a tablet. Authentication of the customer relies on facial recognition or QR codes. (The image below is a working Quick

Response code for the Wikipedia URL.)

If the ATM is QR-enabled, you scan an onscreen QR code, which establishes a connection between your mobile device and the ATM. In the Cloud, the ATM verifies your identity, and a transaction screen appears on your device. You tap in amounts, and a unique, one-time code is sent to your phone. Sending that code back completes the transaction. The system is being developed to also use facial recognition instead of the QR codes to verify the customer.

Diebold has announced it hopes to have the Millennium ready for distribution in 18 months.

History of Face Recognition

The basic technology for facial recognition by computers is about 50 years old.

Pioneers Woody Bledsoe, Helen Chan Wolf, and Charles Bisson began their work in 1965, and the progress has been slow despite government support.

Early two-dimensional systems might use an algorithm that tried to match distinguishing features with a database or a statistical procedure that reduces a set of measurements to values that are compared to templates. Either system has built-in difficulties with the angle of the face and the lighting.

More recent three-dimensional recognition systems use 3D sensors to map the shape of the face, particularly the distinctive features on the surface of face.

This system is more flexible about the angle of the view and more forgiving about lighting issues. The better 3D systems project multiple sources of light onto the face that eliminate attempts to defeat it with photographs or makeup.

But what about the problem of the identical twin? An additional level of analysis called skin texture analysis scans for more detail and differences, which, according to Mark Williams, can increase accuracy by 25% and separate the twins.

As a technology, facial recognition is a lot like voice recognition. Both have had long and slow developmental curves. Both require intensive processing power and have had to wait for hardware to evolve along with them. And finally, both try to emulate what we think of as particularly human skills— pattern recognition and speech. And for that reason, there’s a built-in resistance to adoption that other technologies haven’t had to deal with.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology neuroscientist Tomaso Poggio has an interesting theory about the difficulty of learning to recognize a face. For humans, he says, the skill is a legacy, not a learned ability. He writes,

“Recognizing objects in difficult situations means generalizing. A newborn baby

can recognize the basic pattern of a face. It has been learned by evolution, not by the individual.”

This ability to sort out patterns is a skill that, for humans, has become the most essential survival skill. It’s been wired in, and hence, we’re still here, building our cities and scoping out the designs of chemicals that thwart diseases. The fact that certain damage to the wiring can cause prosopagnosia, an inability to recognize faces, seems to bear out the claim that recognition is inherited.

So, if the computer began with prosopagnosia as part of its natural state, it’s no wonder we’re now 50 years into our attempt to teach it what babies already know.

Michael Castelluccio