Prognostic Predicament: Don`t Take the Audiogram at Face Value

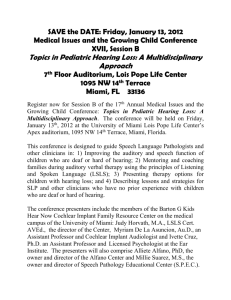

advertisement

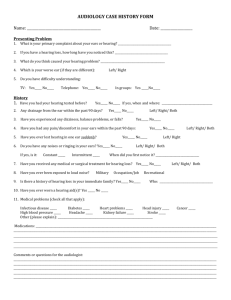

CSI: AUDIOLOGY WELCOME BACK to an ongoing series that challenges the audiologist to identify a diagnosis for a case study based on a listing and explanation of the nonaudiology and audiology test battery. It is important to recognize that a hearing loss or a vestibular issue may be a manifestation of a systemic illness. Being part of the diagnostic and treatment “team” is a crucial role of the audiologist. Securing the definitive diagnosis is rewarding for the audiologist and enhances patient hearing and balance health care and, often, quality of life. —Hillary Snapp, Investigator-in-Chief CSI Reference Guide: Visit www.audiology.org and search keywords “CSI Reference Guide.” 54 AUDIOLOGY TODAY Mar/Apr 2015 Prognostic Predicament: Don’t Take the Audiogram at Face Value By Sarah Sydlowski Case History A 45-year-old male was referred for a cochlear implant (CI) evaluation. Audiologic history included the following: 15-year history of progressive bilateral hearing loss Perceived his right ear to be worse than his left ear Bilateral, ringing tinnitus that was a 6/10 on a Tinnitus Distress Scale 13-year use of bilateral behindthe-ear hearing aids that were approximately three years old Poor word recognition ability, even in aided condition Poor speech perception in noisy environments and group settings Reliance on visual cues for communication purposes Occasional imbalance, but no true vertigo Denied family history of hearing loss, significant noise exposure, middle-ear disorder, aural pressure or fullness, or other otologic complaints. Audiometric Findings Otoscopic examination revealed clear ear canals and intact tympanic membranes bilaterally. Audiometric evaluation (FIGURE 1) revealed moderate sensorineural hearing loss through 500 Hz dropping to profound at 1000 Hz and above. Word recognition was 0 percent at 25 dB SL in the right ear and 10 percent in the left ear (patient could not tolerate higher presentation levels). Tympanometry indicated normal middle ear pressure, mobility, and volume bilaterally. Acoustic reflexes were absent in the ipsilateral and contralateral conditions for all frequencies tested. Review of previous audiograms over 10 years revealed bilateral, asymmetric (right worse than left), sloping, progressive sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) with gradual decline in word recognition. Vol 27 No 2 CSI: AUDIOLOGY The patient’s hearing aids were evaluated using real ear measures and were found to meet prescribed targets as closely as possible, given the degree of hearing loss. Aided testing was then completed in a sound booth with speech materials presented at 60 dBA from 0° azimuth. Results are summarized in TABLE 1. Does the patient report and audiometric findings assist you in making a differential diagnosis? Does the etiology of the patient’s hearing loss matter when considering cochlear implant candidacy? Consider the Facts Progressive bilateral, asymmetric sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, and imbalance (no true vertigo) Audiometric results more severe than hearing loss that could be attributed to his limited history of noise exposure or aging No family history of hearing loss that would suggest a genetic component Very poor word recognition despite history of consistent hearing aid use Limited demonstrated benefit from hearing aids on aided speech-perception measures The patient meets FDA criteria for cochlear implantation and his audiometric evaluation seems relatively unremarkable, although some asymmetry was noted, and we do not know the etiology of the hearing loss. Should we proceed with cochlear implantation? Is there other information that might be relevant? Other Medical History Upon further questioning, the patient revealed that he had sustained a head injury in a motor vehicle at four years of age. He did not lose consciousness, but the report suggests it was a significant injury. He reported a history of headaches beginning at age eight that were noted to occur three to four times per year. Around age 22, he began having more severe headaches along with tingling in his TABLE 1. Preoperative Aided Speech-Recognition Results in the Sound Booth with Speech Materials Presented at 60 dBA from 0° Azimuth Right Aided Left Aided Bilaterally Aided CNC Words 20% words; 48% phonemes 20% words; 58% phonemes 38% words; 66% phonemes AzBio Sentences, Quiet 21% 42% 59% AzBio Sentences, +10 SNR 0% 12% 18% Note: CNC = consonant-nucleus-consonant; SNR = signal-to-noise ratio. FIGURE 1. Results from audiometric evaluation revealing bilateral moderate sensorineural hearing loss through 500 Hz dropping to asymmetric profound hearing loss from 1000 to 8000 Hz. Vol 27 No 2 Mar/Apr 2015 AUDIOLOGY TODAY 55 CSI: AUDIOLOGY extremities. He also developed gait and coordination problems with a tendency to stumble. He began to notice bilateral hearing loss and tinnitus in his late twenties, which has steadily progressed. Most recently, he has noticed urinary incontinence. Subsequent to the presentation of these neurologic symptoms, he had several spinal taps, which revealed blood products in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and consistently elevated pressure. The patient’s medical history is somewhat unusual and should trigger the clinician to suggest further medical evaluation to determine the possibility of an associated etiology. Medical evaluation led to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with results consistent with superficial siderosis of the central nervous system (SSCN). Does this diagnosis influence the patient’s candidacy for cochlear implantation? Diagnosis SSCN is an extremely rare neurotologic disorder involving chronic hemorrhaging into the subarachnoid space and subsequent deposition of hemosiderin (an iron-protein) onto susceptible neural structures including the brainstem, cerebellum, and CNVIII (Tomlinson and Walton, 1964; Parnes and Weaver, 1992; Kale et al, 2003; Vibert el al, 2004). This hemorrhaging typically occurs due to the presence of dural tears around the brain or spinal cord (Parnes and Weaver, 1992; Cohen-Gadol et al, 2006) resulting from vascular malformations, tumor growth or resection, or trauma (Tomlinson and Walton, 1964; Dhooge et al, 2002). As red blood cells circulate within the cerebrospinal fluid and degenerate (Takasaki et al, 2000; Dhooge et al, 56 AUDIOLOGY TODAY Mar/Apr 2015 2002), hemosiderin is produced. Glial iron clearance mechanisms cannot keep up with the iron influx, and exposed structures essentially rust, causing cell death and neuronal vulnerability. In the current case, the nonspecific findings of bilateral, progressive sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, and imbalance alone are inadequate to pinpoint an etiology. However, the presence of SNHL exceeding hearing loss that could be attributed to aging, observation of ataxia, history of head trauma, and eventually confirmation of hemosiderin staining on MRI, all point to classic presentation of superficial siderosis of the central nervous system (SSCN). The cardinal feature of SSCN is hearing loss (95 percent) (Fearnley et al, 1995); however, a variety of neurological signs and symptoms may be present to varying degrees, including but not limited to gait ataxia, widebased gait, dizziness/imbalance, dementia, anosmia, neurogenic bladder (including incontinence, voiding difficulty, or urgency), bowel incontinence, aniscoria, dysarthria, spasticity, tinnitus, diplopia, headaches, seizures, hydrocephalus, hypogeusia, memory loss, cognitive decline, seizures, extra-ocular motor palsies, neck pain, back pain, nystagmus, and dysphagia (Parnes and Weaver, 1992; Fearnley et al, 1995; Kale et al, 2003). Hearing loss resulting from SSCN is probably retrocochlear in nature (Yamana et al, 2001; Ushio et al, 2006) due to the largely glial myelination of CNVIII and the diffuse exposure of the cochlear nucleus to CSF circulating through the fourth ventricle. However, several studies have demonstrated that peripheral auditory structures may also be impacted, although how they become affected is unclear (Irving and Graham, 1996; Takasaki et al, 2000; Yamana et al, 2001; Weekamp et al, 2003; Vibert et al, 2004; Hathaway et al, 2006; Kim et al, 2006; Sydlowski et al, 2013). Possible mechanisms include interruption of cochlear vasculature due to thickening of CNVIII (Yamana et al, 2001), hair cell degeneration secondary to deafferentation of CNVIII (Prasher et al, 1995), or circulation of hemosiderin within the cochlea via a patent cochlear aqueduct (Wlodyka, 1978) or internal auditory canal (Holden and Schuknecht, 1968). Regardless of site(s) of lesion, hearing loss is usually bilateral, asymmetric, progressive, sloping SNHL (Sydlowski et al, 2013). Word recognition varies but tends to be disproportionately poor (Sydlowski et al, 2011) and progressively worsens. There has been some speculation that individuals with intra-axial brainstem lesions or lesions at the level of the cerebellopontine angle may have better speech recognition ability than those with extra-axially located lesions (Mobley et al, 2002), but further research is necessary. SSCN is difficult to diagnose because of variable and nonspecific symptoms that often present decades after initial onset of the disorder (Fearnley et al, 1995; Offenbacher et al, 1996). Although otologic symptoms such as hearing loss, tinnitus, and imbalance are frequently among the first and most commonly reported symptoms (Sydlowski et al, 2013), many patients exhibit a very long asymptomatic phase (months to many years) after bleeding begins. This prolonged separation of onset of disorder and development of symptoms coupled with fairly “typical” sloping SNHL makes suspicion of SSCN based solely on audiometric battery unlikely. SSCN is ultimately identified by hypointensity surrounding affected structures on gradient echo T2-weighted (T2*) MRI images (Parnes and Weaver, 1992; Vol 27 No 2 CSI: AUDIOLOGY Padberg and Hoogenraad, 2000; Ushio et al, 2006). Discussion Awareness of this esoteric disorder is important for audiologists for several reasons. First, SSCN is a perfect example of the importance of integrating audiologic and medical histories. In this case, the patient’s reported history of head trauma and constellation of neurological complaints, coupled with worsethan-expected hearing loss without another identifiable etiology, should prompt recommendation for medical (ideally neurologic) evaluation if the diagnosis of SSCN has not already been made, even though the hearing loss was essentially unremarkable except for high frequency asymmetry. Second, a diagnosis of SSCN introduces a very different prognosis for patients than more common presbycusis, although pure tone thresholds may look similar. Because the presence of hemosiderin in the subarachnoid space results in progressive destruction, locating and ablating the source of the hemorrhage is a priority. Methods described in the literature have included surgical ablation of the bleeding source and iron chelation therapy (Miliaras et al, 2005). Avoidance of anticoagulant and antiplatelet medications, including aspirin, has been suggested to slow bleeding into the subarachnoid space (Dodson et al, 2004). However, the source of bleeding is usually microscopic and is only found in 50 percent of cases. Even if bleeding ceases, once neural structures are encrusted with hemosiderin, symptoms may continue to progress (Cohen-Gadol et al, 2006). Because of its retrocochlear component and likelihood of progression, clinicians should recognize that the potential for improved speech recognition with hearing aid and/ Vol 27 No 2 or cochlear implant use may be limited or may deteriorate over time (Sydlowski et al, 2009). While SSCN is not a contraindication to cochlear implantation, research suggests outcomes may be variable (Sydlowski et al, 2009) and appropriate counseling regarding expectations is critical. Finally, even in cases where most components of the standard audiologic battery may not appear retrocochlear in nature, inclusion of objective measures such as acoustic reflexes and otoacoustic emissions are important for diagnostic as well as for hearing aid fitting purposes. In cases of predominantly retrocochlear disorders such as SSCN or auditory neuropathy spectrum disorder (ANSD), special care must be taken with hearing aid fitting to avoid overamplification and damage to cochlear structures. Given the diagnosis of superficial siderosis, is there any additional audiologic testing that may be warranted? Objective Findings Objective measures may be valuable for evaluating the lesion site (particularly confirming possible cochlear involvement), although there has been no evidence to suggest that inclusion of objective measures in SSCN can predict potential outcomes following cochlear implantation. In the current case, electrocochleography (ECochG), auditory brainstem response (ABR), and distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs) evaluated for the frequencies of 2000 through 8000 Hz all resulted in absent responses bilaterally, consistent with the degree of hearing loss and likely cochlear involvement, although whether or not the peripheral dysfunction is due to SSCN or other causes cannot be determined. Despite confirmed peripheral abnormality, the diagnosis of SSCN also makes retrocochlear involvement highly probable, so care was taken when counseling the patient regarding prognosis for speech recognition following cochlear implantation. Key Points Comprehensive case history, including determination of etiology when possible, is essential, particularly when considering surgical intervention options such as cochlear implantation. Hearing loss, even symmetrical hearing loss that cannot be explained by aging or other factors, should trigger clinicians to consider medical evaluation. The audiogram in isolation will frequently not tell the whole story. Etiology and site of lesion can alter prognosis and should be thoroughly investigated and incorporated into counseling. Final Thoughts If asked whether they are familiar with disorders that result in hearing loss in 95 percent of patients, most audiologists would not hesitate to respond in the affirmative. However, SSCN is not well known to audiologists because of its exceptionally rare presentation. Reviewing cases involving complex disorders, such as SSCN, highlights the importance of approaching audiologic evaluation with a broad viewpoint and reminds audiologists of the importance of gathering comprehensive diagnostic information in order to accurately identify hearing loss, develop a reasonable prognosis, and provide appropriate management recommendations in special populations. Mar/Apr 2015 AUDIOLOGY TODAY 57 CSI: AUDIOLOGY Sarah Sydlowski, AuD, PhD, is audiology director of the Hearing Implant Program at the Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio. References Cohen-Gadol AA, Jacob JT, Wright RA, Ahlskog JE. (2006) Superficial siderosis of the central nervous system. In: Neurological Therapeutics Principles and Practice. Abingdon: Informa Healthcare, 742–746. Dhooge IJM, De Vel E, Urgell H, et al. (2002) Cochlear implantation in a patient with superficial siderosis of the central nervous system. Otol Neurotol 23:468–472. Dodson KM, Sismanis A, Nance WE. (2004) Superficial siderosis: a potentially important cause of genetic as well as non-genetic deafness. Am J Med Genet 130:22–25. Fearnley JM, Stevens JM, Rudge P. (1995) Superficial siderosis of the central nervous system. Brain 118:1051–1066. Hathaway B, Hirsch B, Branstetter B. (2006) Successful cochlear implantation in a patient with superficial siderosis. Am J Otolaryngol 27:255–258. Holden HB, Schuknecht HF. (1968) Distribution pattern of blood in the inner ear following spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Laryngol Otol 82:321–329. Irving RM, Graham JM. (1996) Cochlear implantation in superficial siderosis. J Laryngol Otol 110:1151–1153. Kale SU, Donaldson I, West RJ, et al. (2003) Superficial siderosis of the meninges and its otolaryngologic connection: a series of five patients. Otol Neurotol 24:90–95. 58 AUDIOLOGY TODAY Mar/Apr 2015 Kim CS, Song JJ, Park MH, et al. (2006) Cochlear implantation in superficial siderosis. Acta Otolaryngol 126:892–896. Miliaras G, Bostantjopoulou S, Argyropoulou M, et al. (2005) Superficial siderosis of the CNS: report of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 108:499–502. Mobley SR, Odabasi O, Ahsan S, et al. (2002) Distortion-product otoacoustic emissions in nonacoustic tumors of the cerebellopontine angle. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 126:115–120. Offenbacher H, Fazekas F, Schmidt R, et al. (1996) Superficial siderosis of the central nervous system: MRI findings and clinical significance. Neuroradiology 38:S51–S56. Padberg M, Hoogenraad TU. (2000) Cerebral siderosis: deafness by a spinal tumor. J Neurol 247:473. Parnes SM, Weaver SA. (1992) Superficial siderosis of the central nervous system: a neglected cause of sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 107:69–77. Prasher DK, Tun T, Brookes GB, et al. (1995) Mechanism of hearing loss in acoustic neuroma: an otoacoustic emission study. Acta Otolaryngol 115:375–381. Sydlowski SA, Cevette MJ, Shallop J, et al. (2009) Cochlear implant patients with superficial siderosis. J Am Acad Audiol 20:348–352. Sydlowski SA, Levy M, Hanks WD, et al. (2013) Auditory profile in superficial siderosis of the central nervous system: a prospective study. Otol Neurotol 34:611–619. Takasaki K, Tanaka F, Shigeno K, et al. (2000) Superficial siderosis of the central nervous system: a case report on examination by ECoG and DPOAE. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 62:270–273. Tomlinson BE, Walton JN. (1964) Superficial haemosiderosis of the central nervous system. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 27:332–339. Ushio M, Iwasaki S, Sugasawa K, et al. (2006) Superficial siderosis causing retrolabyrinthine involvement in both cochlear and vestibular branches of the eighth cranial nerve. Acta Otolaryngol 126:997–1000. Vibert D, Häusler R, Lövblad O, et al. (2004) Hearing loss and vertigo in superficial siderosis of the central nervous system. Am J Otolaryngol 25:142–149. Weekamp HH, Huygen PLM, Merx JL, et al. (2003) Longitudinal analysis of hearing loss in a case of hemosiderosis of the central nervous system. Otol Neurotol 24:738–742. Wlodyka J. (1978) Studies on cochlear aqueduct patency. Ann Otol 87:22–28. Yamana T, Suzuki M, Kitano H. (2001) Neuro-otologic findings in a case of superficial siderosis with bilateral hearing impairment. J Otolaryngol 30:187–189. Sydlowski SA, Cevette MJ, Shallop J. (2011) Superficial siderosis of the central nervous system: phenotype and implications for audiology and otology. Otol Neurotol 32:902–908. Vol 27 No 2