Last chance to see… - University of the Western Cape

advertisement

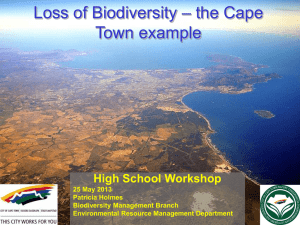

Last chance to see… the world that our Ancestors saw What would you do if… you read that a big multi-national company was to clear-fell some 10% of South Africa’s Afromontane forest due to the rarity value the timber fetches on the global markets, or that China has decided that it wants to cull 10% of the remaining panda population to provide a culinary delicacy for an elite few or that Australia has decided that it can harvest 10% of its great barrier reef to supply its burgeoning tourist market with cheap coral mementos. These scenarios are obviously outrageous, forests, pandas and coral reefs are conservation icons. However, there are many species and now entire ecosystems that are literally on the brink of extinction. Recently, while watching David Attenborough’s series “State of the Planet”, I was alarmed that to illustrate habitat loss linked to species extinction he used Lowland Fynbos around Cape Town. On reflection, is there a global biodiversity hot spot so rich and yet so perilously close to extinction? In becoming high priests of profit modern society is causing entire ecosystems to be knocking on the proverbial pearly gates? What are the conservation planners doing and is it a case of too little too late? The Ten Percent Capital Rule The IUCN (World Conservation Union) recommendations for conservation management, is to set aside at least 10% of each respective ecosystems within a national protected areas network. This 10% was to be applied by each nation, including South Africa, who was a signatory to the Convention on Biodiversity. Why is 10% considered to be the magical number? This seems to relate to hypothetical calculations derived from colonization and extinction of islands, where 90% of the species can still be maintained on 10% area. Some ecologists have argued that ecosystem integrity becomes compromised with a 60% loss of area. This 10% numeric has become fixed in policy frameworks world-wide. However, some species are able to avoid extinction even though their numbers remain low, whereas other species become extinct rather easily, and further it appears that rare species resist extinction with smaller population sizes than common species. The demise of the Passenger Pigeon is the best illustration, which went from being the most numerous bird species to extinct within two decades, simply because it had become “fun” to shoot. Many of these theoretical considerations are based on evenness in the distribution of species or vegetation types in a landscape, but we have common and rare species and vegetation types that are differently distributed (often clumped or naturally fragmented. A species or vegetation type that is naturally rare or highly clumped is usually able to survive with lower representation than a widespread and common species which has experienced a considerable loss by area. Often naturally fragmented and uneven distribution of species and vegetation types is the result of disturbances, both natural and human-induced. Although the term disturbance may sound bad, like fire (often reported as “destroying” fynbos) it actually provides opportunities to rejuvenate a species or a vegetation type. Fynbos is quite literally a phoenix and without fire it becomes senescent and its species richness declines. Grasslands, if they are not grazed by animals or periodically burnt may also become dominated by a competitive few with a loss of rarer species. Consequently many species occurrence and ecosystem forms have literally been molded by past events, which are infrequent to random in their occurrence. Such uncertainties within systems of chaos makes natural habitat management difficult, especially as animals move and plants simply hide their presence by way of seed banks in the soil. Failure to recognize that species are cryptic in their occurrence within an ecosystem has made it very difficult for ecologists to accurately state which species do and do not exist within a natural habitat. This is illustrated by the rare species of Priestleya which appeared after some 50 years of absence when a pine plantation on Table Mountain was cleared or the re-discovery of Channel-leaf Featherbush - Aulax cancellata once also locally common on this mountain. Species occurrence within a vegetation type or an ecosystem is influenced by the presence of other species and a variety of interactions such as competition between plant species and between animal species, through to facilitation where plants may use other plants, like a vine using a tree to reach for the sun. Plants and animals also interact with each other and animals aid sedentary plants with pollination and seed-dispersal services. Nevertheless as more natural habitat yields to insatiable human pressures for development, species are becoming increasingly isolated and restricted to their small islands of natural habitat, their relationship with each of their associates becoming compromised with inevitable species loss and ensuing extinction. Death Match: West Coast Renosterveld versus Sandplain Fynbos West Coast Renosterveld, Sandplain Fynbos and Coastal Thicket all make up the vegetation of the Cape Lowlands. The Coastal Thicket is largely derived from the Subtropical East Coast and occurs on dune sands which are alkaline in character. Both the Renosterveld and Sandplain Fynbos are floristically species rich and most of this floral richness occurs nowhere else (termed endemism). Sandplain fynbos occurs on the nutrient poor and older more leached sands that are acidic in nature. Like its cousin the Mountain Fynbos it has proteas, heaths (including ericas) and Cape reeds (Restio) as the dominant species. It is a vegetation type that requires burning periodically (12-15 years) but also has a conspicuous annual and geophyte presence. It is likely that low nutrients have prevented groups like the grasses from being more dominant, however, if Sandplain Fynbos becomes disturbed, invasive alien grasses are quick to encroach and difficult to eradicate. Rainfall in Sandplain Fynbos is generally much lower than in Mountain Fynbos and usually below 700mm per annum. West Coast Renosterveld occurs on the more nutrient rich and heavier shales with high clay content, so little of it is left that there is debate as to exactly what its ecological nature was? It is generally considered to be a shrubland-grassland mixture. Historical accounts of early travelers indicate that most of the big game such as Lion, Buffalo, Hyena and Eland occurred in these habitats. The role of fire in Renosterveld has been debated but essentially with animal grazing would have been important in maintaining and shaping plant communities. The fertile soils which supported West Coast Renosterveld have largely been transformed by agriculture, most notable wheat in the past and vineyards today. Sand Plain Fynbos and the West Coast Renosterveld are estimated to be about 70% and 90% transformed, leaving rather little left to start the process of conserving it. Unfortunately, these statistics, rather than being hard facts vary with interpretations and methods of determination. Firstly, the original distribution of these two vegetation types prior to human disturbance can only be deduced from early traveler’s journals together with inferring climate and soil characters. Even the term West Coast Renosterveld is ambiguous but expert consensus agrees that precious little of the lowlands are left, especially close to the City of Cape Town, and this may not be representative of what previously existed. Modern earth observing satellite images are useful for showing land use trends, but to translate these images into meaningful maps is difficult. Some transformed land uses such as wheat fields are easily mapped but encroachment of suburbia or the invasion of natural vegetation by woody alien species is problematic especially since accessible low-cost imagery is low resolution (only highway-size features are discernable). If we focus on a smaller area where detailed and geo-corrected photography is available like Greater Cape Town we can get very accurate estimates of what is remaining and it is possible to visit and assess these sites so the condition can also be determined. On these lowlands there are about 1500 species, 76 of which are endemic and 131 rare and endangered species. Here we have only 1% of the Cape Flats Sandplain Fynbos and 3% West Coast Renosterveld conserved, and for neither of these vegetation types can you achieve the desired conservation targets. Consequently all sites with these vegetation types are referred to as irreplaceable and form the basis for defining a vegetation type that is critically endangered and under the new EIA regulations of National Environmental Management Act (NEMA). Under this act any removal of a critically endangered vegetation type will require an environmental impact assessment. Using our death match analogy the Cape Flats Sand Plain Fynbos is most likely to be the first loser, due to its low formal conservation. Further, precious little is left and it is easily disturbed through nutrient enrichment. There is concern that even car exhaust emissions of nitrous oxide could increase soil nitrogen levels through precipitation, essentially acid rain. In contrast, Renosterveld occurs on nutrient rich substrates so should be less sensitive to nutrient loadings from human resources, and recent research suggests that fire has less of a role for maintaining its species richness but browsing and grazing by animals is important. Climate Change and especially elevated CO2 is considered to be another atmospheric fertilizer that will promote weedy species and consequently it could be expected to have more of an impact on the nutrient-poor Sandplain Fynbos. Other studies have suggested that in Renosterveld, small patch sizes do lead to a breakdown in services like pollination. Sandplain Fynbos will undoubtedly be similar. Conservation Planning: A Pandora’s Box of Algorithms Despite a lack of precision knowledge of what occurs where and in what condition, sophisticated numerical techniques have been developed which use species and vegetation types to maximize the biodiversity capital (even if it is only 10%) so as to be used for maximum benefit. These “optimized” solutions identify which remaining sites conserve the most representatives of species or vegetation types. There are a plethora of algorithms to calculate these solutions which most often use the rarest site or rarest vegetation type to start the prioritization. A few algorithms even use the proximity of similar natural habitat so as to configure solution that minimizes the distance plants and animals have to move from one remnant to another. Yet others take into account the geometry of the remnant patches and determine that circular areas will be better than elongated shapes, and this is based on minimizing edge effects, which usually experience higher disturbances. Without adding layers of information on human use for integration such as the use of biodiversity planning corridors this approach will only permit write-off of natural sites to provide the most amount of land for development. Unfortunately our two lowland vegetation types Sandplain Fynbos and West Coast Renosterveld present another problem for their systematic conservation: they pack almost the most number of species into the smallest footprint anywhere in the world, and their species composition changes across the landscape at rates unmatched. This means that the same type of vegetation can have very different species composition within a comparatively short distance. The implication of this is that you now need to ensure that even those isolated patches far from their neighbours should be included within the protected areas network, since they are more likely to contain a unique suit of species A Price on its Head Increasingly conservationists are being drawn into the realm of economics and to place value on natural assets, be it utility or aesthetic. This approach is leading to the trade and bartering of natural remnants. So proposed development in a sensitive environment will require that another similar area (similar species composition or vegetation type) in some way is secured through financing and is termed a biodiversity offset. While merit exists in this, at what point does the commodity become so rare that you are forbidden to trade in it like rhinoceros horns? Hopefully laws of demand and supply will inflate this valuation of natural habitats for biodiversity offsets as they become rarer to a situation where they cannot be traded when they get too rare. The biodiversity offset concept does not recognize that vegetation types like West Coast Renosterveld and Sandplain Fynbos remnants are virtually unique unless right next to one another. Will our valuations prove to have been realistic or will biodiversity have got shortchanged? Private ownership of land is a western concept alien to most of our ancestors, and indigenous cultures expressly acknowledge that humans are meant to be stewards of it and the plants and animals that are found on the land and in the water. While the General Electric Corporation opened the doors to patenting altered genes and therefore life itself, corporations like Monsanto have exploited that niche by securing literally thousands of patents under the pretext that because they mapped the DNA they own that life form, irrespective of whether they modified it or not, or if it were a cultivar that has been nurtured by generations of indigenous people. So it seems that biodiversity can also be owned and even stolen, does ownership mean you can dispose of it at will? If you were to own the Mona Lisa would society allow you to willingly destroy it? Having established that evergreen forests, pandas, Mona Lisa and biodiversity are owned, what is the responsibility attached to its ownership? A Botanical Society’s report some ten years ago listed Milnerton Race Course as the highest priority conservation site on the Cape Flats, yet it was sold for development that will conserve two isolated patches of Sandplain Fynbos. Kenilworth Race Course looks to have yet more development unless measures are taken and funds secured to safeguard it. Some 50ha of Driftsands Nature Reserve has been de-proclaimed to provide for development. The natural habitat on my own campus was rated 8th most important, and yet we have already seen a small part of its Sandplain Fynbos removed for a new building. Sites like Century City exist today with only a fringe of Sandplain Fynbos around the wetlands and Eskom brushcut yet another Sandplain Fynbos site. It seems a chain reaction of events is unfolding similar to a century ago that lead to the extinction of the Passenger Pigeon. Then a few greedy and hedonistic people insisted that it was their personal freedom and pleasure to shoot the last few birds (“last chance to shoot” hunting parties were organized to this end). Will our excuse also be a mixture of profit and pleasure? Biodiversity Stewardship Landowners who wish to develop on the last remnants of Sandplain Fynbos or Westcoast Renosterveld should realized their action are no different to eating panda paws from a dinning room table crafted from rare Afromontane timber. They are also depriving future generations of an experience. Further, by conserving such sites, we have some idea of what existed before the European colonists and global economies transformed them. The new EIA legislation needs to be applied to ensure that our crown jewels are conserved not just selective rare species that are the constituent mineral stones within the crown. With the new legislation and South Africa’s commitment to mapping all of the natural vegetation (currently there are a large number of fine-scale mapping projects) more rigorous and defensible planning procedures will ensure that we move away from piece-meal conservation efforts inherited from past legislation like the USA has with its Endangered Species Act. This act ultimately compromised biodiversity since it often lead to endangered species being identified and destroyed prior to the environmental impact assessment, a circumstance not unknown in South Africa. Unfortunately most developers still hold onto the view that the presence of a few rare or threatened species is of critical importance to conservation practice. This paradigm has been overturned so the habitats that support the species are the new currency for conservation. Nevertheless the divide between protected areas and development needs to be the basis for synergy. Currently Protected Areas are an offset to a landscape-wide trashing of the environment that will ultimately lead to both losses of natural habitat and increasingly unsustainable urban life styles. I do not believe that every remnant of vegetation needs to be fenced with restricted access, while there may be merit in particular cases, natural vegetation remnants could easily provide aesthetic but low maintenance landscaping , with value being added if used for monitoring of the urban environment and for education. Remnants of natural vegetation are part of our indigenous precolonial heritage, like burial sites and rock paintings and provide us and future generations with glimpses of the past safeguarded from the homogenizing effects of the dot.com global village. Those who fund developments need to be made aware of social, cultural and environmental issues and where possible provide their funds for development that embraces sensitive design and integration of past and present elements be they artifacts of culture or designs of nature. Like other resources such as petroleum, all land containing a rich tapestry of biodiversity should be used as frugally as possible so that each may provide for our children’s children’s welfare; otherwise the sands of time are indeed running out for vegetation types like the Cape Flats Sandplain Fynbos. Photos: Milnerton Race Course – the most species rich site for Lowland Fynbos is experiencing extensive and encircling housing development. Century City – A Cape Flats Sandplain Fynbos, where 16ha of wetlands and its fringes were left undeveloped to form a Nature Reserve, but remains poorly integrated with the commercial hub. Most of UWC campus’s Sandplain Fynbos fall outside the current proclaimed nature reserve, but were originally included within it. Former protected Sandplain Fynbos is now available for new buildings and one has already been erected but its landscaping is poorly integrated with the natural vegetation.