Diagnosis of Varicella zoster infection and Review of Treatment

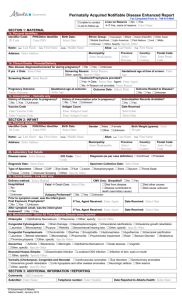

advertisement

Diagnosis of Varicella zoster infection and Review of Treatment Considerations for PostHerpetic Neuralgia in the Elderly Pamela Verma, BSc Hons1, Kuljit Dhaliwal MD2, and Dr. Nigel Walton, MB ChB MRCGP(UK) CCFP3 1 Corresponding Author: University of British Columbia Medical School, Class of 2012 308 East 34th Avenue ▪ Vancouver, BC ▪ V5W 1A1 pamverma@interchange.ubc.ca ▪ 604-322-6930 2 University of British Columbia, dkuljit@interchange.ubc.ca 3 Hollyburn Medical Centre, 307-575 16th Street ▪ West Vancouver, BC ▪ V7V 4Y1, drnigelgwalton@telus.net Key Words: Varicella zoster; post-herpetic neuralgia; anti-virals; aged; and Shingles 1 Abstract Herpes zoster infections are a common presentation seen in the primary care setting. Typically these infections are observed in children, although recent vaccination programs are reducing their presentation. In the elderly, and other immunocompromised states, re-activation of this infection, Varicella zoster can be seen. The infection results in a painful, erythematous vesicular rash that is dermatomally distributed. Although, most infections are self-limited, a major concern for health care practitioners is the subsequent “post-herpetic neuralgia”, an incredibly painful. This review presents a clinical case of a Varicella zoster infection in an 82-year-old man and evaluates current treatment modalities and evidence for prevention and treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia. Introduction Chicken pox is a well-known viral infection caused by Herpes zoster that typically affects young children (1). It is characterized by the presence of erythematous, pruritic, vesicular lesions. Infectious spread is through skin-to-skin contact and excoriation of the lesions can result in permanent scarring. The advent of a vaccination for the virus, routinely administered in Canada for patients above 12 months of age, will reduce the incidence of its presentation, but reactivation of this virus in formerly infected individuals remains a concern for clinicians (2). While routine vaccination for the pediatric population is now in effect (1), the disease burden will continue to challenge clinicians. Initial inoculation with the zoster virus is complicated by its reactivation, commonly referred to as “Shingles”. Triggers for this include stress, advanced age, and other immunocompromising factors, such as the co-infection with the human 2 immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (3). Interestingly, recent evidence suggests that there may be a genetic susceptibility to the reactivation of the virus in individuals (4). The disease burden of zoster in the elderly population is dramatic both in terms of patient suffering and health system costs. It is estimated there are 130, 000 new cases of zoster in Canada each year and 17, 000 cases of Post-herpetic neuralgia, with incidence dramatically increasing beyond the age of 60 years (5). Varicella zoster is typically diagnosed based on visual inspection of the characteristic lesion and its distribution. Latent viral particles reside in nerves, thus causing a dermatomal distribution of the lesions. Histopathologically, zoster lesions are indistinguishable from initial zoster infections, or the related Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection (6). Clinical presentation and history are used to distinguish these three herpes family infections (more). When the presentation is unclear, laboratory investigations can be utilized. Currently, investigations are being conducted to establish both skin (7) and salivary (8) testing for confirmation of the infection. Post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN) is a serious complication associated with the zoster infection with a potentially severe and prolonged course. PHN is defined as a persistence of pain associated with HZ, one month beyond the clearance of the dermatologic lesions: acute PHN (up to 30 days), subacute PHN (up to 4 months), and post-herpetic neuralgia (greater than 4 months) (9,9). Clinical Case 3 An 82-year-old Caucasian male had come to the clinic three days prior, complaining of a dull pain in left shoulder, and numbness in his left hand. This pain has been present for two weeks before the visit and initially was suspected to be angina pain because of its anatomic distribution. On follow-up three days later, his left arm pain had persisted. He described it as dull and continuous and its severity ranged from five to eight on a scale of ten. The pain had not been alleviated by regular strength aspirin, nor positioning. However, the pain was now associated with a vesicular rash that had appeared three days ago. The vesicles were surrounding by erythema, present in closely grouped clusters with a unilateral distribution on his left bicep and forearm (Figure 1). The primary treatment concerns were to manage the patient’s pain and prevent symptoms of Post-Herpetic Neuralgia. The patient was informed that condition is highly contagious, should avoid children not yet vaccinated against or exposed to the virus. The patient was asked to return for a follow up assessment. He was prescribed Valacyclovir (“Valtrex”, anti-viral) and Tylenol 3 (analgesic). Review of Treatment Options for Post Herpetic Neuralgia Anti-viral Therapies There is currently no evidence to demonstrate that Valacyclovir, Famciclovir, or Acyclovir prevents the incidence of PHN itself, these have been shown to minimize the duration of PHN pain (10). Tyring et al. (11) comparing Valacyclovir vs. Famciclovir, showed no difference in their ability to reduce PHN recovery time, however Valacylcovir was recommended due to its cost efficacy. Beutener et al. (12) also showed that Valacyclovir was 4 more effective than Acyclovir in reducing the duration of post-herpetic pain in a population of immunocompetent elderly (50 years or older). More specifically, the mean duration in Acyclovir group was 55 days compared to Valacyclovir given for 7 days (mean duration: 38 days) or 14 days (mean duration: 44 days). Based on the current literature, Valacyclovir appears to be an effective choice for the reduction of PHN symptoms for both its superior pharmacotherapeutic properties (compared to Acyclovir) and cost-efficacy (compared to Famcyclovir). Importantly, future research may be able to improve the options that are available clinically. For example, there was a very recent discovery of anti-varicella zoster virus activity of polyether antibiotic (13). Non-Antiviral Treatment Considerations Due to the inconclusive evidence for anti-viral medications in the treatment of post-herpetic neuralgia, a wealth of alternative treatment options have been investigated in the literature. Some alternate methods of treatment include using: anti-depressants, anti-convulsants, opioids, corticosteroids, and topical agents (9). Although many trials have been done there has been no conclusive evidence as to which form treatment is the most effective (9,14). The most current evidence for the efficacy of each class is reviewed below. Corticosteroids Corticosteroids are an anti-inflammatory class of drug historically prescribed for PHN, but current evidence has revealed that they do not significantly reduce the frequency of PHN (14,15). Other anti-inflammatory drug classes, such as ibuprofen, also appear ineffective (14-16). A 5 recent study conducted in Japan, revealed that intrathecal corticosteroid, in combination with lidocaine, significantly reduced both the incidence and duration of PHN (9). However, other treatment options are encouraged before intrathecal corticosteriods are indicated due to the significant associated side effects: major side effects included dyspepsia, nausea, and headache (16). Current Canadian standards of practice state that corticosteroids are not to be used for PHN treatment (10). Opioids The use of opioids in the management of PHN is not widely employed due to their addictive and other problematic side effects, such as constipation, sedation, and mental clouding (14). However, dosages indicated for PHN are far less than the threshold for the induction of psychogenic effects (9,14). Opioids act to inhibit the release of nocigenic transmitters in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, which is thought to provide pain relief (9). Morphine has shown better effects in reducing the incidence of PHN, compared to lidocaine (10). Both opioids and lidocaine are more effective than tricyclic (TCA) antidepressant therapy, but opioids have reduced side effects and were thus preferred by patients (17). Opioids have proven to be useful in elderly populations, where co-morbidities contraindicate the use of other drug classes for PHN treatment (14). Combining different drugs, such as oxycodone, in combination with acetaminophen or morphine has also been shown to achieve optimal effects (2). When prescribing opioids, it is best to also supply laxatives and stool softeners to prevent constipation (14,15). 6 Lidocaine The lidocaine (5%) dermal patch is commonly prescribed as an analgesic for PHN (9,14,18). It diffuses into skin and binds to dysfunctional sodium channels of damaged peripheral nerves, which are thought to reduce pain (9,18). While preliminary studies have reported positive outcomes, but more rigorous studies are necessary, for their use to become widely accepted (18). While both capsaicin and lidocaine do not yet have strong clinical support, they are promising because of their limited systemic absorption results in fewer adverse side effects (14). Anti-depressants Use of the tricyclic (TCA) class of anti-depressants in treating PHN is the current standard for pain relief, with strong evidence to support their use (14,19). At the low dose administered for PHN treatment, they work as analgesics, and not as anti-depressants (9). TCAs inhibit CNS reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin, and may also enhance inhibition of nociceptive signals from the periphery (9). However, their use is limited by their anti-cholinergic side effect profile including sedation, xerostomia, and even and cardiac dysrhythmias (at high doses) (14,20). Current studies encourage the use of nortriptyline and desipramine, over amitryptiline, because they have fewer side effects (10). Serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are better tolerated than TCAs, when administered for PHN; however more evidence is needed to explicitly demonstrate their efficacy in treating PHN (10,14,19). 7 Anti-Convulsants Anti-convulsant drugs are usually considered after unsuccessful trials of anti-depressants for treatment of PHN (9,10). This class of medications works by binding to voltage-gated calcium channels, reducing the release of excitatory neurotransmitters at the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, again thought to reduce central sensitivity and therefore decrease PHN (9,20). Gabapentin and pregabalin have both been shown to relieve the pain of PHN (14,15). However, pregabalin has a linear pharamacokinetic profile making its actions more predictable (2). Although, gabapentin has been shown to decrease pain, it is also associated with drowsiness, pre-syncope, and unsteady gait (9). A recent meta-analysis compared the effectiveness of anti-depressants (SSRI and TCA) and anticonvulsants (gabapentin) in treatment of PHN (20). Anti-depressants were shown to be more effective in prevention of PHN than anti-convulsants, however more patients are likely to discontinue anti-depressants due to their antimuscarinic effects of dry mouth, constipation, and blurred vision (20). Capsaicin Capsaicin, an alkaloid plant-derive, is a topical treatment used to provide moderate relief of PHN-pain (9,10,14). It is thought to enhance release of the nocigenic peptide, substance P, from C fibers, preventing their re-accumulation and ultimately causing depletion (9). Common side effects include burning (causalgia), stinging pain, and erythema on the site of application (9,14). Dosing plays an important role in efficacy: a recent study demonstrated that a 60 minute single 8 application of 8% capsaicin was more effective at providing pain relief up to 12 weeks compared to 0.5% used four times per day (21). Vaccines Recent investigations have explored the possibility of vaccination as a form of preventive therapy for PHN (14). The “Zostavax” vaccine was approve for the use of prevention of the herpes zoster infection for adults aged 60 years or over in August 2008. This decision was supported by a randomized controlled trial showed that the VZV vaccine reduced PHN incidence in an elderly population (defined as 60 years or older) by approximately two thirds (61.1%) (22). Vaccination is thought to prevent central sensitization by reducing the initial acute pain response as a means of reducing subsequent occurrence of PHN (22,23). However, further investigations are required to ensure the cost-efficacy and long-term health outcomes of this HZ vaccine (14). Currently, utilization rates (approx. 7%) are very low amongst eligible candidates, partly due to the cost of the vaccine ($150 CAD), which is not covered by the public health plan (5). Results and Discussion Treatment of PHN often requires multiple drugs and therefore requires a systematic approach (9,14). Current evidence suggests to begin treatment with the lowest dose an increasing the dose as appropriate and to choose medications that have limited adverse effects (9,14). Additionally, it is also recommended to use one medication from each class before using more than one medication from the same class (14). Early treatment of HZ with anti-virals is shown to decrease the risk of PHN from developing (14). 9 Back to the Case The patient was seen after two weeks, where his pain symptom and skin lesions were reassessed. The skin lesions were now crusted and had not erupted beyond the original dermatomal zone (Figure 2). The patient continued to complain of pain in his left arm and shoulder. He was offered a course of valcyclovir for prophylaxis against PHN and counseled about safety and disease transmission in the acute phase. Conclusion The growing burden of geriatric disease in Canada makes conditions like post-herpetic neuralgia most concerning. While the course of the zoster infection is acute, with severe but predictable symptoms, PHN can greatly escalate the care needs of an independently living elder. In addition to the work being done in the management of PHN with a known history of infection, efforts have also begun to focus on prevention. Prevention of Varicella zoster infectivity has been explored through the development of a vaccine that is given (reviewed (24)). Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank patient who was most cooperative in participating in this case report and enthusiastic for students to benefit from his experience. Figure Legend Figure 1. Unilateral grouped vesicles on an erythematous base in a dermatomal distribution on left A) arm B) forearm and C) bicep characteristic of herpes zoster infection. 10 Figure 2. Unilateral crusted papules and plaques on an erythematous base in a dermatomal distribution on left A) arm B) forearm and C) bicep characteristic of continuous herpes zoster infection. Figure 3. Unilateral grouped scarring plaques in a dermatomal distribution on A) arm B) forearm C) bicep associated with healing herpes zoster infection. References (1) Boivin G, Jovey R, Elliott CT, Patrick DM. Management and prevention of herpes zoster: A Canadian perspective. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2010 Spring;21(1):45-52. (2) Wootton SH, Law B, Tan B, Mozel M, Scheifele DW, Halperin S, et al. The epidemiology of children hospitalized with herpes zoster in Canada: Immunization Monitoring Program, Active (IMPACT), 1991-2005. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2008 Feb;27(2):112-118. (3) Reynolds MA, Chaves SS, Harpaz R, Lopez AS, Seward JF. The impact of the varicella vaccination program on herpes zoster epidemiology in the United States: a review. J Infect Dis 2008 Mar 1;197 Suppl 2:S224-7. (4) Hicks LD, Cook-Norris RH, Mendoza N, Madkan V, Arora A, Tyring SK. Family history as a risk factor for herpes zoster: a case-control study. Arch Dermatol 2008 May;144(5):603-608. (5) Watson CP. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. CMAJ 2010 Nov 9;182(16):17131714. (6) Steiner I, Kennedy PG, Pachner AR. The neurotropic herpes viruses: herpes simplex and varicella-zoster. Lancet Neurol 2007 Nov;6(11):1015-1028. (7) Sadaoka K, Okamoto S, Gomi Y, Tanimoto T, Ishikawa T, Yoshikawa T, et al. Measurement of varicella-zoster virus (VZV)-specific cell-mediated immunity: comparison between VZV skin test and interferon-gamma enzyme-linked immunospot assay. J Infect Dis 2008 Nov 1;198(9):1327-1333. (8) Mehta SK, Tyring SK, Gilden DH, Cohrs RJ, Leal MJ, Castro VA, et al. Varicella-zoster virus in the saliva of patients with herpes zoster. J Infect Dis 2008 Mar 1;197(5):654-657. 11 (9) Bajwa ZH, Ho CC. Herpetic neuralgia. Use of combination therapy for pain relief in acute and chronic herpes zoster. Geriatrics 2001 Dec;56(12):18-24. (10) Opstelten W, Eekhof J, Neven AK, Verheij T. Treatment of herpes zoster. Can Fam Physician 2008 Mar;54(3):373-377. (11) Tyring SK, Beutner KR, Tucker BA, Anderson WC, Crooks RJ. Antiviral therapy for herpes zoster: randomized, controlled clinical trial of valacyclovir and famciclovir therapy in immunocompetent patients 50 years and older. Arch Fam Med 2000 Sep-Oct;9(9):863-869. (12) Beutner KR, Friedman DJ, Forszpaniak C, Andersen PL, Wood MJ. Valaciclovir compared with acyclovir for improved therapy for herpes zoster in immunocompetent adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1995 Jul;39(7):1546-1553. (13) Yamagishi Y, Ueno C, Kato A, Kai H, Sasamura H, Ueno M, et al. Discovery of antivaricella zoster virus activity of polyether antibiotic CP-44161. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2009 Feb;62(2):89-93. (14) Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc 2009 Mar;84(3):274-280. (15) Schmader K. Herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med 2007 Aug;23(3):615-32, vii-viii. (16) He L, Zhang D, Zhou M, Zhu C. Corticosteroids for preventing postherpetic neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008 Jan 23;(1)(1):CD005582. (17) Raja SN, Haythornthwaite JA, Pappagallo M, Clark MR, Travison TG, Sabeen S, et al. Opioids versus antidepressants in postherpetic neuralgia: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurology 2002 Oct 8;59(7):1015-1021. (18) Khaliq W, Alam S, Puri N. Topical lidocaine for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007 Apr 18;(2)(2):CD004846. (19) Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007 Oct 17;(4)(4):CD005454. (20) Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuayHJ, Wiffen P. Antidepressants and anticonvulsants for diabetic neuropathy and postherpetic neuralgia: a quantitative systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2000 Dec;20(6):449-458. (21) Backonja M, Wallace MS, Blonsky ER, Cutler BJ, Malan P,Jr, Rauck R, et al. NGX-4010, a high-concentration capsaicin patch, for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a randomised, double-blind study. Lancet Neurol 2008 Dec;7(12):1106-1112. 12 (22) Steiner I. Can vaccinating older adults against varicella zoster virus prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia? Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2005 Nov;1(1):18-19. (23) Woolery WA. Herpes zoster virus vaccine. Geriatrics 2008 Oct;63(10):6-9. (24) Galea SA, Sweet A, Beninger P, Steinberg SP, Larussa PS, Gershon AA, et al. The safety profile of varicella vaccine: a 10-year review. J Infect Dis 2008 Mar 1;197 Suppl 2:S165-9. 13