Identity in Cyberspace - pete wardle digital artist

advertisement

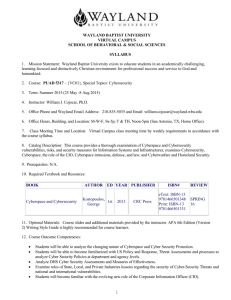

Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Our changing perception of our Selves by PETE WARDLE 1 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE CONTENTS Abstract.................................................................................................................................... 3 A Note on Terminology ............................................................................................................ 5 Definitions of Identity ............................................................................................................... 6 The influence of New Media on the ways we communicate ............................................... 8 Communication in Cyberspace .......................................................................................... 10 Factors influencing our identity in cyberspace ................................................................. 11 Changing Role of Identity in the 20th Century ................................................................... 14 Identifying Ourselves.............................................................................................................. 14 Identifying Others ................................................................................................................... 15 Constructing Identity - We can be whoever we want to be… or can we .......................... 19 Implications of new technology for the 'techno-body' and the real body ........................ 22 Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... 26 2 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Abstract This essay will analyse how the emergence of electronic media, from television onwards, has led to changes both in the way we perceive identity and in the nature of social interaction. It will look at how the use of cyberspace as a communications media has effected the ways in which we interact and consider the factors which influence how we portray ourselves in cyberspace not via a single coherent personality but by the expression of multiple identities. 3 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE “Sociology has long conceptualized persons as occupying multiple positions in organized sets of social relationships, and as playing out the diverse roles associated with those multiple positions” (Stryker & Burke 2000) “An identity is a set of meanings applied to the self in a social role or as a member of a social group that define who one is.” (Burke and Tully, 1977) “Although major stages of identity development are characterised by the integration of separate identity threads into a coherent whole and multiple identities are frequently thought of as a medical problem… it would appear that it is, at least to some extent, normal to have multiple adult identities…which fit the context in which they are operating. People have different identities associated with multiple roles. These roles are generally played out within differing physical or temporal spaces, leaving the choice of how much to reveal about the other identity to the individual who inhabits it.” (McAlpine, 2005) 4 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE A Note on Terminology Throughout this essay I use the term ‘Real Life’ to describe our primary physical lives as opposed to our non-physical existence in cyberspace and to any other physical identities we may manifest. This term is used rather than the term First Life (used by participants of Second Life to describe the same) as to use the latter would seem to imply ‘Second Life’ as an inclusive term for ‘all that which is not First Life’ which is not the case, i.e. using such terminology there is no appropriate description of nonSecond Life cyberspace existence. While it is acknowledged that a true definition of Real Life must include all our physical and cyber realities this essay will therefore limit the context in which it is used to refer only to our primary physical existence. 5 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Definitions of Identity While it is commonly believed that mentally healthy individuals exhibit a single, coherent personality which integrates all aspects of their identity, this is rarely if ever the case. Different facets of identity become dominant dependent upon a number of internal and external factors. Our personality is formed by how we perform in response to such factors and how others perceive such performances. Burke (2003) categories identities as being based upon one or more of three sets of circumstances; personal identities i.e. those based on one’s unique biological attributes or nurtured values. We may describe ourselves as fat, thin, short, tall, energetic, lazy, kind, selfish and may identify with any of these descriptions in a negative or positive way. social identities, i.e. those based on being members of groups; role identities i.e. those based on an individual undertaking certain pre-defined roles, e.g. as defined by our careers, family responsibilities, etc. Using terms popularised by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu it could be said that ‘Personal Identity’ is one of Agency, ie. the acts of individuals made independently under free will, while the ‘Social identities’ and ‘Role identities’ are Structural, i.e. in response to factors such as expectations and contraints imposed by society such as social codes and conventions, class, religion, gender, ethnicity, etc. In Huxley’s vision the roles of the lower class Delta labourers are entirely Structurally defined, prescribed for them by the Brave New World in which they exist. However it is clear that that there is Agency implicit in our Social and Role Identities, insofar as we ultimately choose, whether conciously or otherwise, our careers, social and family circumstances, just as it would be naïve to beleive that our personal identities are not influenced by our responses to society around us. For example, societies dubbing an individual overweight may lead to such individual to develop Personal Identity attributes such as shyness, or to take action to lose weight, or may have no discernable effect. The colour of an individual’s skin may not only affect the individual’s Personal Identity but also their Social and Role identities. The work of Bourdieu was particularly prominent in emphasising that, despite apparent freedom of choice in such areas as mucical preference (e.g. classical, rock, folk), such choices are strongly influenced by an individual’s social background and position. Further he evidenced that personal qualities influenced by an individuals upbringing, eg. Accent, style, are often major factors in their career and status in later life. 6 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE We might also equate these three modes of identity as equivalent to the framework of modalities, Having, Being and Doing, identified in The ‘Exchange Theory’ ( Foa & Foa, 1971, revised by L'Abate, Sloan, Wagner, & Malone). Our personal identity can defined by what we have, eg. Brown hair, white skin, and further extends to include our belongings, eg., one might have, or desire to have, a large house, fast car or designer wardrobe. Our social identity becomes defined by who we are, eg. A supporter of a particular football team, a member of a political party, a college teacher. Our role identity becomes defined by what we do, and semantically suggests absorbtion into our role, eg. We swim, we dance, we teach. One may, for example, wish to become a writer, a Social Identity. The only way to achieve this is to absorb themselves in the process of writing, and in doing so define for themselves a Role Identity. This definition of the Role Identity as ‘doing’, corresponds with the philosphy of Neitzche who argues that “there is no I” i.e. there is no separation between the do-er and the deed. 7 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE The influence of New Media on the ways we communicate Marshall McLuhan (1964) highlighted the effects which the introduction of new forms of media had on society; “Every new form of media is an extension of the human body. The book is an extension of the eye. The wheel is an extension of the foot. Clothing is an extension of the skin.” It follows that as our body is extended, so is our perception of identity. We identify with, or rather assimilate into our identity, what we read, what we drive, what we wear and, of particular relevance to this essay, the methods we use to communicate with each other. “A man's identity is not best thought of as the way in which he is separated from his fellows but the way in which he is united with them.” Robert Terwilliger Director, Trinity Institute, NYC McLuhan recognised how our society had changed radically with the introduction of the visual language of writing and the further widespread impact following the introduction of the printing press. Influenced by McLuhan Neil Postman (1985) went further quoting Marx’s ‘German Ideology’; “Is it not inevitable that with the emergence of the press the singing and the telling of the muse cease; that is, the conditions necessary for epic poetry disappear.” Postman further commented on the effect of both telegraphy and television upon society; “For the first time in human history people were faced with the problem of information glut... we were sent information which answered no question we had asked and which, in any case, did not permit the right of reply.” In brief we had become a society based upon passive consumption of information. It can now be seen that the introduction of newer forms of media have created further and increasingly faster changes in our methods of communicating. The diagram below shows how technologies have been integral to the swing of societal preferences not only between the oral and the typographic, but also between active two way communication and passive consumption. 8 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Technology Oral/Typographic Active/Passive Conversation and storytelling Oral Active The printed word Typographic Passive Telephony Oral Active Television Oral Passive Web Typographic Passive Email, chat rooms Typographic Active (but with delay) Messaging services Typographic Active WebCams, Voice in Second Life Oral Active The above is a simplification of the true position. Both Foucault and Baudrillard wrote of our active/passive relationship with film and television respectively and it is noted that a passive viewer might be considered to be actively responding by assigning meaning to the transmitted content. However, even if the viewer is active in this way the relationship must still be considered passive as the actions of the viewer have no immediate link to the subsequently transmitted communication. Truly active communication media, when viewed in McLuhan’s terms as an extension of our selves, have a particularly significance as it is through them that we create a two way interface with those who in turn influence or consolidate our identities. 9 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Communication in Cyberspace The psychologist John Suler has written extensively on how we communicate differently over digital media than we would were we using other forms of communication, particularly the tendency for deviant behaviour, or deviant identities, to manifest in cyberspace due to the effects of ‘disinhibition.’ “ Sometimes people share very personal things about themselves. They reveal secret emotions, fears, wishes, show unusual acts of kindness and generosity, and as a result intimacy develops... On the other hand, the disinhibition effect may not be so benign. Out spills rude language, harsh criticisms, anger, hatred, even threats.” He lists the following as reasons for the ‘disinhibition effect;’ reduced sensation - Absence of face-to-face cues asynchronous communication - people may take minutes, hours, days, or even months to reply to something you say and we need not therefore deal with any adverse reaction to what we say immediately. Conversely receiving no immediate reply from digital companion may make wonder did they have said something wrong and are being snubbed. Anonymity - most of the people you encounter can't easily tell who you are and your accountability is therefore limited. Invisibility – the option in many digital environments to watch and monitor others before choosing to reveal your presence Neutralizing of status – the effect of the internet to make all appear as equals regardless of any perceived standing in Real Life Suler lists a further reason to be Solipsistic Introjection, or the fact that the writer feels the conversation is actually taking place in their head rather than in a more widely shared reality. Moreover it may be speculated that the writer, and perhaps the reader too, feels that the conversation is taking place in a consensually shared fantasy and that the reader, by the act of reading, has ‘bought into’ the fantasy of the writer and therefore subject to the writer’s rules. To borrow the words of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, these fantasies contain within them “a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief.” One must ask how close this is to matching the vision of William Gibson (1984), the creator of the term ‘cyberspace,’ who wrote of ‘disembodied consciousness’ being projected into ‘the consensual hallucination known as the matrix.’ Disinihibition is common regardless of the recordability of internet conversation and can lead to an over familiarity in digital relationships which may or may not continue into any Real Life relationships which might ensue. 10 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE What factors comprise our identity in cyberspace “Identities are identified by identifiers. Some identifiers require the authentication of the entity whereas some identities can be authenticated by uniforms, passwords, secret hand-shakes or other identifiers which do not expose the entity behind the identity.” Ito, J Multiple factors can be considered to take a part in defining one’s identity at any given time; the way we dress, speak, our political views, the ephemera with which we surround ourselves, or as in Hershman’s work ‘Dante Hotel,’ discard, or the physicality of our interaction with others, e.g. the identity as an individual as a teacher is reinforced by the physicality of standing in front of the class, the identity of the student reinforced by sitting at a desk amongst rows of other desks. Foucault wrote of how ‘physical mechanisms’ such as the ‘cellular distribution of bodies’ such as found in schools, factories and monastic cells assists in creating a discipline which allows authority to “construct docile bodies.” However in cyberspace our identity is no longer subject to such conventional restraints. In McLuhan’s terms Cyberspace may simply be an extension of our communicative faculties, however it might equally be seen to offer an extension of our identities. Such digital identities can be constructed as carefully, or carelessly, as our physical identities. What goes into creating one’s digital identity/s is in many ways a reflection of those things which go into creating our conventional identities; Our names; in Real Life, we may choose to call ourselves by different names on different occasions by utilising titles, nicknames, etc. The names we are called by others as children, e.g. our parents or our contemporaries at school can hold power over us just as the names we call ourselves can hold power over others. The use of a middle initial may infer seniority as in Harry S Truman or George W. Bush. In most digital environments we are at liberty to choose any name we wish, however it is interesting that within Second Life, while users can choose any first names they are limited to a pre-defined list of surnames. Our addresses; Marketing companies, insurance companies, etc, may define our social standing by the postcode at which we reside. In cyberspace everyone becomes equal, but the addresses we choose to use still say something about us. People may, for instance, doubt the authenticity of a hotmail address and the use of a middle initial in an email address can lead to the recipient categorising it as spam. What we say; perhaps even more crucial in cyberspace than in Real Life due to the fact that generally, what we say in cyberspace is recordable. Nonetheless, participants in cyberspace seem to 11 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE subscribe to an illusion of privacy and treat digital communication with an undeserved levity and disregard for the fact that others may read it. What is said about us; In cyberspace any individually constructed identity may or may not be easily traceable to its ‘owner.’ In any case, what is said about any of our identities influences the way people will view that identity and react to it. In his recent Guardian column Jon Ronson recounted how once, following the release of Paul McCartney’s Frog Chorus, he had written in an article that the wrong Beatle had been shot, only to realise the impact of his actions upon receiving a letter from Linda asking him if he really meant to advocate the murder of her husband and father of her children. He went on to compare this to the phenomena of blogs, forums and chat rooms which turn us all into published writers who, without perceived accountability, can casually demean the Real Life or virtual actions of others. The places we go; the sites we visit, the forums and groups to which we subscribe, the shops we visit and the items we buy, all help form a part of our digital identity or identities. Amazon and other stores base their business upon tracking this kind of information and offering us products and services based upon the digital trails we leave. Our circle of friends; Cyberspace friends fall easily into two categories; the ones we have met and interact with in Real Life, and those who we have met only digitally. It is becoming increasing common for individuals to have more friends in the latter category than the former. However, while it is far from unknown for marriages to take place between individuals whose relationships began on the internet, cyber- friends are often seen as more expendable than their Real Life counterparts. David Birch writes “research (by Danah Boyd) in the US has confirmed … that young persons who forget their MySpace password are just as likely to make a new account as fret over their lost friends… an online profile is not seen as something to build an extensive identity around, but something to use to talk to friends in the moment’” Our avatars; Avatars are a particularly powerful and personal graphical representation of identity which individuals construct consciously and carefully. Avatars are integral to the construction of a digital identity as represented through chat rooms, forums and environments such as Second Life. As visual representations they are a key determining factor in how people perceive the identity we are promoting. While they could be compared to the clothing we wear in Real Life, they are much more than this. They are the bodies we wear in cyberspace. What we share; With sites such as Youtube, Flickr and Facebook growing in popularity we are able to share aspects of our Real Life personality within cyberspace. This, more than any other, becomes the defining boundary between Real Life and cyberspace, a point at which, if we allow it, the most intimate aspects of our Real Life identity become publicly available. However the inherent dangers are clear. Not only do we risk breaking down the boundaries between carefully constructed identities in both Real Life and cyberspace, we also put our trust in the identities shared on these 12 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE sites by others without consideration that, like Hershman’s Roberta, they could be carefully constructed fakes. In many respects the identities we construct in cyberspace need no authentication as in casual cyber conversation it hardly matters whether we are who we say we are and it is generally accepted that we may, in fact, not be. There is a trend for individuals encountering new people on cyberspace to immediately inquire as to their ASL (age, sex, location), in an attempt to classify that which lies beneath the visible constructed identity, without apparent realisation that whatever response is given can just as easily be a description of a constructed identity. A request for ASL therefore constitutes little more than a hopeful plea that the respondent might allow a true glimpse at the ‘authentic’ identity beneath. True authentication of identity is different from the other aspects of identity in so far as it is not, generally speaking, constructed either intentionally or by behaviour patterns, but rather is a way of authenticating the digital self’s transactions in the physical world. Jo Ito writes; “It is essential to consider the issue of identity independently from the issue of authentication of the entity. When one is engaging in a transaction with some identity, one is concerned with the risks and attributes of the identity with respect to the transaction. When one is trying to sell diamonds, one is concerned with the authentication of the other identity’s financial attributes. If one is trying to receive donated blood, one is concerned, not with who it came from, but the type and whether it is safe. If one is selling liquor, one is concerned with the age of the purchaser, not the address.” The digital age has given birth not only to a multitude of new methods to track and authenticate identity for purposes of both security and marketing, with the arrival of such techniques as digital signatures and biometric identification, but has given rise to previously unheard of terms, and crimes, as identity theft. 13 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Changing Role of Identity in the 20th Century “The pretence of being another person, or a number of other people, is a precondition of electronic access.” Lynn Hershman Leeson Identifying Ourselves The growth of advertising in the twentieth century first through the medium of print, and then radio and television, encouraged identification with ‘Having’, that is to say identifying our Selves with our possessions, leading to the preoccupation of many with ‘keeping up with the Jones’s,’ a phrase coined in 1913 by cartoonist Arthur R. "Pop" Momand . (Hendrickson, R). In McLuhan’s terms these possessions could be viewed as extensions of our body, though in actuality they are much more extensions of our identity. Postman (1985) writes of this phenomena; “Who would have suspected the automobile would tell us how to conduct our social and sexual lives… would create new ways of expressing our personal identity and social standing?” The example of automobiles is an interesting one. In the middle of the 20th century there was a tendency for individuals to identify with there cars as separate entities which they would give names in the same way one may treat a family pet, which can be assigned to the mode of ‘having’. However by the time of Postman’s writing this practice was becoming less common, to be was replaced by the tendency for individuals to personalise the number plates of their vehicles as an expression of their name, career or personality, i.e. directly identifying the vehicle with themselves, which can be assigned to the mode of ‘Being’. As our possessions become extensions of ourselves, technology supports further evolution of our facilities in the form of cameras and monitoring equipment to allow us to monitor these extended selves. Only when we absorb ourselves in our actions entirely do we truly identify ourselves with Doing and in the realisation of this identification it ends. When one drives a car, they simply perform the act of driving, of Doing. When one realises ‘they’ are driving, they see themselves as ‘a driver’, a state of Being. 14 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE In modern society it is easy to create a record of what we have done, and so identify our selves with this archive, confusing the recording of Doing with the act of Doing itself. No longer limited to scrapbooks and albums the web offers a wide range of ways by which we may not only preserve a record of our Doing, but present it to other in the form of websites, blogs, photo albums, youtube videos, deviant art, etc, everyone competing for their ‘five minutes of fame.’ The same people who present this information also act as voyeurs, hungry to view similar information from others, and feel they are participating in the Doing of others, some of whom they may never even have met. A manifestation of this is the popularity of ‘fly on the wall’ TV shows such as Big Brother. Baudrillard writes of the effects of the precursor to such shows when in 1971 the Loud family disintegrated during a seven month American filming experiment. Postman anticipated the modern equivalent when he wrote; “In the Huxleyan Prophecy Big Brother does not watch us , by his choice. We watch him, by ours. There is no need for wardens or gates or Ministries of Truth. When a population becomes distracted by trivia, when …in short a people becomes an audience and their public business becomes a vaudeville act… culture death is a clear possibility.” Identifying Others “There is always an assumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what is in the picture.” Sontag (2001) This may have once been true, but with the emergence of New Media photographic manipulation has become so commonplace that such an assumption is no longer possible. Even in the early days of photography, artists subverted medium to express the concept of alternative identities. An early example of this is Duchamp's photographs of himself in drag as Rrose Sélavy. Many artists since have used photography as a medium through which to express ideas of identity, notably Cindy Sherman, whose career has been based a succession of photographs, using herself as the model. Rochelle Steiner wrote of her;“because Sherman takes on different personas for her photographs she cannot be identified in them.” She quotes art critic Craig Owens in saying; “the significance of Sherman’s work resides in the artist’s permutations of identity from one photograph to the next.” 15 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Television however changed forever the way in which a wider public viewed identity. For the first time the public was confronted with a situation whereby the individuals they encountered most frequently, and whose lives became most intimate to them, were fictional. A tendency emerged for people to feel that they actually knew the character on screen, and further to identify, or even confuse, the actor with the character being played. This led to actors becoming typecast, renown for a single character, or type of character, but failing to secure a wider range of roles. When actors left a role which they had made their own, producers had to develop strategies to assist the public in making a transition to a new actor assuming the identity of the character. Often this worked best when the transition was both highly publicised and when the new actor presented a markedly different characterisation of the fictionalised identity. Today, for example, it is not uncommon for individuals to be able to list all of the actors who have played James Bond. One of the most creative examples of such a transition was in 1966 when Dr. Who producer Innes Lloyd chose Patrick Troughton to replace the William Hartnell in the lead role. Troughton was in no way similar to his predecessor, an issue which was resolved by a plot device to allow not only the identity of the actor to change, but also the identity of the character to undergo dramatic transformation. The idea of a single role being expressed by a number of individuals is not unique to the field of acting. It echoes much older institutions, for example the role of a King or Pope. The idea was been taken up in the 1970s by artist Lynn Hershman Leeson’s creation of Roberta Breitmore, a persona she adopted. On her website Hershman says; “Many people assumed I was ROBERTA. Although I denied it at the time and insisted that she was "her own woman" with defined needs, ambitions and instincts, in retrospect we were linked. ROBERTA represented part of me as surely as we all have within us an underside; a dark, shadowy anaemous cadaever that is the gnawing decay of our bodies, the sustaining growth of death that we try with pathetic illusion to camouflage . To me, she was my own flipped effigy; my physical reverse, my psychological fears. As can be inferred from the records of both of us, her life infected mine.” Hershman’s Roberta 16 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Hershman lived Roberta’s life and masses of information, documentation and ephemera were generated to authenticate Roberta’s existence. However Hershman also employed other actors to take on the identity of Roberta. Alvarez (2003) writes; “Roberta was a virtual clone of Leeson that took on a life of its own – in fact, three lives. In the second year of Roberta’s life her adventures became so numerous that she grew into a multiple; Leeson ended up hiring three separate actresses to "perform" Roberta.” However unlike the actors who played Dr. Who and James Bond, these actresses tried to represent the same ‘authentic’ Roberta as Hershman. The artist herself spoke at the Autonomous Agents Symposium (Manchester, 2006) of “authenticity being only ephemeral.” The photographic and video work of Alison Jackson uses the codes and conventions of the hidden camera to subvert the ideas inherent in identity and celebrity. In her work she uses look alike actors to assume the identity of celebrities and public figures in private, often embarrassing, situations, to convince the public that they are viewing not a look alike, but are taking an authentic look at a ‘private’ event in the life of the celebrity, even to question what they know of that celebrity’s reality as in the picture below representing the child of Princess Diana and Dodi Fayed . Alison Jackson’s Dodi & Diana The ‘Real’ Lara? The character Lara Croft, heroine of the Tomb Raider Game released by Eidos in 1996 is a commercial example of a character which has been portrayed by a number of individuals, each of which has attempted to be faithful to the authentic original. The difference in this instance is that the ‘authentic’ Lara is not portrayed by an actress, but rather is an entirely digital creation. As well as the actress appearing in the movie adaptation, Angelina Jolie, Eidos have cast a succession of "real-life" Laras to act as an ambassador for the Tomb Raider brand, appear on chat shows and embody the ‘essential’ Lara. 17 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Baulillard wrote; “simulation threatens the difference between the ‘true’ and the ‘false,’ the ‘real’ and the ‘imaginary.’ Lara Croft is such an example of the blurring distinction between a digital ‘imaginary’ character and a ‘real’ character. Is the ‘real’ Lara the digital original or the current flesh & blood copy? Over a decade earlier, Channel 4’s ‘Max Headroom Show’ raised similar questions with the introduction of the title character, a purportedly ‘futuristic digitally-generated’ character, portrayed by real actor Matt Frewer, recently revived for a series of Channel 4 adverts promoting digital television. The relationship between real and digital portrayals of identity become even more blurred when we consider digital characters whose movements are based upon the Real Life performances of actors such as is the case with Andy Serkis’s performance of Gollum in the Lord of the Rings trilogy of movies. New questions begin to arise; can a digital performance such as this be nominated for existing performance award categories? In 2002 Wired magazine wrote; “If an actor can alter his face with makeup and still get nominated for awards, why can't someone who alters his appearance with digital pixels?... every sick smile of Gollum's, every scampering movement, was created by the actor and then recreated digitally… It's like applying makeup after the fact, only the overlay isn't with latex before the performance. It's after the performance with computers," Serkis told the Associated Press recently.” Perhaps more important is the unresolved issue of ownership, i.e. does ownership of the physical performance still reside with the actor following digitisation? San Francisco Chronicle pop culture critic James Sullivan wrote; "In an age of stem-cell research, digital imaging, advanced robotics, and fabrications that are often more dear to our hearts than real people, at what point do the products of human creativity declare independence from their creators?" 18 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Constructing Identity - We can be whoever we want to be… or can we “(Some) groups in cyberspace encourage or even require that you assume an imaginary persona... You could get away with pretending to be someone very different than who you are, or you could alter just a few features - like your name, occupation, or physical appearance - while retaining your other true characteristics. No one will know.” Suler McAlpine (2005) was earlier quoted as discussing how multiple identities are generally ‘played out within differing physical or temporal spaces.’ In communication via digital media this is no longer true. We are permitted the opportunity to hold many conversations, and juggle multiple identities, simultaneously. Furthermore we have more opportunity to construct these identities than ever before and, once constructed we no longer see ourselves as ‘having’ ownership of these identities, but rather as ‘being’ them or identifying with the acts they are performing (doing.) Donna Haraway saw how high tech culture could challenge dualisms persistent in Western tradition such as self/other, mind/body, writing; “Any objects or persons can be reasonably thought of in terms of disassembly and reassembly; no 'natural' architectures constrain system design… It means both building and destroying machines, identities, categories, relationships.” An interesting phenomenon is that of digital ‘gender switching.’ Sadie Plant described identity as “not the goal but the enemy, precisely what has kept at bay the matrix of potentialities.” With the construction of digital identities, even factors such as gender are no longer constraints. While the practice attracts less controversy than its Real Life counterpart, its motives may be similar, e.g. the desires to explore emotional characteristics of the opposite sex, or same sex relationships, which individuals may feel to be difficult in Real Life. Of course, this is not always the case - in multiplayer games a male player becoming a female character may be advantageous to procure more assistance and progress faster in the game. Other hidden aspects of oneself may emerge in a digitally constructed identity. According to Suler; “How we decide to present ourselves in cyberspace isn't always a purely conscious choice. Some aspects of identity are hidden below the surface. Covert wishes and inclinations leak out... A person selects a username or avatar on a whim, because it appeals to him, without fully understanding the deeper symbolic meanings of that choice.” 19 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE While cyberspace offers us an environment to create ourselves and our identities anew, we may just as easily find ourselves falling into existing patterns of behaviour and replicating our conventional relationships. It can be questioned whether any identity we create for ourselves can display characteristics that are not already present in the creator. However they can be constructed using elements of the individual that would normally be hidden. Turkle writes; "We do not feel compelled to rank or judge the elements of our multiplicity. We do not feel compelled to exclude what does not fit." Once constructed, as with Hershman’s Roberta, their reactions to external stimuli might be viewed to be autonomous. Individuals are free to indulge their fantasies. However they must be aware that even in cyberspace their actions may have consequences, for themselves or others with whom they interact. In Second Life adult players may choose for avatars to depict children, even form part of virtual familys.While this may have no sexual motivation, others indulge in "Age Play", in which adult players participate in virtual sex with other adults using child avatars. In Germany such practices constitute virtual child pornography, punishable by up to five years in prison. Second Life is of course not unique in this. Traditional and deviant sexual practices are rife in cyberspace. Even before the rapid growth of cybersex, Haraway wrote; “Ideologies of sexual reproduction can no longer reasonably call on notions of sex and sex role as organic aspects in natural objects like organisms and families.” Opponents argue cybersex is wrong, that it is anonymous, superficial, artificial, unnatural. These are perhaps the very characteristics that add to its appeal. Online groups such as Fake.swedma.com are based on the premise that users can express fake identities, but swiftly evolve into meeting places for those seeking cybersex. There is no denying the inherent dangers of cybersex for adolescents who may become targets of adult predators while the reverse may also be true, with documented cases of adolescents who pretend to be older in order to flirt with unsuspecting adults. While under 18 year olds are prohibited from taking part in Second Life or Fake, it is in practice impossible to effectively check the ages of all participants but regardless of its dangers and detractors cybersex is a growth phenomenon. Second Life features shops devoted to sexual items, services, and avatar bodies. Cybersex has given rise to groups such as nerverts, described by Mieskowski as those who manifest [the] convergence of computer nerd and weird sex. As Suler writes; “Sex always sells, in real or virtual life.” 20 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE If cybersex allows individuals to participate in fantasies that would otherwise be prohibited to them, where then, if anywhere, is the line to be drawn? There are already examples of the development of sweat shops in Second Life, slavery exists albeit, so far, only in the form of consensual sex slavery. Will the future see ‘virtual murder’ where individuals are able to eradicate the carefully constructed digital identity of another and, if so, will this be deemed a crime in Real Life? However, regardless of the prominence of ‘deviant behaviour’, it is not always the reason for creating a digital identity. Forums and cybercultures exist for almost every interest group. Suler writes; adolescents are drawn to cyberspace because they make friends there. Cyberspace technology excels in all sorts of methods for forming groups - and adolescents take advantage of it because joining and shaping a new group is so important to their evolving identity. What do they do once they're in the group? They joke and play games, complain about their parents and teachers, talk about their lives, support and give advice to each other... the same things they do in "real" life. However, as with groups in Real Life, there is a tendency for groups to identify with only a single element within an individual’s identity, eg. race, religion, sexuality, politics, and in doing so elevate it to a disproportionate importance, e.g., gay men subscribing to forums such as Gaydar, may come to view and describe themselves solely in terms of their sexuality rather than seeing sexuality as an aspect of a more complex identity structure. 21 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Implications of new technology for the 'techno-body' and the real body Rene Descartes theorised that the mind was more real than the body in which it is housed. We may ask then if, through our journeys into cyberspace, we are evolving to a stage where our virtual lives will replace our Real Lives, or indeed if this is already the case? Suler asks: “What is one's TRUE identity? We usually assume it must be the self that you present to others and consciously experience in your day-to-day living. But is that the true self? Many people walk around in their f2f lives wearing "masks" that are quite different than how they think and feel internally…Our daydreams and fantasies often reveal hidden aspects of what we need or wish to be. If people drop the usual f2f persona and bring to life online those hidden or fantasied identities, might not that be in some ways MORE true or real?” Indeed there may be instances where it is unclear whether we are interacting with a ‘true’ individual or a machine, such as is the case on Agent Ruby’s edream portal created by Hershman, as with certain Bots in MUDs and Second Life. Moreover Dr. Rudolfo Llinas, Professor of Neuroscience, contends that Real Life itself is no more than a structure of imagination: 'Basically, the brain is a dreaming machine. It is the brain that generates reality.’ Turkle (1997) presents a possible answer; “Since everything is surfaces to be explored, and no surface has any more legitimacy than any other, the "embodied" life we live on a day-to-day basis has no more reality than the role-playing games on the Internet …MUD players can develop a way of thinking in which life is made up of many windows and RL (Real Life) is only one of them." Turkle cites Lacan with a "more radical decentering" of the self and the"portray[al] of the self as a realm of discourse rather than as a real thing or a permanent structure of the mind." It is evident though that digital life cannot offer all the same satisfactions as Real Life. Getafirstlife.com humorously promotes the benefits of RL; “Fornicate using your actual genitals!” Suler writes of the limitations of text relationships but his comments may apply equally to any online relationship; “LOL and [[Joe]] are textual representations of a laugh and a hug for Joe, but they are NOT the laugh and the hug. What are the implications of interacting with textual representations but not 22 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE with the actual physical and bodily experiences? How does the psychological and emotional impact of typing an LOL or even the abstractly raucous ROFL compare to the actual experience of rolling on the floor laughing? Does a text hug sink in the same way as actually feeling someone's arms around you?” One advantage of cyberspace is that it can create virtual environments which, while they may choose to copy reality have no requirement to do so. Predicted by the Holodecks in Star Trek, immersive virtual realities could be used to give a historical tour of ancient Greece, or to take one into uncharted fantasy realms. Immersive usually taken to mean full ‘physical’ immersion however it is evident that to become immersed in a virtual environment, whether Second Life, game play or a movie does not rely upon this. Full immersion may in fact lead to unpredicted changes in the personality. Cars, for example, provide a closed, immersive, environment in which otherwise meek personalities become aggressive towards other drivers, exhibiting the characteristics of ‘a different person behind the wheel.’ The American army is currently developing hi-tech armour which provides an immersive environment for the wearer and encourages focussed aggression. In most cases where we construct identities and relationships a screen suffices provided no glitches occur to jar the ‘us’ from our immersion. Manovich talks of the screen as ‘a window into another space’ which; ‘doubles the viewing subject who now exists in two spaces: the familiar physical space of his/her real body and the virtual space of an image within the screen. This split comes to the surface with VR, but it already exists with painting and other dioptric arts.” “Perhaps hundreds of years from now, media historians will consider TV and movies the earliest forms of VR.” (Suler) Artists are currently working with the idea of avatars becoming individual entities such as Paul Sermon’s Real Life/Second Life interactive installation, Liberate your avatar where Real Life visitors and Second Life avatars were brought together to share the same park bench. Hershman’s Roberta appears as an avatar within Second Life reminding us of Foucault writing of the image of the monarchs unseen but as reflections in the mirror in Las Meninas; a representation of a representation. Similarly there is nothing to prevent an avatar, or rather the constructed identity it represents, promoting themselves and their relationships using on Facebook. 23 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Roberta (left), Las Meninas (right) One potential issue is that of ‘authentication’ of constructed identities insofar as there is no guarantee that the avatar with whom we interact is being ‘operated’ by the same individual each time we meet. Similarly any one of multiple people could be responding to using a single email address, msn identity or even mobile phone. Ultimately we must decide for ourselves whether this is of concern or if we are happy taking the digital identity with whom we interact on its face value. Digital life brings with it other new problems to be addressed; Disintegrating boundaries between our identities are reflected in increasingly blurred distinction between our work and leisure lives; while doctors are still researching into the phenomena of addiction to video games, particularly multi-user online games, many manifestations of compulsive behaviour are more subtly pervasive. Unnecessarily frequent checking of email is common, as is invisible monitoring of chat rooms to check who is there Not only is our physical existence under almost constant CCTV surveillance, our digital identities too are monitored with our tacit or explicit agreement. Chat room monitors can read our ‘private’ conversations while anyone can log onto Facebook to see our most personal events. Cookies from shopping sites such as Amazon monitor our purchases and adware monitors which sites we visit. In cyberspace we find ourselves able to participate in activities which parallel new developments in Real Life and lead to moral or philosophical debate. We seek to change the perception of our identities by modification of our bodies. Cosmetic surgery has never been more popular and artists such as Stelarc work extensively with implants. While this is happening in Real Life, cyberspace frees us to modify our avatar bodies as we will. Scientists are working to develop neural interfaces which will allow paraplegics to operate computers to transcend the boundaries of their physical capabilities. In cyberspace such transcendence is of the physical already allows us to soar high above the cities of Second Life or City of Heroes. Cloning raises the question whether one person can exist in two places at one. Cyberspace allows us to simultaneously coexist in one physical reality and multiple digital realities. 24 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Modification of the genetic code may allow parents to choose to eradicate disabilities, or other attributes they may consider undesirable, in children at the point of conception, constructing new life in the way that parallels the choices we make when constructing identities in cyberspace. Detractors from the potential of science may see the above as examples of man playing god. Must we therefore question whether there is any moral difference between the physical developments and their virtual counterparts? Haraway wrote of technology as challenging the duality between god and man. Reminiscent of the Matrix movie Suler proposes that through cyberspace “we have entered the next stage in the expression of what it means to be human.” If this is true, given our unprecedented freedom to construct and direct the evolution of our identities, we might better ask if we are becoming the intelligences behind our own intelligent design. 25 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE Bibliography Alvarez, D, The Frankinstein Syndrome’ 21/7/2003 Filmakermagazine.com Birch, David http://digitaldebateblogs.typepad.com/digital_identity/2007/01/age_vs_identiti.html Brinberg, D & Wood, R, (1983) A Resource Exchange Theory Analysis of Consumer Behavior, The Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 10, No. 3., pp. 330-338 available on JStor Buadrillard, J, Simulcra and Simulation, Selected Writings, ed. Mark Poster (Stanford; Stanford University Press, 1988), pp.166-184 also available from http://www.egs.edu translated by Sheila Faria Glaser Burke, P. J., and Tully, J. C. (1977). The Measurement of Role Identity. Burke, Peter J. (2003) “Relationships among multiple identities” available from http://wat2146.ucr.edu/Papers/03d.pdf Burke, Peter J. (2007) Identity Control Theory available from http://wat2146.ucr.edu/Papers/05d.pdf Foa, EB & Foa, UG 1974, Resource Exchange Theory Foucault, M, Discipline and Punish (trans by Sheridan, A) Penguin Books Ltd; New Ed edition (1991) Gibson, William, 1984,Neuromancer, Phantasia Press Grieb, M, (2003) Transformations of the (Silver) Screen: Film after New Media, University of Florida Hendrickson, Robert, The Encyclopedia of Word and Phrase Origins, Checkmark Books; 3Rev Ed edition (2004) Hershman, Lynn - http://www.lynnhershman.com and Autonomous Agents Symposium at Whitworth Gallery Manchester on 22nd November 2007 http://www.csa.com/discoveryguides/perform/overview.php http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2007/may/08/secondlife.web20 http://www.wired.com/entertainment/music/news/2002/12/57012 Ito, J, Identity and Privacy in a Globalized Community available at http://www.aec.at/en/archiv_files/20021/E2002_244.pdf Jackson, Alison (images) available at http://www.alisonjackson.com L’Abate L & B 1981, The Dream and the Reality; Family Relations, Vol. 30, No. 1. (Jan., 1981), pp. 131-136 available on Jstor 26 Pete Wardle Technoculture: IDENTITY IN CYBERSPACE L'Abate, L, 1994, A Theory of Personality Development 1994, John Wiley and Sons Manovich, L, 2001, Language of New Media, MIT Press; McAlpine, Mhairi, E–Learning, Volume 2, Number 4, 2005, E-portfolios and Digital Identity available from http://www.wwwords.co.uk/pdf/viewpdf.asp?j=elea&vol=2&issue=4&year=2005&article=7 McAlpine_ELEA_2_4_web&id=82.22.114.199 McLuhan, M, 1964, Understanding Media MIT Press; New Ed edition (1994) Mieskowski, Katherine quoted by Borsook, Paulina, 2000,Cyberselfish: A Critical Romp Through the Terribly Libertarian Culture of High-Tech Nietzche, F, On the Genealogy of Morals, reprinted Oxford Paperbacks Plant, Sadie, 1996, "On the Matrix: Cyberfeminism Simulations". Postman, Neil, 1985, Amusing Ourselves to Death, Methuen; (paperback 1987) Ryan, K, Click on Me: Identity as Commodity in the Digital Agehttp://www.newschool.edu/mediastudies/conf/pdf/kelly_ryan.pdf Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 1817, Biographia Literaria, Cited By Ferri, Anthony J. (2007) Willing Suspension of Disbelief: Poetic Faith in Film Sontag, S, 1977, On Photography, paperback reprint by Penguin, (1979) Steiner, R, 2003 Cast of Characters, Cindy Sherman Catalogue, Serpentine Gallery Stryker, S & Burke, P.J. (Dec., 2000), The Past, Present, and Future of an Identity Theory, Social Psychology Quarterly, Vol. 63, No. 4, Special Millennium Issue on the State of Sociological Social Psychology. pp. 284-297. Suler, J – Online Essays - http://users.rider.edu/~suler/psycyber/ Sullivan, James, quoted on http://www.cgw.com Turkle, Sherry. 1997.Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York:Touchstone, Watkins, Tony, 2001, Blurring Boundaries, http://www.damaris.org quoting Llinas, Dr. R, 2000, Brain Story, BBC TV 27