Uncertainty, Commitment and Exchange: The Emergence of Trust

advertisement

November 20, 2002

DRAFT

Commitment and Exchange: The Emergence of Trust Networks under

Uncertainty

By Karen S. Cook, Stanford University, Eric R.W. Rice, U.C.L.A., and Alexandra

Gerbasi, Stanford University

Introduction

When uncertainty and risk are associated with economic and social transactions

relatively closed trust networks often emerge to facilitate various types of informal

cooperation. In Russia, for example, “blat” was an extensive form of informal exchange that

emerged to provide scarce resources and services or favors (Ledeneva, Lomnitz etc.). Similar

exchange systems have been documented in a number of different contexts. Moving from a

social system in which the dominant mode of interaction is closed groups or networks to

more open networks such as those required to support the transition to a market economy and

democratic institutions may be difficult for a number of reasons. We draw on research on

exchange networks to explore some of these reasons. Our main claims are that uncertainty

and risk (such as that created by corruption and dishonesty) lead to commitment and the

formation of trust networks that tend toward closure. One disadvantage of such closed

networks of exchange is that they tend to limit access to opportunities outside the network.

Those in power in networks of exchange are less likely to form commitments and have more

reason to break out of these networks when they incur opportunity costs. Power asymmetries

impede commitment and under some circumstances reduce trust. Reputation systems and

1

third-party mediators (or guarantors) emerge under certain conditions to facilitate the move

from closed trust networks, often involving only family members and close associates, to

more open networks such as those required for the operation of market economies (see

Radaev, 2002, on the move from affect - based trust to reputation - based trust networks)

involving transactions with strangers. We draw on research (primarily experimental) on

exchange networks to offer insights into these network processes. We include discussion of

various examples of these processes based on evidence from survey and field research in a

wide variety of contexts, especially Eastern Europe.

Uncertainty, Trust and Forms of Exchange

Under conditions of uncertainty, trust networks are created to provide a more secure

transaction environment, especially when there is no reliable contract law or enforcement or

when the issues in exchange cannot be well handled with explicit contracts. The uncertainty

can arise from a number of sources and lead to different types of network solutions. Under

high uncertainty and high risk, transactions are likely to occur primarily among parties who

know each other well and form relatively closed associations or groups (e.g. families or

informal membership associations), in which the group boundaries are clear and membership

is easily determined (e.g. it is easy to detect who is in and who is out of the group). Insiders

are included in trades and outsiders are excluded. Optimum conditions of trade rarely exist

under these conditions. Corruption and a high potential for exploitation in the larger society

may lead to such closed-association systems of trade. As will be argued below, a major

difficulty with a quasi-closed system of trade is that it restricts the market for both “buyers”

and “sellers.”

2

Under lower threat of exploitation and levels of corruption closed-association trade

may give way to the formation of rudimentary reputation systems that enable individuals to

trade across membership boundaries and to establish indirect network ties to facilitate a

broader range of exchanges. These systems may emerge as transitional phases in the move

toward more open networks of exchange. We examine the emergence of trust networks under

varying conditions, but first we review the research on commitment between exchange

partners under uncertainty and the emergence of trust networks.

Within exchange theory (see Molm and Cook, 1995) a variety of types of exchange

have been investigated. The most common form of exchange is dyadic, restricted exchange in

which two parties engage in the exchange of valued goods or services for mutual benefit (see

also Ekeh 1974 and Blau 1964). The term “restricted” refers to the fact that the exchange is

isolated to the dyad. Emerson (1972) expanded the work on restricted exchange to focus on

the linkages between connected sets of exchange relations. Two exchange relations for

Emerson were viewed as connected to the extent that exchange in one relation affected the

frequency or level of exchange in the other relation. Two exchange relations A:B and B:C are

positively connected at B in an A-B-C network if exchange in one relation increases the

probability or frequency of exchange in the other relation. The connection is negative if

exchange in one relation decreases the frequency or probability of exchange in the other

relation. (Logically, the third category is a null relation, which is equivalent to no connection.

In Emerson’s work null relations are not important since they imply that the relations are not

connected and thus do not form a network link). Connected exchange relations form networks

of exchange, which may include different types of connections (i.e. mixed networks include

both positive and negative connections).

3

Dyadic exchange can be either negotiated or non-negotiated (see Molm and Cook,

1995). For Molm non-negotiated exchange involves the reciprocal giving of goods or

services in the hope that reciprocity will apply and the recipient will return the favor. (See

also Blau on the distinction between social and economic exchange). A different version of

reciprocal exchange is generalized exchange in which the reciprocity is generalized and not

particularized (i.e. between two connected actors). In generalized exchange goods or services

are transferred to one party in the hope that some other party may reciprocate, but the one

who reciprocates is not the person who is the direct recipient of the goods or services

(Takahashi 2000, Takahashi and Yamagishi 1999). A standard example in anthropology is

the Kula Ring (Malinowski).

Recent research by Molm, Takahashi and Peterson (2000) reports findings

differentiating two forms of exchange: negotiated and reciprocal dyadic exchange. Classical

exchange theorists (such as Blau 1964) proposed that trust is more likely to develop between

partners when exchange occurs without explicit negotiations or binding agreements (cf.

Macauly 1963). Under uncertainty and risk, exchange partners have greater opportunity to

demonstrate their trustworthiness by acts of reciprocal giving in the absence of negotiated

agreements. Molm et.al. (2000: 1398) demonstrate that reciprocal exchanges produce higher

levels of trust and stronger feelings of affective attachment and/or commitment than do

negotiated exchanges. The initial act of giving in a reciprocal exchange acts as a “signal” of

the actor’s trustworthiness to the recipient and creates the foundation for reciprocity of

exchange and eventually trust. The behavioral commitments that form also reduce the

inequality in the exchange and affect is, to some extent, dependent upon this reduction in

inequality as well as the signaling of trustworthiness. In an interesting paradox Molm claims

4

that these findings indicate that the mechanisms that were created to reduce risk in

transactions (negotiations and strictly binding agreements) have the “unintended consequence

of reducing trust in the relationship” since trust is not required if the agreements are binding.

This conclusion, however, is based on the fact that in an experimental setting the

experimenter serves as the “contract enforcer” and subjects are not allowed to renege on their

commitments. (For an experimental study in which this is not the case see Rice 2002,

discussed below.)

Under environmental uncertainty and conditions of high potential risk (as could be

created by corruption and widespread dishonesty) it can be argued that exchange systems are

more likely to be set up as negotiated exchanges than as reciprocal exchanges which require

more confidence and trust. In some ways, Molm’s findings regarding differences in perceived

trustworthiness of one’s partners under negotiated and reciprocal exchange regimes, suggest a

“Catch 22” exists. Molm, Takashi and Peterson report that one’s most frequent exchange

partner is rated as trustworthier under reciprocal exchange than under negotiated exchange.

The investigators reason that reciprocal exchange creates more uncertainty (since it is not

negotiated) and thus when it is successful and one’s initial “gift” of a service or valuable

resource (to initiate an exchange) is reciprocated, then a more reliable signal has been offered

that one is a trustworthy partner. Negotiated exchange does not provide an opportunity for

such a signal (unless the exchange can be reneged on as in Rice’s {2002} experimental

condition, referred to below as the “non-binding” exchange condition).

Commitment to Exchange Relations: Causes and Consequences

5

Commitment tends to occur more readily among power equals than among power

unequals in exchange networks (Cook and Emerson 1978). This fact has been supported by

recent research indicating that positive and frequent exchange among power equals creates

commitment and positive emotions toward the exchange relation (see Lawler and Yoon,

1998). The focus of most of the recent research within social exchange theory on the concept

of commitment, however, has linked commitment to social uncertainty. Cook and Emerson

(1984) define the degree of uncertainty as “the subjective probability of concluding a

satisfactory transaction with any partner” (Cook and Emerson 1984: 13). They found that

greater uncertainty led to higher levels of commitment with particular exchange partners

within an exchange opportunity structure. Commitment between exchange partners reduces

the uncertainty of finding a partner for trade and insures a higher frequency of exchange.

Commitment as defined by Cook and Emerson (1978) is behavioral. It refers to the decision

to continue to exchange with a particular partner (or set of partners in larger networks) to the

exclusion of alternatives that might be more profitable. Behavioral commitment in an

exchange opportunity structure creates relatively enduring exchange relations (rather than

spot markets). While affective commitment might emerge as a result of such ongoing

exchange it is treated as a separate factor to be explained. In this paper we use the term

commitment to imply behavioral commitment (not affective commitment). Behavioral

commitment implies an ongoing exchange relation that typically provides information about

the relative trustworthiness of the partners to the exchange. High levels of trustworthiness are

assumed to facilitate the emergence of a trust relation. Trust networks are connected

exchange relations formed in this manner. While commitment is expected to emerge under

6

conditions of uncertainty to provide the security for exchange in the future, such networks of

exchange are most likely to become trust networks under conditions of risk.

Recently research within exchange theory has conceptualized social uncertainty as the

probability of suffering from acts of opportunism imposed by one’s exchange partners

(Kollock 1994; Rice 2002; Yamagishi et al. 1998). Opportunism creates a different source of

uncertainty than the concern over the location of an exchange partner, the primary source of

uncertainty in Cook and Emerson (1978), involving the risk of exploitation. (Exploitation is

hard to block in networks of exchange unless the networks become closed and those who

cheat can be excluded from further interactions with those in the network). Social

uncertainty, created by the risk of exploitation, has also been shown to promote commitment.

Kollock (1994), Rice (2002) and Yamagishi et al. (1998) examined behavioral commitments

in environments that allow actors to cheat one another in their exchanges. Securing

commitments to specific relations is often the most viable solution to the problem of

uncertainty in these environments. If actors within a given opportunity structure prove

themselves to be trustworthy exchange partners, continued exchange with those partners

provides a safe haven from opportunistic exchangers. Such commitments, however, have the

drawback of incurring sizable opportunity costs in the form of exchange opportunities

foregone in favor of the relative safety of committed relations (Yamagishi and Yamagishi,

1994). This is one of the main dilemmas facing individuals in settings in which untrustworthy

behavior is common or where opportunism and corruption of some sort is the norm. And if

the equilibrium in the society is relatively closed trust networks, it may be difficult to break

out of this pattern of exchange to generate a more open network of exchange among relative

strangers. These trust networks among close kin or ethnic group members may actually serve

7

to reduce trust in outsiders or make it difficult to create since transactions occur rarely across

group boundaries (Rose-Ackerman 2000:536). (Later we discuss the possible effects of

reputation systems for this transition from closed to more open networks of trade and mutual

benefit.)

In Kollock’s (1994) initial study connecting opportunistic uncertainty and

commitment, actors exchanged in two different environments. In one environment (low

uncertainty) the true value of the goods being exchanged was known, while in the other (high

uncertainty) environment the true value of goods was withheld until the end of the

negotiations. He found that actors had a greater tendency to form commitments in the higher

uncertainty environment. Moreover, actors were willing to forgo potentially more profitable

exchanges with untested partners in favor of continuing to transact with known partners who

have demonstrated their trustworthiness in previous transactions (i.e. they did not

misrepresent the value of their goods).

Yamagishi, Cook and Watabe (1998) further explored the connections between

uncertainty and commitment, deviating from Kollock’s experimental design but coming to

similar conclusions. In their experiment, actors are faced with the decision of remaining with

a given partner or entering a pool of unknown potential partners. They employed several

modifications of this basic design, but in each instance the expected value of exchange

outside the existing relation was higher than the returns from the current relation. They found

that actors were willing to incur sizeable opportunity costs to reduce the risks associated with

opportunism. Moreover, they found that uncertainty in either the form of an uncertain

probability of loss or an unknown size of loss was able to promote commitments between

exchange partners.

8

In both the Kollock (1994) and Yamagishi et al. (1998) studies, exchange occurs

among actors in environments that allow for the potential for opportunism, but in which

actors are guaranteed finding an exchange partner on every round. In Rice’s (2002)

experiment actors exchange in two different environments: one that allows actors to renege

on their negotiated exchange rates (high uncertainty) and one where negotiations are binding

(low uncertainty). Exchange, however, also occurs within two network structures that vary in

degree of power inequality - a complete network in which all actors can always find a

transaction partner, and a T-shaped network, where one actor connecting three others at the

center has greater access to alternatives for trade than those on the periphery on the network.

Uncertainty promoted commitment in the complete network (power-balanced), but not in the

T-shaped network (a monopoly structure with maximum power inequality). Commitments,

he argued, are more viable solutions to uncertainty in networks in which power differences

are minimal. In networks that include a large power difference among the actors, the

structural pull away from commitment to explore alternatives is sufficiently intense as to

undermine the propensity to form commitments. Power is determined in such structures by

access to alternatives. Giving up alternatives reduces power.

Whereas Kollock and Yamagishi and his collaborators suggested that actors would

incur opportunity costs to avoid potentially opportunistic partners, Rice (2002) suggests that

such tendencies can be muted by power inequality in the network structure. This finding is

consistent with a number of studies in which the effects of power inequalities on the

formation of commitments have been investigated (see also Cook and Emerson, 1978, 1984;

Lawler and Yoon, 1996; Molm, Takahasi and Petersen, 2000). It is generally the case that

behavioral commitment is inversely related to the level of the power inequality in the

9

network. Thus, commitment is higher among power equals than among power unequals, all

other things being equal. Commitment is more common in horizontal than in vertical

relationships.

Rice (2002) explores other effects of commitment in exchange networks. In particular

he investigates how commitment affects the distribution of resources across relations and

within networks as a whole. He argues that commitments, when they occur, will reduce the

use of power in unequal power networks, resulting in a more egalitarian distribution of

resources across positions in a network. In networks where power between actors is unequal,

power-advantaged actors have relatively better opportunities for exchange than their powerdisadvantaged partners. These superior alternatives are the basis of power-advantaged actor’s

power. If, as uncertainty increases, power-advantaged actors form commitments with powerdisadvantaged actors, they erode the very base of their power. Forming commitments entails

ignoring potential opportunities. Alternative relations are the basis of structural power and as

these relations atrophy, the use of power and the unequal distribution of resources will be

reduced. For this reason increasing power inequality tends to lower the propensity for

commitment even under uncertainty. With increased risk of loss, however, even poweradvantaged actors seek committed partners for exchange.

Research results on exchange under social uncertainty thus indicate a strong tendency

for actors to incur opportunity costs by forming commitments to achieve the relative safety or

certainty of ongoing exchange with proven trustworthy partners (Kollock 1994; Rice 2002;

Yamagishi et al 1998). In addition to these opportunity costs, Rice (2002) argues that

commitments may also have unintended negative consequences at the macro level of

exchange. Actors tend to invest less heavily in their exchange relations under higher levels of

10

uncertainty. Moreover, acts of defection in exchange, while producing individual gain, result

in a collective loss, an outcome common in prisoner’s dilemma games. Both processes

reduce the overall collective gains to exchange in the network as a whole. So while there is a

socially positive aspect to uncertainty, in so far as commitments may increase feelings of

solidarity (e.g. Lawler and Yoon 1998) and resources are exchanged more equally across

relations (Rice 2002), there is the attendant drawback of reduced aggregate levels of

exchange productivity and efficiency.

As Powell and Smith-Doerr (1994:392) put it, “ties that bind may also turn into ties

that blind. When repeat trading becomes extensive it can turn inward, leading to parochialism

or inertia.” Marsden (1983) points out that networks may restrict access, in part through

brokerage arrangements and in part because they structure the flow of goods, resources, and

information, sometimes in less than optimal ways. Two examples provided by Powell and

Smith-Doerr (1994:392) of the potential negative effects of network arrangements involving

repeat trading include Powell’s (1985) study in which the “ossification of an editor’s

networks” is defined as the major factor in the decline of the list of products available from

the publishing house. The second example they provide is of the embeddedness of an

industry locked into a particular production network that created inertia and made the Swiss

watch making industry vulnerable and not responsive to the digital technology revolution

(Glasmeier 1991, as cited in Powell and Smith-Doerr 1994).

In another example provided by Henry Farrell, in the Italian packaging tool industry,

concentration in the industry has limited the contact between suppliers and end-producers in

ways that are counterproductive. Concentration limits the alternatives for the suppliers and

they become vulnerable to exploitation by the end-producers. A committed relation forms

11

between one particular supplier and end-producer further constraining the market and placing

the financial security of the supplier under the control of one specific end-producer. In a

contrasting case study of French machine producers, Farrell indicates how long-term

commitments are avoided as the end-producers strive to keep suppliers from depending too

heavily on them. Essentially the French producers, though powerful in the network, refrain

from long-term commitments and maintain the conditions that support market competition

for access to suppliers and, hence, responsiveness to changing economic factors.

Commitments can also have unintended consequences. As Mizruchi and Stearns

(2001) discover in their analysis of the use of social networks to complete deal between

commercial bankers and their corporate customers. They hypothesize that high uncertainty

leads the bankers to rely on colleagues with whom they have strong ties for advice and for

support of their deals. Their findings reveal that the tendency of bankers to rely on their

approval networks and on those they trust actually lead them to be less successful in closing

deals. This lower success rate in closing deals is viewed as the unintended consequence of

“purposive action” by Mizruchi and Stearns. Uncertainty, they argue (2001:667), creates

“conditions that trigger a desire for the familiar, and bankers respond to this by turning to

those with whom they are close.” The bankers in high risk environments turn to those they

trust even when seeking advice from a broader range of contacts (perhaps less trusted) might

make them more successful in the long run (especially with complex deals).

Under some conditions, then, networks can constrain the ability of the actors involved

to adapt to rapid economic or environmental change. These conditions have not yet been

spelled out in any systematic way, however. Our paper is an exploration of some of these

12

conditions in environments that are in flux, politically, socially and environmentally

including the dramatic cases of economic transition in Eastern Europe and elsewhere.

Commitment and the Formation of Trust Networks under Uncertainty

Exchanges are often “embedded” in networks of ongoing social relations. Uzzi

(1996) argues that “embeddedness” has profound behavioral consequences, affecting the

shape of exchange relations and the success of economic ventures. “A key behavioral

consequence of embeddedness is that it becomes separate from the narrow economic goals

that originally constituted the exchange and generates outcomes that are independent of the

narrow economic interest of the relationship” (Uzzi 1996: p.681). In related research Lawler

and Yoon (1996; 1998) and Lawler, Yoon and Thye (2000) argue that as exchange relations

emerge actors develop feelings of relational cohesion directed toward the ongoing exchange

relation. These feelings of cohesion result in a wide variety of behaviors which extend

beyond the “economic” interests of the relationship, such as gift-giving, forming new joint

ventures across old ties, and remaining in a relationship despite the presence of new,

potentially more profitable partnerships. While these are clearly positive aspects of these

commitment relations, there is also a downside when these relations become “locked-in” and

limit the range of exchange relations or the exploration of new opportunities.

A number of studies have begun to document the relationship between uncertainty

and the emergence of trust-based networks. Guseva and Rona-Tas (2001) compare the credit

card markets of post-Soviet Russia and the United States. They are concerned with how

credit lenders in each country manage the uncertainties of lending. In the United States, they

argue, credit lending is a highly rationalized process that converts the uncertainty of

13

defaulting debtors to manageable risk. Lenders take advantage of highly routinized systems

of scoring potential debtors, through the use of credit histories and other easily accessed

personal information. This system allows creditors in the United States to be open to any

individuals who meet these impersonal criteria.

In Russia, creditors must reduce uncertainties through personal ties and commitments.

Defaulting is an enormous problem in Russia, aggravated by the fact that credit information

such as that used by American lenders has, until quite recently, been unavailable. To

overcome these uncertainties Russian banks seeking to establish credit card markets must use

and stretch existing personal ties. Loan officers make idiosyncratic decisions about potential

debtors, based largely on connections to the bank, or known customers of the bank. In this

way defaulting debtors cannot easily disappear, as they can be tracked through these ties.

Viewed through the lens of recent theorizing on the connections between uncertainty and

commitments, these different strategies seem quite reasonable. As discussed earlier,

exchange theorists have repeatedly shown that as uncertainty increases, commitment to

specific relations likewise increases (Kollock 1994; Yamagishi et al. 1998; Cook and

Emerson 1984; Rice 2002). In the case of credit card markets, it is clear that the United

States presents an environment of relatively low uncertainty, compared to the high-levels of

uncertainty present in Russia. Exchange theory argues therefore that commitments will be

greater in Russia, which is exactly the case. Lending is facilitated by existing commitments

to the banks or the bank’s known customers. While such theoretical confluence is interesting,

it is in generating new insights that one can see the value of examining this situation through

the lens of exchange theory.

14

Rice (2002) argues that network structure will intervene in the process of commitment

formation. This insight suggests that sociologists ought to ask how different shaped networks

of potential debtors and lenders in Russia affect the use of commitments to procure credit?

Rice also argues that uncertainty, while promoting commitment, simultaneously reduces the

overall level of exchange in networks. This is another outcome observed in the Russian credit

card market, but one that is largely ignored by Guseva and Rona-Tas (2001). It is this aspect

of the problem that is addressed to some extent by Radaev (2002) on the emergence of

reputation systems in Russia. Finally, Yamagishi and his collaborators (Yamagishi et al.

1998) argue that uncertainty can stem from either the probability of loss or the size of loss.

Another question that should be raised in this context is how the size of loss, and not just the

potential for loss, relates to the behaviors observed in the Russian versus the American credit

card markets.

Exchange theory tends to focus on commitments as an outcome, not as a social

mechanism. In the case of the Russian credit card market, existing commitments provide a

mechanism through which network structures are expanded and changed. This raises the

issue of how interpersonal commitments may in turn create opportunities for network

expansion and/or reduction. Russian banks, for example, expand their trust networks by

issuing credit cards to families and friends of top bank executives (see also Ledeneva 1998).

As Guseva and Rona-Tas (2001:638) note: “Here the borrower-creditor relationship is

intermingled with close social bonds that serve as an additional guarantee and a channel of

information.” The social bond serves as a “bond” to reduce the risk of unrepaid credit.

Despite the fact that trust networks in which credit can be extended allow economic

transactions beyond direct exchanges, there is a limit to the extent to which such networks

15

will allow for movement to free trade. In fact, they may serve to hinder the development of

institutions that might serve as the basis for free trade (i.e. trade among strangers – what

Guseva and Rona-Tas view as the U.S. credit market).

Another way in which trust networks can be expanded to enlarge the number of those

in the market, according to Guseva and Rona-Tas, is to stretch the network by extending

credit to those indirectly tied to one another. “Trust is transitive,” they argue. But, because

this extends the risk involved, it is not used as a strategy beyond one-degree of separation. A

bank employee reveals the unwritten rule of credit extension: “there should not be more than

one person separating a bank official from an applicant” (Guseva and Rona-Tas 2001:639).

In the end person-to-person interviews are most often used in Russia to determine whether to

grant credit to an applicant. This requires the interviewer to develop the “art” of assessment

of the trustworthiness of the other. These security officers who grant or deny credit are

described by Guseva and Rona-Tas (2001:639) as lie detectors: “We have to stare the

applicants intently in the eyes, trying to guess whether they are telling the truth and whether

they should be issued a card.” The networks of trust in which the applicants are embedded are

used by the banks for security as well as for information should the applicant default. In the

U.S. this is done through the provision of the names of “credit references” on the application.

Applicants in the U.S. usually list a friend, co-worker or family member.

In his study of emerging markets for non-state businesses in Russia, Radaev (2002)

investigates the mechanisms and institutional arrangements that help actors cope with the

uncertainty and opportunism common in such an environment. Two features of the situation

are significant. Under uncertainty actors turn to interpersonal ties involving trust and greater

16

certainty to produce some security in the context of high levels of opportunism. This is the

behavior that is documented also by Guseva and Rona-Tas (2001) discussed above.

In documenting the uncertainty of business relations in Russia, Radaev (2002) surveys

indicated how important honesty and trustworthiness were in business partners. This result is

driven by the fact that there are frequent infringements of business contracts creating both

risk and high levels of uncertainty. Half of the respondents admitted that contract

infringements were quite frequent in Russian business in general and a third of the

respondents had had a high level of personal experience with such infringements. This degree

of opportunism creates barriers to the formation of reciprocal trust relations. There is

widespread distrust of newcomers to the market but established reliable partners are viewed

as more trustworthy.

In this climate commitment is clearly the most predictable response to uncertainty as

in the case of Kollock’s (1994) rubber markets and the credit card market discussed by

Guseva and Rona-Tas (2001). Another reason for the uncertainty is that the existing

institutions lack credibility and legitimacy. The courts do not effectively manage dispute

resolution and existing institutions do not secure business contracts. Banks can default, even

large ones assumed to be solvent. To cope with this fact the business community creates

closed business networks with reputation systems that define insiders and outsiders. This

system is based on information obtained from third parties, but more importantly on common

face-to-face meetings between potential partners.

In a completely different environment, McMillan and Woodruff (1999) find a similar

process in the transition from a planned economy to a market-based economy in Vietnam.

Here the market began as a result of small entrepreneurs using their ongoing relationships to

17

secure agreements. These social relations take the place of the non-existent contract law in

what remains of the planned economy. Cheating is easy in Vietnam because of the lack of

contract law and enforcement. According to McMillan, “What is striking about Vietnam is

that the entrepreneur’s incentive not to cheat a contract partner is not that the partner will sue

but that he’ll stop dealing altogether” (Quoted from Stanford Business 2000). Hardin (2002)

identifies this condition as the primary basis for trustworthiness. Since the courts can not be

trusted to resolve legal disputes (see also Montinola 2002) they create their own reputational

system promoted by gossip and meetings in teahouses where information is exchanged about

the credibility of various trading partners. “They try to avoid disputes by checking their

customers’ financial backgrounds and personalities with others who have done business with

them.” These informal exchanges, these investigators argue, create a business ethic that

supports a rudimentary market. Here we see the transition between closed trust networks and

the beginnings of a market economy through ties that are brokered in teahouses. Reputation

systems are essential in the formation of credit information that can be used to extend beyond

the reach of personal (and often closed) networks of exchange.

In a 1993 survey conducted by Radaev the emerging networks of entrepreneurs in

Russia primarily included personal acquaintances (42%), friends and their relatives (23%)

and relatives (17%). This fact reflects the reality in the credit card market in Russia (Guseva

and Rona-Tas 2001). Only a small percentage (11%) of the business contacts in 1993 were

new or relatively new acquaintances. More recently, however, there is a move away from

affect-based relations and trust to reputation-based trust as the networks formed purely on the

basis of acquaintance, kin ties, or friendship have tended to fall apart due to their inefficiency.

The relatively closed business networks that have emerged to replace the older “familial” and

18

friendship ties provide better information about the trustworthiness of the partners and their

competence. Within exchange theory the formation of commitment under uncertainty and

trust networks (see Cook and Hardin 2001) in the face of uncertainty provide theoretical

support for the evidence provided by Radaev (2002) and others on the recent emergence of

business networks in Russia. This argument is also consistent with Rice’s (2002) argument

that commitments can have negative aggregate level consequences for productivity and

efficiency in exchange systems.

Research in the exchange theory tradition on topics such as trust, strategic action,

commitment and reputational networks all have potential applications in the analysis of the

emergence of exchange networks in countries with transitional economies as well as in other

types of economies as evidenced by the work of many economic sociologists (e.g. Uzzi,

Granovetter, etc.). Moving from closed groups to more open networks of trade mirrors some

of the processes identified by Emerson (1972) as important for study from an exchange

perspective contrasting group-level exchange systems (productive exchange in corporate

groups) with network-level exchange. In addition, the return to the study of the significant

differences between social processes (e.g. power, justice and commitment) involved in

different types of exchange - negotiated, reciprocal and generalized exchange (Molm 1988;

Molm1990; Molm 1994, etc.) - has the potential to provide new insights into a variety of

emergent forms of exchange under different circumstances. For example, under uncertainty

negotiated, binding exchange may be more likely to emerge before reciprocal (most often,

non-binding) exchange will flourish, in part because it involves greater degrees of

uncertainty. Reciprocal exchange, as Molm and her coauthors have documented, generally

19

requires more trust since the terms of exchange are not simultaneously negotiated and

opportunism is possible (Molm et al 1999; Molm et al 2000).

Internet Trade, Markets and Reputation Systems

Yamagishi (forthcoming) demonstrates that the role of reputation systems varies

depending upon whether the social system is closed or open. In closed communities

reputation systems can be effective because negative reputations force exclusion (see also

Cook and Hardin, 2001). In more open societies negative reputation systems are less effective

because they are limited in the extent to which they are transferred to all those in the network

(or social system). Information flows only across those actors that are linked directly or

indirectly. In addition, actors can alter their identities in ways that make it easier to reenter

trade networks without being recognized as having had a negative reputation. The focus of

Yamagishi’s experimental study is an Internet trading network in which both the level of

honesty in the trades and the price can be tracked. Positive - reputation systems are more

effective than negative - reputation systems in the open networks. Actors are rated on their

honesty and thus accumulate reputation points that are published in the network during each

transaction.

Reputation systems are investigated by Yamagishi (2002, unpublished) as solutions to

the “lemons” problem in Internet markets, that is, the tendency for the goods on the market to

be low quality especially when there is asymmetric information. Typically, the lemons

market (Akerloff) emerges when the buyers have much less valid or reliable information

about the quality of the goods on the market than do the sellers (as is often the case in the

used car market). Buyers must rely on the reputation of the sellers to determine how much

20

confidence they have in the seller (i.e. how trustworthy the seller is). In this world of trade

Yamagishi demonstrates that the lemons problem is exacerbated when actors can change their

identities and reenter the market with a new identity (thus canceling their negative

reputation). They also demonstrate that positive reputations affect behavior differently since

actors develop an investment in their reputations and want to protect them. They lose this

positive reputation and their investment in it if they alter their identities. “The negative

reputation system that is designed to illuminate dishonest traders is particularly vulnerable to

identity changes, whereas the positive reputation system designed to illuminate honest traders

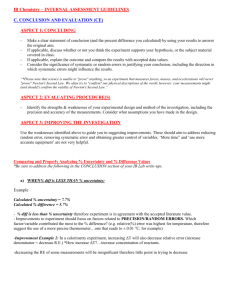

is not so vulnerable to identity changes”. The results concerning the quality of goods

produced under the different reputation systems (with and without the possibility of changing

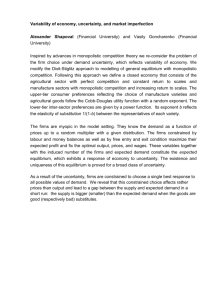

identities in the exchange network) are presented in Figure 1 below from Yamagishi

(forthcoming). The findings replicate those for the “lemons” market in terms of the low

quality of the goods (Experiment 1 – Control Condition) on the market without reputations,

but clearly demonstrate the superior role of positive reputations systems when identities can

be easily changes as would be the case in Internet trading. (Compare the two conditions in

Experiment 3 – negative and positive reputation conditions.)

Figure 1 About Here

The negative reputation system, however, as Yamagishi suggests, may work only

under the condition that someone who develops a negative reputation can be excluded from

trade effectively by the group acting as a whole. This requires a closed network (see also

Greif for a discussion of the difference between closed associations and open trade networks

among the Maghribi). Cook and Hardin (2001) also suggest that norms of exclusion work

21

only in groups and are not effective in open networks. Norms of exclusion function to

eliminate those who have “cheated” from the system of trade (Hardin 1995, 2002, chapter 5).

Kollock (1999) views the auction houses that have been created for trade on the

Internet as a laboratory for the study of the management of risk when there is little or no

access to external enforcement mechanisms. He studies the emergence of endogenous

solutions to the problems of risky trade (in cases in which no guarantees, warranties, or other

third-party enforcement mechanisms exist). The reputation systems that emerge to manage

this risk are the primary focus of his work. Yamagishi explores the differences documented

by Kollock between negative and positive reputation systems. Kollock (1999: 111) notes that

“a particularly disturbing strategy for fraud…in a number of online markets is the person who

works hard at establishing a trustworthy reputation, and then sets up a whole series of

significant trades and defaults on all of them, disappearing into a new identity after the fact.”

In a quantitative study of auctions on eBay, Kollock (1999b) provides evidence that at least

for some high-value goods, the price buyers paid was positively and significantly affected by

the seller’s reputation.

In a simulation study of the effects of positive reputation systems (similar in character

to the positive reputations studied experimentally by Yamagishi (forthcoming), Whitmeyer

(2000:196) finds that the effects of different types of positive reputation systems depend to a

large extent on the proportion of cooperators (as opposed to non-cooperators) in the

population. He examines the effects of reputation systems on general confidence gains in the

society. If the proportion of non-cooperators is low, any type of positive reputation system

will work because the non-cooperators will be more easily detected, especially if it is hard to

get a positive reputation. (Whitmeyer varied the degree to which it was easy or hard to get a

22

positive reputation in his simulation.) If the proportion of non-cooperators is high, then a

tough reputation system will mean lost opportunities for cooperation because some potential

cooperators will not be detected.

Uncertainty and the Emergence of Trust Networks for Services

The focus of our argument above is that in the economic arena, especially during a

major economic or political transition; trust networks emerge as a result of commitment

formation between exchange partners under conditions of uncertainty. Uncertainty can result

from the general lack of institutional support (and backing) for contracts and for enforcement

of the terms of trade, but also from corruption or the potential for exploitation that goes

undetected or even unpunished. (Add reference to paper by Montinola on corruption in the

courts in the Philippines.)

Illegal forms of behavior also result in risk and uncertainty and can lead to the

formation of similar trust networks. This is the type of trust built up in closed associations

such as the Mafia (Gambetta 1992), which are highly exclusionary networks. In the Mafia the

network includes only those who are members of the association and strong norms exist that

determine the nature of the acceptable behavior as well as the rules of trade. Only insiders

can participate, outsiders are excluded from the perquisites of “membership.” Where

governments have failed or where general institutions are corrupt then alternative

organizations like the Mafia may take over the economic arena and subsequently make it

difficult to put into place general market mechanisms. In such a situation risk and uncertainty

for those outside the organization may remain high since it is in the interest of the Mafia to

23

mediate economic transactions through its “trust networks.” Creating mechanisms to break

down the control of the Mafia (as the case of Russia makes clear) may be very problematic.

In a less dramatic case, Carol Heimer (2001) studies the trust network that emerged

during the early sixties to help women who needed access to abortion services that were

illegal at the time. Before the 1973 U.S. Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion, a

Chicago-based feminist abortion service referred to as “Jane” provided help to about 11,000

women. The trust networks built by this informal organization also served to protect the

identities of the physicians who provided these services. The risk was high for both parties,

since the women’s health was at stake and the physicians’ license to practice (and much more

recently their lives) were at stake. Under such high stakes it is interesting to investigate trust

networks formed and were maintained. Two features of the situation were critical. First, the

clients were vulnerable. The services they needed could not be obtained on the open market

(or in appropriate organizations) since the service was not legal and normal information

channels did not provide information on the reputations of the medical providers. Second, it

was also in the interest of the practitioners to establish trust relations with the clients since the

stakes were high if they were caught performing illegal abortions. They faced threats to jobs

and reputations in addition to possible prison terms. Of course, the most important feature of

the network was to provide information not only on availability of the service, but also to

provide information on the quality of the service. In this way one could assume that

incompetent practitioners had been eliminated from the network (though this was clearly not

always the case since many women died as a result of receiving an abortion during this time

period). This reputational information was collected and provided as a critical service to those

who needed it by this third party organization, “Jane,” committed ideologically to women’s

24

rights in the area of fertility decisions. Later we discuss other third party forms of mediated

information relevant to trustworthiness and securing the possibility of engaging in

interactions with strangers especially those involving risk and uncertainty.

Under some circumstances trust networks emerge for the provision of a broad range

of services such as healthcare. These networks often fill the void left by institutions (or

simply fill the information void even when institutions work fairly well). In addition to

networks used to obtain care, side payments can be required to get high quality services in

certain situations. Hungary is an example (Kornai, 199x). Rose-Ackerman (2001), among

others, comments on the medical arena as an area in which corruption exists in some of the

post-socialist societies - along with university admissions in Poland and Slovakia and

customs officials in a number of countries (Miller, Grodeland, and Kosheckhkina 1999).

Rose-Ackerman examines general issues of trust and honesty in the post-socialist societies.

The kinds of benefits that are obtained from contacts and bribes, she suggests, is an important

topic for further research given that there are rather large differences across countries in the

perceived incidence of corruption. The system of side-payments for medical care, for

example, is maintained in some countries both by professionals who seek bribes and by

clients who pay them in order to obtain individualized benefits or better service. This leads

to what Rose-Ackerman (2001: 424) calls a “self-sustaining system of corruption.” People

pay the extra payments because others do. What they continue to do is based to a large extent

on what they think others are doing, in a common collective action problem. Public opinion,

Rose-Ackerman notes, is against corruption, but the system is maintained at the level of

individual behavior because individuals benefit from the system even though it may be

collectively irrational (even against collective opinion). Solving this problem will be difficult

25

since it requires that individual behavior be coordinated on a different solution entirely to the

problem of obtaining benefits.

Transitions from Closed to Open Networks: Possible Solutions and Limitations

While we have discussed factors that help explain the emergence of relatively closed

trust networks under uncertainty, a problem for transitional economies is to understand the

nature of the changes that occur when societies shift from one type of economy to another

(i.e. from a planned economy to a market economy). Relatively closed trade associations or

closed trust networks may create problems for the shift to a market economy that requires

open networks to facilitate trades among strangers. For example, consumer credit remains

limited in the Russian economy primarily because there is no good way to secure these

transactions until more general institutions are built up that can provide the kind of

“insurance” that will make transactions with strangers involving loans and extensive credit

possible. Without these institutions, or in the face of weak and unreliable institutions (not to

mention untrustworthy institutions) markets are limited by the reach of actors’ ties to one

another in the society, since trust networks can provide the security for trade that cannot be

offered by institutional safeguards. The social embeddedness of these more limited networks

for the distribution of goods and services serves to facilitate exchange, but restricts the

development of completely open markets of trade. Investment in particular social relations of

assurance (as Yamagishi argues) can work to the detriment of the development of

“generalized trust”. His comparisons between the U.S. and Japan, in this respect, are telling

(see also, Cook et. al. 2002, unpublished; and Yamagishi, Cook and Watabe, 1998).

26

For quite different reasons than in Eastern and Central Europe there are extensive

closed networks of trade in Japan, a society in which what has been called a more

“collectivist” culture exists. Generalized trust is lower in Japan than in the United States,

reflecting to some extent this cultural difference, but also a difference in the standard mode of

exchange. It is only relatively recently (in the past two decades) that credit was widely

available to Japanese citizens or that one could order a plane ticket, for example, through the

mail. Many of these transactions were required to be face-to-face. As in the Russian example

above, merchants and bankers viewed themselves as less likely to be exploited in a face-toface transaction. (Recall that in Russia Radaev reports that credit must be obtained through a

personal interview.) Also, because general trust was low in both cases, it was not considered

wise to use the mails to transfer valuable goods.

Lincoln, Gerlach and Takahashi (1992) indicate in their study of Japanese businesses

how important the “keiretsu criteria” of trust and long-term relationships are for business.

The keiretsu networks are both horizontal and vertical linkages between firms that were

believed to provide Japan an economic advantage during the Japanese economic miracle.

Keiretsu networks were fairly stable sets of regularized exchange relations that reduced the

market to a structured set of trading partnerships (Cook and Hardin 2001). To some extent

such networks reduce transaction costs and risk. As Scharpf (1994:27) puts it, “when such

ongoing relations do exist, the reliability of actors’ expectations, and their trust in each

other’s commitments, may be raised far above the level that would be reasonable even among

well-socialized strangers.” While such networks offer some advantages to limit competition

and provide security of trade under some economic conditions, the downside is that they can

constrain economic growth and restrict opportunity.

27

The use of personal ties for business purposes is also a strong tradition in China where

there are many overlapping networks involving different types of social relations. Kin-based

ties form the main avenue of entry into the economy for Chinese families. Reputation

systems exist in the form of “quanxi contacts” that provide assurance of trustworthiness when

a new deal is to be consummated. The quanxi contact is the intermediary or third party

guarantor. Because such quanxi relations are built up over time, however, and embody longterm commitments (some even transferred intergenerationally), they cannot be built up over

night. In addition, they are embedded in what Hamilton and Fei (1992) call “relational

codes”. Such codes clearly restrict entry into the marketplace.

Other factors can also limit entry into the economic marketplace for societies that do

not yet have a market economy. Brown (2003) describes the vanilla trade in Madagascar in

villages in which distrust prevails primarily among kin. Distrust is so pervasive that it invades

families since there are few non-kin available as trading partners. Closeness of relation does

not seem to modify the effect since even husbands and wives do not often trust each other.

Wives typically maintain the books and keep information from their husbands as a way of

limiting their extra-marital activities. In such an environment the eventual establishment of

trust networks with non-kin for trade would seem unlikely, given that kinship does not even

secure trustworthiness.

One key to the problem of trust and the transition from socialism identified by RoseAckerman (2002) is that there may be a contest between the existing trust networks (based on

what she terms reciprocal trust) that emerged as a coping mechanism under socialism and the

necessary “trust in rules” or confidence in new institutions that will act in a fair and impartial

manner. Personal links may undermine reform efforts, she concludes (2002:559). “Russians

28

and Central and Eastern Europeans established dense networks of informal connections to

cope with the difficulties of life under socialism and some of these practices have continued

as ways of coping with the present (Rose 1999:10; Ledeneva 1998). One question raised by

the transition is whether the legacy of these informal connections is helping or hindering the

process of institutionalizing democracy and the market.”

In an interesting comparison between Russia and Central and Eastern Europe, RoseAckerman (2002:565) reports that initial research indicates that in the Central European

economies more reliance is placed on the courts as arbiters in the case of contract failures.

This makes market deals among strangers possible at an acceptable level of risk. Reciprocal

trust can then emerge among initial strangers in repeat transactions. In contrast, where there is

less confidence in legal enforcement such as in Russia and in the Ukraine (where the courts

are viewed as corrupt and open to bribes) “economic actors are reluctant to deal with

outsiders.” In this case, as Rose-Ackerman points out, “both buyers and sellers are locked

into mutually reinforcing relationships that may limit disputes, but also limit competition and

entry.” The research question that is posed in this analysis is precisely when and under what

conditions does reciprocal trust among close kin and friends undermine or enhance the

establishment of “one-sided trust in the reliability of institutions.” It requires insiders to

interact with outsiders on the basis of standard norms of contractual obligations (ideally

backed by law) as if they were members of the same “group”. Whether this can be

accomplished is an important question and one that goes to the heart of the matter in many

countries undergoing a political/economic and major social transition.

The interesting paradox that has been revealed in some of the recent work on different

forms of exchange and their implications for commitment and trust under uncertainty (e.g.

29

Molm, etc.) is that the very procedures that are put in place to make transactions more

reliable and to increase confidence in the market may undermine the basis for trust. As Molm

concludes (2000:1425), when the shadow of the future is short and exploitation is profitable

then the risk inherent in reciprocal exchange may outweigh the benefits. In such situations

what she calls “assurance structures,” which are mechanisms for creating negotiations that

are binding and enforceable, may actually decrease trust - or at a minimum fail to provide the

conditions for building trust.

In contrast, Molm argues that reciprocal trust relations may have a positive benefit if

they lead to generalized trust relations. This is the central dilemma. They may lead to more

general trust or may simply reinforce trust for those within the network created by reciprocal

exchange relations. Molm claims (2000:1425) that “through numerous experiences with

specific others who behave in a trustworthy manner under conditions of risk, we may come to

expect that others, with whom we have no direct experience, will also be worthy of our trust.”

But this is an empirical question and in order to answer it we should vary the level of

uncertainty and risk involved in the situation. Only then could we draw inferences about

situations like those faced in transitional economies. While it is agreed that an environment in

which generalized trust is high (see Fukuyama, Yamagishi and Yamigishi, etc.) may result in

advantages - since individuals and firms are able to explore new relations and take advantage

of new opportunities in social, business, and political arenas - this depends centrally upon the

nature and level of the risks involved. Only under certain conditions is it likely that the kind

of particularized trust that emerges in trust networks will lead to trust of those outside one’s

direct experience (as well as indirect experience through reputations obtained from

trustworthy contacts within the network) or to assessments of the generalized trustworthiness

30

of strangers. This move is complex and may rely on the kinds of institutions that arise to

manage defaulting.

We have focused on uncertainty and its effects on the emergence of trust networks

and subsequently the transitions from trust networks to open networks of exchange that move

beyond direct personal bonds. We have not dealt explicitly with situations in which the level

of distrust is so high that it is difficult to imagine how one would get to real markets. As

Rose-Ackerman (1999:436) puts it, widespread distrust in institutions, as exists in Russia and

some of the Eastern European countries, leads to a focus on interpersonal distrust. The only

“counterweight here,” she claims, “is the creation of exclusive trusting networks operating

inside or outside the formal institutional framework.” In situations of high levels of distrust,

however, as we have indicated above, the move from these closed trust networks to open

networks of trade may be difficult.

The move to reputation systems may be one of the intermediate steps that might work

to extend the network. The information provided from the closed trust networks might then

be useful in providing reputations that are credible since it could include both positive

information about trustworthiness and negative information about defaulting behavior. This

step might foster the extension of trade beyond the bounds of direct personal ties. A potential

difficulty, however, is that if the distrust of outsiders is intense, the reputational system that

evolves may simply reinforce the divide between those in the trust network and those outside

of it, making any extension of trade across this divide difficult. This implies that beyond the

nature of the reputational system that develops (as Yamagishi argues), the degree of distrust

and its distribution across groups in the society is critical. An interesting aside here is that it

may be precisely in this kind of situation that Putnam’s panacea might work. Associations

31

that crosscut the major cleavages in the society, if they exist (perhaps in the form of sports

teams or other interest based clubs not derived from ethnic group identity), may serve to build

bridges across this divide.

Another key factor is the proportion of potential cooperators in the society and, as

Whitmeyer demonstrates, when that proportion is low any reputational system that helps us

locate the ones who are cooperative will be useful. Investigating the different paths from

closed associations to open networks of trade would be a useful research project in the

various countries now undergoing tremendous economic change. From Hungary and Poland

to South Africa and Vietnam, the study of uncertainty and the emergence of trust networks as

one possible path to open markets (or as a hindrance to the development of open markets) is

an important next step in our research agenda. It will also be important to study

experimentally the features of reputation systems or that may help make open network

trading feasible, especially in environments in which some cheating is likely to occur.

Third parties may be important intermediaries in the move from closed to open

networks for trade and other business transactions. As in the case of Vietnam, discussed

above, teahouses link individuals unknown to each through indirect ties and the transfer of

relevant information about trustworthiness. Or, as in the case of Russia, discussed by Radaev,

rudimentary credit associations are beginning to emerge that facilitate face-to-face meetings

in which reputations for trustworthiness can be transmitted in much the same way as in the

Vietnamese teahouses. These informal modes of cooperation may have the externality of

extending the credit available in segments of the society by providing information about the

trustworthiness of those that can be indirectly linked in networks that extend beyond the trust

networks that generally work on the basis of relatively direct ties.

32

Reputational systems are used to extend credit and make transactions possible that are

unlikely without credible information about trustworthiness. In much the same way that

rudimentary credit associations are emerging in Russia to “certify” customers as trustworthy,

professional associations often emerge to “certify” the competence and trustworthiness of

various professionals so that their clients or consumers (often unable to judge for themselves)

can be assured that they will be treated appropriately. These associations can do more than

certify, they may also regulate those who are members. They can sanction those who do not

live up to the reputation of the profession and even exclude from membership those who

violate the professional ethics or relevant codes of conduct. The full-fledged emergence of

credit associations backed eventually by fiduciary and contract law might take this form in

Russia and Eastern Europe. It would involve third party accreditation and confidence that the

information being provided was accurate. Whether any of these reputational mechanisms

work to “guarantee” trustworthiness and under what conditions they succeed in extending the

reach of trust networks to foster markets needs further empirical investigation. Without this

step in a climate of dishonesty and exploitation trust networks are likely to remain the

dominant mode of exchange. Restricted network exchange, in this context, is one mechanism

for avoiding the risk of entering and re-entering the “market for lemons.”

33

References

Axelrod, Robert. 1984. The Evolution of Cooperation. New York: Basic Books.

Blau, P.M. 1986. Exchange and Power in Social Life, 2nd printing. New Brunswick, NJ:

Transaction Books.

Bearman, Peter. 1997. "Generalized Exchange." American Journal of Sociology 102:13831415.

Brown, Margaret L. 2003. “Compensating for Distrust among Kin.” In R. Hardin (ed.)

Distrust. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Press.

Cook, Karen S., Emerson, Richard M. 1978. "Power, Equity and Commitment in Exchange

Networks." American Sociological Review 43:721-739.

Cook, Karen S., Emerson, Richard M. 1984. "Exchange Networks and the Analysis of

Complex Organizations." Research in the Sociology of Organizations 3:1-30.

Cook, Karen S., Richard Emerson, Mary R. Gillmore, and Toshio Yamagishi. 1983. "The

Distribution of Power in Exchange Networks: Theory and Experimental Results."

American Journal of Sociology 89:275-305.

Cook, Karen S., and Mary R. Gillmore. 1984. "Power, Dependence and Coalitions." Pp. 2758 in Advances in Group Processes, edited by Edward J. Lawler. Greenwich, CT: JAI

Press.

Cook, Karen S., and Russell Hardin. 2001. "Norms of Cooperativeness and Networks of

Trust." Pp. 327-347 in Social Norms, edited by M. Hechter and K-D. Opp. New York:

Russell Sage Foundation.

34

Cook, Karen S., and Toshio Yamagishi. 1992. "Power in Exchange Networks: A PowerDependence Formulation." Social Networks 14:245-265.

Ekeh, Peter. 1974. Social Exchange Theory: The Two Traditions. Cambridge: Harvard

University Press.

Emerson, Richard. 1962. "Power-Dependence Relations." American Sociological Review

27:31-41.

Emerson, Richard. 1972. "Exchange Theory Part I: A Psychological Basis for Social

Exchange." Pp. 38-57 in Sociological Theories in Progress, edited by Joseph Berger,

Morris Zelditch Jr., and B. Anderson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Emerson, Richard. 1972. "Exchange Theory, Part II: Exchange Relations and Networks." Pp.

58-87 in Sociological Theories in Progress, edited by Joseph Berger, Morris Zelditch

Jr., and B. Anderson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Farrell, Henry. (2003). “Trust, Distrust, and Power.” In R. Hardin (ed.), Distrust, New York:

Russell Sage Foundation Press.

Friedkin, Noah E. 1993. "An Expected Value Model of Social Exchange Outcomes." Pp.

163-193 in Advances in Group Processes, edited by Edward J. Lawler. Greenwich,

CT: JAI Press.

Guseva, Alya, and Akos Rona-Tas. 2001. "Uncertainty, Risk, and Trust: Russian and

American Credit Card Markets Compared." American Sociological Review 66:623646.

Hamilton, Gary, and Xiaotong Fei. 1992. From the Soil: The Foundation of Chinese Society.

Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

35

Heckathorn, Douglas D. 1984. "A Formal Theory of Social Exchange: Process and

Outcome." Current Perspectives in Social Theory 5:145-180.

Heckathorn, Douglas D. 1985. "Power and Trust in Social Exchange." Pp. 143-167 in

Advances in Group Processes, edited by Edward J. Lawler. Greenwich, CT: JAI

Press.

Heimer, Carol. 2001. Trust, Vulnerability and Uncertainty. Ppxx in K.S. Cook (ed.) Trust in

Society. New York City, New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Homans, G. C. 1974. Social Behavior and Its Elementary Forms. New York: Harcourt, Brace

and World.

Kollock, Peter. 1994. "The Emergence of Exchange Structures: An Experimental Study of

Uncertainty, Commitment, and Trust." American Journal of Sociology 100:313-45.

Kollock, Peter. 1999. “Trust in Online Communities.” In E Lawler (ed.) Advances in Group

Processes Vol. Xx (?)

Lawler, Edward J., and Jeongkoo Yoon. 1993. "Power and the Emergence of Commitment

Behavior in Negotiated Exchange." American Sociological Review 58:465-481.

Lawler, Edward J.; Yoon, Jeongkoo. 1996. "Commitment in Exchange Relations: Test of a

Theory of Relational Cohesion." American Sociological Review 61:89-108.

Lawler, Edward J.; Yoon, Jeongkoo. 1998. "Network Structure and Emotion in Exchange

Relations." American Sociological Review 63:871-894.

Lawler, Edward J., Jeongkoo Yoon, and Shane R. Thye. 2000. "Emotion and Group

Cohesion in Productive Exchange." American Journal of Sociology 106:616-657.

Leik, Robert K. 1992. "New Directions for Network Exchange Theory: Strategic

Manipulation of Network Linkages." Social Networks 14:309-323

36

Lincoln, James R., Michael Gerlach, and Peggy Takahashi. 1992. “Keiretsu Networks in the

Japanese Economy: A Dyad Analysis of Intercorporate Ties,” American Sociological

Review 57: 561-585.

Macy, Michael W, and John Skvoretz. 1998. "The Evolution of Trust and Cooperation

between Strangers: A Computational Model." American Sociological Review

63:638-660.

Markovsky, Barry, David Willer, and Travis Patton. 1988. "Power Relations in

Exchange Networks." American Sociological Review 5:101-117.

Markovsky, Barry, John Skvoretz, David Willer, Michael J. Lovaglia, and Jeffrey Erger.

1993. "The Seeds of Weak Power: An Extension of Network Exchange Theory."

American Sociological Review 58:197-209.

Mizruchi, Mark S. and Linda Brewster Stearns. 2001. “Getting Deals Done: The Use of

Social Networks in Bank Decision-Making.” American Sociological Review 66

(October): 47-671.

Molm, Linda. 1997. Coercive Power in Social Exchange. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press.

Molm, Linda. 1997. "Risk and Power Use: Constraints on the Use of Coercion in Exchange."

American Sociological Review 62:113-133.

Molm, Linda, and Karen S. Cook. 1995. "Social Exchange and Exchange Networks." Pp.

209-235 in Sociological Perspectives on Social Psychology, edited by Karen S. Cook,

Gary Alan Fine, and James S. House. Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Molm, Linda, Gretchen Peterson, and N. Takahashi. 1999. "Power in Negotiated and

Reciprocal Exchange." American Sociological Review 64:876-890.

37

Molm, Linda, Theron M. Quist, and Phillip A. Wiseley. 1994. "Imbalanced Structures, Unfair

Strategies: Power and Justice in Social Exchange." American Sociological Review

49:98-121.

Molm, Linda, N. Takahashi, and Gretchen Peterson. 2000. "Risk and trust in social exchange:

An experimental test of a classical proposition." American Journal of Sociology

105:1396-1427.

Montgomery, J. 1996. "The Structure of Social Exchange Networks: A Game-Theoretic

Reformulation of Blau's Model." Sociological Methodology 26:193-225.

Radaev, Vadim. 2002. "Entrepreneurial Strategies and the Structure of Transaction Costs in

Russian Business." Problems of Economic Transition 44:57-84.

Rice, Eric R.W. 2002. The Effect of Social Uncertainty in Networks of Social Exchange.

Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation.

Rose-Ackerman, Susan. 2001. “Trust and Honesty in Post-Socialist Societies.” Kyklos, Vol.

54: 415-444.

Takahashi, N. 2000. "The Emergence of Generalized Exchange." American Journal of

Sociology 105:1105-1134.

Takahashi, N., and Toshio Yamagishi. 1996. "Social Relational Foundations of Altruistic

Behavior." Japanese Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 36:1-11.

Takahashi, N., and Toshio Yamagishi. 1999. "Voluntary Formation of a Generalized

Exchange System: An Experimental Study of Discriminating Altruism." Japanese

Journal of Psychology 70:9-16.

38

Uzzi, Brian. 1996. "The Sources and Consequences of Embeddedness for the Economic

Performance of Organizations: The Network Effect." American Sociological Review

61:674--698.

Whitmeyer, Joseph. 2000. “Effects of Positive Reputation Systems” Social Science Research

29, 188-207.

Yamagishi, Toshio, Karen S. Cook, and M Watabe. 1998. "Uncertainty, Trust and

Commitment Formation in the United States and Japan." American Journal of

Sociology 104:165-194.

Yamagishi, Toshio and Midori Yamagishi. 1994. “Trust and Commitment in the United

States and Japan.” Motivation and Emotion Vol. 18 (2) 129-166.

Yamagishi, Toshio. 2002. “The Role of Reputation in Open and Closed Societies: An

Experimental Study of Internet Trade” (unpublished).

39

90

Expt 1,

Control

Expt 1, ID

Average Quality Level

80

70

Expt 1,

Reputation

Expt 2

60

50

40

Expt3,

Positive

Expt3,

Negative

30

20

10

0

1

2

3

4 5 6

Tim e Block

7

8

9

Figure 1: Reputation System Effects on Average Quality Level of Goods Exchanged in the

positive reputation condition and the negative reputation condition in Experiment 3,

compared to the levels in Experiments 1 and 2. (Yamagishi, forthcoming)

40