`Reflection` section from a PhD thesis (word doc)

advertisement

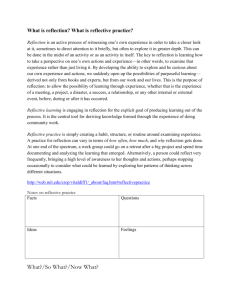

Taken From: Captivated by Learning, Morgan,L 2001: Section 3, Unpublished Thesis:Lancaster. Reflection as a data source: It was my intention that the way in which I interpreted and analysed all the interviews produced ‘communal narratives’ of articulated understanding of practice. Interviewing was not my only source of qualitative data of this reflective nature, I had also instigated a form of data collection which supplemented the interview material, and which I chose to call ‘reflective statements’. Participants in the programme, whether tutors or students, were invited to produce a written reflective statement. In the main these responses were produced by students completing a degree programme and in this sense they had a ‘therapeutic’ element to them. Many students, particularly those undertaking an MA course over 3 or 4 years with a research based dissertation as the final year had reported a feeling of ‘bereavement’ once the final work was handed in. Their personal lives had become so bound up with producing assignments, fitting writing and research around their homes, families and careers, and being almost physically attached to a computer, that the end of this process produced a chasm of empty space that once was filled with life, had temporarily been replaced by study, and was now vacant again. Wearing my ‘counselling’ hat, but in my ‘research officer role’ I had spent some time talking with such students, helping them to consider what might fill the gap created by completing a dissertation and generally providing a professional sounding board for the new educational ideas, and ‘professional learning plans’ (Knight and Trowler 2001) that had been evoked by their research. As our numbers increased, this aspect of my work, whilst still important, became difficult to protect in terms of time. I conceived the idea of using a written format for students to reflect on the programme, perhaps considering where it would lead them to, what it had been like, the highs and lows of the experience. They accepted that this material might be used in my research. I gave them no required length, no desired format, I was interested in their own personal thoughts, and we discussed how this might have a therapeutic effect, such as occurs when you write in a journal. Grumet (1989) cited in Moon (2000:187) suggests that writing ‘ imposes form on experience’. Jennifer Moon argues that ‘journal writing also provides a means by which learning can be up-graded – where unconnected areas of meaning cohere and a deeper meaning emerges’. These processes, she suggests ‘can be directed towards a wide range of outcomes or purposes in improvement of the learning experience itself.’ The reflective statements were not unlike journal entries, the respondents used ‘comfortable, ready to hand language’ for ‘situations which were new, puzzling, troubling or intriguing’ (Parker and Goodkin 1987:14). Abbi Sax speaking on Radio 4 in December of 2000 (about his period in solitary confinement in South Africa), suggested that ‘writing is the way that I order the chaos of my thoughts.’ This idea certainly can be traced in the responses that I gained in this method of data collection. Respondents all stated that the exercise had helped them and had enabled them to rationalise their feelings about the experience and reflect more deeply on its value to them in their work and in their 79 lives. Many reported being ‘changed’ by the experience. The responses were of varying length, some very sophisticated, some very exploratory, some clearly heartfelt outpourings of feelings. Research journal: My own reflections on my post and the development of the Centre as it progressed were recorded in a professional journal. Parker and Goodkin (1987:14) identify the informal language of a personal professional journal as the way in which the writer can deal with situations which are ‘new, puzzling, troubling or intriguing.’ This form of personal writing, Moon (1999:30) suggests allows us to ‘get into a relationship with an issue.’ In the early stages of my appointment and the development of the Centre (the ‘Enterprise’ of the Case Study), my journal was used to test ideas and theories of practice, to evaluate mine and others module teaching, to discuss issues arising from confrontation with bureaucracy, HE and LEA procedure and supervision confidentiality. The role was very complex and very demanding of my personal endurance resources, the journal became a way to off-load issues that needed to mature before being dealt with, particularly those of an ‘ethical, moral or sociopolitical context’(p.33). Moon (ibid:187) argues for the journal’s place as ‘a means by which learning can be up-graded – where unconnected areas of meaning cohere and a deeper meaning emerges.’ Grumet, (1989 in Moon 1999) summarises this very neatly: ‘It imposes form on experience.’ My own journal was used as a data source, the contextualizing of sequential events, and a way of monitoring the development of my personal praxis. The interpretation of reflection: Reflection as a ‘theory-in-practice’ has been so fully explored both by its chief proponent Donald Schön, (1983,1987) and by numerous distinguished writers on experiential and transformative adult learning; notably, John Dewey (1938), David Kolb (1984), Jack Mezirow (1981,1991), Michael Eraut (1994) et al., that it needs no further reiteration of its value as a learning technique, here. However both Mezirow (1981,1991) and Eraut (1994) have called into question the validity of such a broad brush as ‘reflection-in-action’ and ‘reflection-on-action’. What do these phrases mean, and are the tacit implications therein available for analysis? My intention was to look at the way that practitioners articulated their own learning – this would inevitably be a form of reflection, in order to interpret their deeper meanings and pursue an analysis of this ‘reflection’ I felt that I needed some form of sub-division or deconstruction for the term. Initially I thought that the model produced by Mezirow (1981:12-13) in which he distils six conditions of reflection (listed below) would enable me to put a deeper interpretation on the statements of my respondents, whether in interview or in a written form. It would I hoped also enable me to consider my own reciprocal reflection during the course of the interview. During further study I came across the work of Susan Hart (1995) in which she uses a process of observation analysis which she terms interpretive modes to understand and reflect on the actors (teachers) understanding of the action within a classroom in which she is a non-participant observer, but is a teacher. I decided to test both of these forms of interpretation. In a pilot study (Morgan, 2000 Theoretical Reflectivity (Module B 3.2) I took a sample transcript and used Mezirow’s conditions and Hart’s modes, to interpret what was happening within the conversation. It was complex as an exercise, because the 80 terminology did not sit easily with the type of conversation in which the participants and I were involved, the situated nature of the discussion needed more specific descriptors. However I did feel that a deconstruction of the term ‘reflection’ was important in order to examine all the types of reflection that were coming from this dialogic procedure, and to relate these ideas to ‘knowing’ in Blackler’s (1995) sense, and ‘sensemaking’ according to Weick (1995) within organizations, and within the ‘communities of practice’ in which I and my respondents worked. I decided that I should think about reflection in terms of its meaning-in-context. By synthesising the work of Hart and Mezirow, looking at how they had created meaningful terms and then creating a suitably ‘situated’ terminology together with explanatory examples of use. I constructed new labels and a rationale (the rationale is explored further in interlude 4) to offer me a way to interpret and integrate the interview and the reflective statement data for analysis. This was done in relation to an understanding of the knowledge of communities, and the personal situatedness of that knowing within professional practice. (Reflective data tools – Appendix C) In the deconstruction which follows, both Mezirow’s (1981) and Hart’s (1995) full terminology are shown first, followed by my own version of the deconstruction of reflection for the interpretive analysis of qualitative material. Mezirow (1981:12-13) suggests seven different conditions of reflection, the final one of these he argues, is crucial for perspective transformation: affective reflectivity: awareness of how the individual feels about what is being perceived, thought or acted upon; discriminant reflectivity: assessing the efficacy of perception, etc. judgmental reflectivity: making and becoming aware of the value of judgements made; conceptual reflectivity: assessing the extent to which the concepts employed are adequate for the judgement; psychic reflectivity: recognition of the habit of making percipient judgements on the basis of limited information; theoretical reflectivity: awareness of why one set of perspectives is more or less adequate to explain personal experience. Whilst these offer types or conditions of reflection they do not offer a language for how they might be observed to occur. Susan Hart (1995:224) discussing the way that a persons actions and perceptions might be interpreted during observation suggests the following modes of interpretation of action and perception: Interconnective Mode: explores possible links between the person and the learning context, asking. ‘What in this situation might be helping to produce this response?’ Oppositional Mode: challenges interpretations previously made by offering alternative interpretations of the same evidence, asking. ‘How else might this response be understood?’ It seeks to uncover the norms and assumptions underlying a judgement, so that these can be reviewed and evaluated. Decentred Mode: encourages challenge to the interpretation of the ‘teachers’ frame of reference by inviting an appreciation of how the activity might affect the ‘student’. What meaning and purpose does this activity have for the ‘student?’ 81 Affective Mode: examines the part that feelings are playing in a situation, and in leading us to arrive at that particular interpretation. ‘How do I feel about this?’ and ‘What do these feelings tell me about what is going on here?’ Hypothetical Mode: asks whether there might be a need to suspend judgement for the time being in order to learn more. ‘What else do I need to do/learn in order to be able to reach an adequate understanding of this persons learning?’ In considering what sort of reflection practitioners might engage in when discussing their perceptions of their own experience and articulating the conditions of their own learning, a meld or synthesis of these two descriptors seemed to be required. The interpretive tool which I designed for this thesis offers I believe, some reflective positions which might be adopted by practitioners when articulating their own learning and experience, or listening to the articulation of others: Situated Reflection – relates to an understanding of the underlying practice norms in a particular community. (This is how we do it here, this is my version of professionality) Strategic Reflection – relates to perception about how effectiveness might or might not be achieved in a given situation or issue. (Looking at all the permutations, this is the way to proceed in the future, reflection-on-action) Abstract Reflection – relates to the way a situation might be perceived by someone else outside of the ‘community’ perhaps. (It may look as if I am complying, but I have another agenda or I can think about this objectively without necessarily relating it to my own practice) Sentient Reflection – relates to sensitive awareness of personal feelings in any given situation, the affective domain, an awareness of cause/effect of action on self and others. (I or others may be emotionally affected by this, there is personal and emotional baggage attached to this issue.) Analogous Reflection – relates to the ability to consider a situation in other terms (analogy or metaphor perhaps) in order to understand it. (I don’t know what this is about, I need to look at it differently, I have to distance myself from this issue in order to make a rational judgement – suspension of judgement strategy.) Transformative Reflection – relates to a situation where the reflector transforms reflected experience at the moment of telling into ‘new-learning’ and may be aware of having done so. (Now that I think about it, of course that is the reason/outcome, no wonder that happened! I hadn’t thought of that before now, you sparked something off – an act of composure during a dialogic interview perhaps.) (Morgan, 2001) These new descriptors enabled me to have due regard for the inferences or allusions that were being made during interviews and within written statements: What type of reflection is this? To what practice, social or emotional situation might it be alluding? What importance is this practitioner attaching to this statement? Is this practitioner engaging in an act of composure or new learning? 82 Persuading participants to articulate their own learning is in some way the confrontation of principles with practice. This articulation is the act of recognising the conjunction and trying to talk about it, using as Mercer (1995) suggests ‘language as a means for people to think and learn together.’ In this respect my questions or my position as interviewer have acted as a change agent for a deeper or more critical reflection on practice. Because this dynamic has been evoked, I may not only be receiving considered ideas, but latent and emerging ones. Once articulated these will contribute to a reconsideration of practice by the respondent, and also become integral to his/her repertoire of ideas. This is an energetic dimension which corresponds to those ideas of ‘activity theory’ referenced previously. It produces a consciously collaborative process of exploration, which Knight and Saunders (1999:145) refer to ‘as the way in which we helped them to construct conscious accounts of their working milieux’. Freire (1972b:33, 1972a:68-69) talks about working with learners to ‘reflect critically on their experience’, through the negotiation of its key ‘contradictions’ and ‘generative themes’ (referenced by Winter 1999:189-90). Gadamer (1975:340) suggests that this process of understanding related to the hemeneutics of the issue ‘is disclosed as a dialectic of question and answer’. Mezirow (1991: 11) regards this dialectical process integral to the transformative nature of learning (an idea that will be further explored in the analysis section of this work). Schön (1991:61) suggests that this is an act of ‘resurfacing’ experience: ‘...he can surface and criticize the tacit understandings that have grown up around the repetitive experiences of specialised practice, and can make new sense of the situations of uncertainty or uniqueness which he may allow himself to experience.’(Schön in Sparrow 1998) Since it is impossible to ignore the constraints of everyday life, the interviewer according to Cicourel (1964) cited by Cohen and Manion (2000:267-8) ‘cannot bring every aspect of the interview encounter under rational control’. Therefore as Cohen and Manion suggest, the interviewer may need to seek ‘a theory of everyday life rather than a technique for dealing with bias’. Silverman (1993:97) refers to this as ‘common-sense knowledge of social structures’. ‘Ontological Oscillation’ - an interpretation dilemma: A particular challenge in terms of the interpretation of the meanings of the tutors in the case study (The Graduate and Postgraduate Centre) was that as a group they sit within two distinct cultures or ‘communities of practice’ (Wenger 1998). The tutors on the degree programmes are drawn from full time advisory staff of the LEA. It is as impossible to separate their practice as tutors from their practice as LEA Advisers, as it is to separate the person from the teacher (Head 1997) and indeed this latter aspect is also present in the dynamic of their own interpretation of particulars of practice. First and foremost they may have a view as a person who is a teacher which overrides their principal position of a ‘teacher-as-adviser’ and in their newly acquired role runs alongside ‘adviser-as-tutor’. Which of these ontology’s would be either expressed or repressed in their responses to my questions? Did these professionals oscillate between positions or come to some common understanding within them selves which reflects an amalgam of all three positions and thus a particular ‘community of practice’ which I believe to be unique? The various ‘roles’ occupied by the respondents at the time of the interviews 83