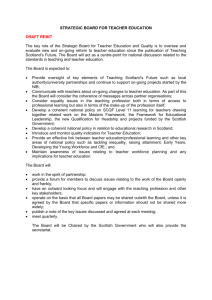

Housing and Health - The Scottish Government

advertisement

A SELECT REVIEW OF LITERATURE ON THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HOUSING AND HEALTH Scottish Government Communities Analytical Services September 2010 Analytical Paper Series Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………………………………………………………….3 SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………………..5 SECTION TWO: POLICY RESPONSES TO HEALTH AND HOUSING…………………………………………..6 SECTION THREE: HEALTH AND HOUSING RESEARCH……………………………………………………………8 SECTION FOUR: CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………………………….12 REFERENCES……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….15 2 Executive Summary General Links have been drawn between poor health and poor housing since the nineteenth century. The social gradient to health remains strong in contemporary societies, including Scotland. There is also a social gradient to housing, which is evidenced in the ability to access and retain particular tenures and neighbourhoods. Identifying the independent effects of housing on health and well-being is problematic since a multitude of factors are implicated. A wealth of studies have consistently documented statistically significant associations between poor housing conditions and poor health, whilst others have found less stringent relationships, but relationships nonetheless. Improvements to housing environments (internal and external) are likely to contribute towards improvements in particular physical health conditions, including mental health and well-being. Evidence on the relationship between poor housing and poor health suggests that a sustained commitment to joined-up policy - which is informed by that evidence - needs to develop further so that the national outcomes built around equality, improving health and tackling poverty, and enhancing opportunities can flourish. Health and Housing The greatest risks to health in housing are related to cold and damp (including moulds and fungus), which affect and exacerbate respiratory conditions. Indoor air quality, dust mites and other allergens. House type and overcrowding represent further examples of risk factors. Other less direct risks include neighbourhood effects such as a broad range of antisocial behaviour, which can have a negative impact on mental well-being. Some research highlights differences in health between those living in particular housing tenures. Housing conditions in homes that are owned tend to be better than in homes that are rented, especially in relation to problems of condensation, lack of adequate heating and damp, with proportions in the rented sector around twice as high. There are large numbers of homeowners living in poverty, which can contribute towards negative health outcomes, therefore, the relationship between tenure type and poverty needs rethinking. Housing problems are a component of the multiple disadvantages that combine to affect - and be affected by – health and well-being. A large body of research shows that improvements to housing conditions can produce health benefits. Policies which tackle fuel poverty are likely to deliver economic, and health and wellbeing benefits to many households. Health and Social Inequality On health and morbidity, Scotland performs worse compared to the rest of the UK and the European average. 3 Broader effects of housing Housing actively reinforces or reduces social inequality not only in health, but in other areas too, such as education and employment. Mental Health and Well-being Studies on housing type indicate that high rises and multi-dwelling accommodation can be detrimental to psychological well-being. Early findings from the Glasgow Gowell study suggest that mental health outcomes are generally poorer amongst high rise residents. The number of families experiencing housing stress is likely to be increasing during current economic difficulties, and a range of international research suggests that housing payment problems, insecurity and debt, can induce significant health stressors. The Scottish Health, Housing and Regeneration Project (SHARP) reports slight improvements in people’s health after a move (especially from a flat to a house) and some positive wellbeing and lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation, though the durability of such changes at the individual level is not known. 4 SECTION ONE: INTRODUCTION Aim and Method 1.1 This paper presents a discussion of the relationship between housing and health. Given the immense breadth of these areas, it has not been possible to produce an exhaustive review of research, nor to adopt a more complex meta-analytical approach. The search parameters were guided by strict time constraints, whilst the research method involved numerous combinations of search terms using web-based search engines and the University of Leeds portal to access electronic journals in housing studies; as well as searches of UK government websites for policy documents and to identify relevant research at the UK and Scotland level, and, where available, international research. 1.2 It should be remembered however, that in drawing international comparisons, different countries have different concentrations of social, rented and private sector housing and different ideologies which support the development of these, as well as different health systems. The paper therefore has limitations, but its aim is to encourage reflection on the relationship between housing and health in Scotland amongst policy makers and analysts. 1.3 Links have been drawn between poor health and housing since the nineteenth century. Statisticians and social commentators across Europe were increasingly interested in charting the conditions of the poor, primarily motivated by concerns to improve their living conditions. The relationship between various social factors had been surveyed by the ‘moral statisticians’ Quetelet and Guerry in Europe, whilst in Britain, Chadwick produced the General Report on the Sanitary conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain in 1842, alongside studies by Rowntree and Booth. In the following century, the Black Report (1980) proved fundamental to understanding the relationship between health and inequalities, recommending that greater emphasis be placed on the prevention of poor health. In particular, it argued that this could be achieved by improving the material conditions of life for disadvantaged groups, since there remained a clear class gradient in health, more marked in Britain than in many other countries. The social gradient to health remains strong and is explicitly recognised in the Marmot Review, which has gathered evidence and advised on the development of a contemporary health inequalities strategy in England (Fair Society, Healthy Lives, 2010). 1.4 The prevention of poor health can be targeted across various domains: at individual and social levels as well as at the physical environment. The attention to inequalities and social class which had been emphasised in the Black Report appeared to have little impact on the government’s impetus to improve housing conditions, however. There are a range of indicators which illustrate that although progress has been made since then, there is still a long way to go towards improving housing conditions, and this has implications for health and well-being. The English House Condition Survey for example, demonstrated that even in 1996, around 1 and a half million households were living in accommodation which did not meet the required standards (DETR, 2000). In the Scottish context, over ten years later, the Scottish House Condition Survey (SHCS) reported that 64% of dwellings failed the Scottish Housing Quality Standard (SHQS introduced in 2004), primarily on the energy efficiency 5 criterion, though there has been some improvement since 2004/5 (Scottish Government, 2008a: 32). There is no legal requirement however, for housing to comply with the SHQS. The Standard is a government target for the social sector to achieve by 2015 with an aspiration for the private sector to make it too. Amongst those household failing the SHQS, there is an above average percentage of people with either a long term illness, disability or both. The illnesses and disabilities that are most common amongst those living in households who have failed the SHQS includes a miscellaneous category of illness or disability, heart, blood pressure or circulation problems, problems or disabilities related to the feet or legs, chest or breathing problems, and arthritis. However, the issue of causality, that is, whether poor housing causes poor health or whether having poor health increases the likelihood of ending up in poor housing, is not at all clear, and there is no evidence from the SHCS that housing which fails the SHQS actually directly damages health. 1.5 Identifying the independent effect of housing on poor health is particularly complicated since a multitude of factors are implicated. It should be remembered however, that similar problems arise in seeking to determine the cause or causes of specific diseases and illnesses. Attempting to identify the causes of specific diseases like cancer or myocardial infarction, for example, is fraught with problems. Contributory factors can be identified, whose presence in greater or lesser combinations in particular individuals (in part dependent on behavioural and lifestyle factors), increases the risk of their development. Furthermore, a combination of known risk factors or exposure to a particular virus or bacteria does not necessarily result in the development of an associated disease in every case. It is therefore difficult to prove definitive causal factors in the development of particular diseases. In pragmatic terms there seems little point therefore, in getting caught up in debates which reflect on whether poor housing causes poor health, though there is clearly a relationship between particular housing factors and poor health, as this discussion explains. 1.6 The relationship between housing and health is complex and the causal links between different dimensions of housing, neighbourhood environment and health operate at a number of interrelated levels. Furthermore, poor housing conditions often coexist with other forms of deprivation (for example, low income, unemployment, poor education and social isolation), making it difficult to isolate, modify and assess the overall health impact of housing conditions (Taske et al, 2005:46). SECTION TWO: Policy Responses to Health and Housing 2.1 Scotland performs worse on health and mortality compared to the rest of the UK and the European average, including other smaller European countries. It is particularly striking that some European nations, despite having higher levels of poverty and deprivation, have healthier populations than Scotland (Scottish Government, 2008c), though this is likely to relate in part to such factors as cultural differences in food preferences and availability, prices and availability of other consumables such as alcohol and tobacco, as well as lifestyle factors. 6 2.2 There are various documents at both the UK and Scotland level which underscore the relationship between poor health and housing. Some of these refer to more general policy aims whilst others highlight specific policies designed to improve the relationship. The UK government’s commitment to promoting health and tackling health inequalities through policies concerned with housing, regeneration and sustainable development is set out in Tackling Health Inequalities: A Programme for Action (Department of Health, 2003). This states that actions likely to have the greatest impact over the long term include improving social housing conditions and reducing fuel poverty among vulnerable populations. Furthermore, key interventions that may contribute to closing the life expectancy gap include improving housing quality by tackling cold and dampness. Similarly, those that will contribute most to closing the gap in infant mortality rates relate to improving housing conditions for children in disadvantaged areas (Taske et al, 2005). 2.3 Fuel poverty is defined as the need for a household to spend over 10% of its income to achieve temperatures required for health and comfort. It arises from a combination of three factors: low income, fuel costs and energy efficiency, and is therefore intimately linked to housing condition and costs since households on low income tend to live in poorer quality housing. A household can be fuel poor even if it is in receipt of a relatively high income, depending on the price of fuel and the energy efficiency characteristics of buildings. Fuel poverty is more common in Scotland than income poverty, and proportionately higher than the levels in England (Scottish Government, 2008a:40). 2.4 The Scottish Government’s target to eliminate fuel poverty is set for November 2016 (with the caveat, as far as is reasonably practicable), and is part of its commitment to creating a more successful country (Scottish Government, 2008a:41). Scotland has operated a Central Heating Programme and the Warm Deal Programme to insulate homes to improve energy efficiency as a way of addressing householders’ potential fuel poverty1. There is no clear evidence however, according to Equally Well, that there are health gains to be secured from the alleviation of fuel poverty (Scottish Government, 2008b). 2.5 There are complex interactions between a multiplicity of individual, physical and social factors which impact on health inequalities. Equally Well details Scotland’s policy on health inequalities, including focusing specific attention to housing and other domains. The report begins by highlighting socio-economic status inequalities in health, where causes include specific exposures such as damp housing, hazardous work or neighbourhood settings, behaviours, such as smoking and diet, and personal strengths and vulnerabilities. Mechanisms can be physical, psycho-social, behavioural or a combination of each (ibid, p6). The report also highlights the characteristics of policies most likely to be effective in reducing inequalities in health including structural changes in the environment, such as installing affordable heating in cold, damp housing to help alleviate fuel poverty; legislative and regulatory controls such as house building standards; and improving the accessibility of services such as better transport links and the location of core services. The report also discusses the significant health inequalities in Scotland in terms of mortality, physical illness, 1 The Energy Assistance Package replaced the Warm Deal and Central Heating Programme from April 2009 which aims to deliver a combination of fuel poverty and wider poverty, climate change and energy objectives in a coordinated manner (Scottish Government, 2009c). 7 mental health and well-being, lifestyle behaviours associated with ill health and access to and use of health services (ibid, p12). 2.6 Equally Well highlights three key areas that need to be addressed in order to tackle health inequalities. These include education, employment and worklessness, and the physical preconditions of health. It is recognised that the physical conditions in which people live exert a significant impact on health, and that environmental policy is one of many important facets in addressing health inequalities. In terms of housing specifically, the Scottish Government recognises that quality housing is necessary for good physical and mental health, that homelessness is best tackled through partnership working (to meet the 2012 target), and that quality, affordable, accessible and sustainable housing is delivered across all tenures. Whilst the report underlines the correlation between poor housing and ill health - including neighbourhood characteristics, such as crime - it emphasises the difficulties in proving that poor housing actually causes ill health. A corollary of this is that it is difficult to identify what specific forms of action should be taken that might reduce health inequalities; however, it is recognised that, more general action on poverty, employment and physical and social environments will interact with housing improvements positively and should serve to improve people’s health and reduce health inequalities, if action on housing is sufficiently targeted (ibid, 76). 2.7 The UK government’s key framework for securing a decent home for all is set out in the Communities Plan (ODPM, 2003). The corresponding public service agreement target aims to bring all social housing into a ‘decent condition’ by 2010. To be considered ‘decent’ a dwelling must meet the statutory minimum standard for housing; be in a reasonable state of repair; have reasonably modern facilities and services, and provide a reasonable degree of thermal comfort. The Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS) is the UK government’s new approach to the evaluation of the potential risks to health and safety from any deficiencies identified in dwellings. 2.8 In Scotland, the Scottish Housing Quality Standard (SHQS) is the principal means by which housing quality is measured, using five broad criteria which a dwelling must possess in order to meet its requirements. Scotland’s objective in this respect is that all social housing should meet the SHQS criteria by 2015. Overall failure rates in the socially rented stock have fallen from 77% in 2002 to 60% in 2005-6, which means there remains room for considerable progress, particularly in meeting the energy efficiency criteria (DEFRA, 2008: 17). Moreover, the Scottish House Condition Survey reports very high levels of disrepair, especially for older dwellings, and amongst a greater proportion of social sector dwellings than the private sector (Scottish Government, 2008d: 36). 2.9 The UK government’s A New Commitment to Neighbourhood Renewal: National Strategy Action Plan (Social Exclusion Unit, 2001) is viewed as a central focus for addressing multiple aspects of deprivation experienced in the poorest areas. A recent review of this strategy stated that poor quality housing, badly maintained local environments, problems with antisocial behaviour and crime and disorder, including drug and alcohol misuse, can cause instability in many deprived areas (Strategy Unit, 2005). This exacerbates local economic problems, as residents who are generally better skilled and educated move out, 8 leaving behind increasing concentrations of deprivation. Areas of low housing demand are more likely to suffer crime, vandalism and litter, and those living in social housing estates are five times more likely to perceive local disorder and antisocial behaviour as a problem. These problems are often compounded by social housing policies in which housing allocations can lead to further concentration of the most deprived in a particular area. Indeed there is a body of evidence which shows that residential sorting concentrates disadvantage and social exclusion, and that such neighbourhoods acquire characteristics which reduce opportunities for residents, limits their quality of life and contributes to a sense of powerlessness and alienation (Lupton and Power, 2002). 2.10 In Scotland, equivalent policy is presented in Achieving Our Potential (Scottish Government, 2008e). This highlights the importance of the National Performance Framework in delivering Solidarity. The Framework complements the Early Years Framework (2009a), and Equally Well (2008b), which together aim to address disadvantage in Scotland. Longer term measures to tackle poverty in Achieving Our Potential include delivering good quality housing, regenerating disadvantaged communities, providing children and young people with the best start in life, dealing with health inequalities, and promoting equality. SECTION THREE: Health and Housing Research 3.1 There are a wealth of studies which have consistently documented statistically significant associations between poor housing conditions and poor health (e.g. Acheson, 1998; Evans, 2003; Ineichen, 1993; Marsh et al., 2000; and reviewed by Shaw, 2004; Taske et al, 2005). The greatest risks to health in housing are related to cold and damp (including moulds and fungus), which affect and exacerbate respiratory conditions. In Scotland, findings from the Scottish House Conditions Survey indicate that around 1 in 10 dwellings have condensation in at least one room, though few suffer from rising or penetrating damp. Indoor air quality, dust mites and other allergens, house type and overcrowding constitute further risk factors (internal paper Communities Analytical Services, 2009). Other risks are less direct (neighbourhood effects), including a broad range of antisocial behaviour, which can have a negative impact on mental well-being. In addition, neighbourhood deprivation increases the risk of poor health, even after controlling for individual risk characteristics, such as poor socio-economic status (Diez Roux et al., 1997; Kawachi and Berkman, 2003). A review by the Prime Minister’s Strategy Unit (Strategy Unit, 2005) found that poor health in deprived neighbourhoods is in part driven by a series of social and environmental factors, including poor housing and local environments, limited social networks, income, poverty and worklessness, poor local transport and access to services, low educational attainment and drug and alcohol misuse. 3.2 The association between housing conditions and physical and mental ill health has long been recognised and there are a broad range of specific elements related to housing that can affect health outcomes (Bonnefoy et al., 2004). These include agents that affect the quality of the indoor environment such as indoor pollutants, cold, damp, housing design or layout (which in turn can affect accessibility and usability of housing); factors that relate more to the broader social and behavioural environment such as overcrowding, sleep deprivation, and neighbourhood quality, and factors that relate to the broader macro-policy 9 environment such as housing allocation. Indeed according to the authors of Housing and Public Health: It is likely that the causal link between housing and health works in both directions, with housing affecting an individual’s health, and health also affecting an individual’s housing opportunities. There also appears to be a ‘dose response’ relationship between poor housing and ill health, with increased housing deprivation at one point increasing the probability of ill health; and a sustained experience of housing deprivation over time further increasing the probability of ill health (Taske et al, 2005:13) 3.3 There also appears to be a significant link between housing deprivation early in life and ill health in adulthood, with poor housing in childhood associated with higher rates of hospital admissions and increased morbidity and mortality in adult life (Marsh et al., 1999). Shaw (2004) has constructed a useful model for conceptualising the relationship between housing and health. The model indicates how housing affects health through direct and indirect, and ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ ways. Softness refers to the ways in which housing can influence health through its poor quality, as well as insecurity and debt, general well-being, feelings of ontological security and social status perception. 3.4 Poor quality is especially indicated in studies on housing type, with high rises and multi-dwelling accommodation evidenced as detrimental to psychological well-being, particularly for mothers with young children (Evans, Wells and Moch, 2003). There is also some evidence of this in the Scottish context, revealing a negative relationship between poor housing type and mental health which is particularly stark in those areas where levels of social renting are greatest. Indeed, when considering a broad range of indicators of poverty, ill health and social exclusion, Glasgow stands out as qualitatively distinct and is at the bottom of Scotland’s league tables2, with inequalities continuing to grow (Gowell, 2008). As Scotland’s largest city, thousands of high rises were built from the 1960s onwards. Many of Glasgow’s high rise and socially rented housing are located in areas of considerable deprivation, though according to findings from Scotland’s Gowell programme, many residents of social rented high rises are happy with their homes and neighbourhoods. 3.5 One of the aims of the Scottish Government funded Gowell study is to explore the effects of regeneration on those living in high rises in predominantly social renting neighbourhoods and its relationship to health and well-being. Early findings suggest that mental health outcomes are generally poorer amongst high rise residents. In addition, the research indicates that smoking, diet and exercise habits are also poorest amongst this population compared to those from other dwellings, including other types of flats and other houses in predominantly socially renting neighbourhoods (Gowell, 2009). High rise flats also perform less well for their residents on other measures including feelings of relative status, personal progress in life, and degree of fit between the dwelling type and personality and the values of the occupant (ibid, 2009). In the European context, Scotland’s health does not perform well (usually worst in males). Lung cancer rates are particularly high, and largely associated with smoking. See A.T.B. Moir http://www.rcpe.ac.uk/journal/issue/journal_32_4/8_scotland_health.pdf 2 10 3.6 Evans (2003) also presents evidence on the relationship between housing and poor health identifying key stressors which include insecurity and tenure concerns, difficulties with landlords and repairs, frequent relocations, limited control over social interactions, and the stigma of poor housing. Additional factors have been identified by Bonnefoy et al (2004). Poor quality housing increases the likelihood of experiencing ill health, as does fear of losing the dwelling (insecurity). A bad image of the neighbourhood also has important health implications. For Shaw (2004), household dwellings are also important as homes in their own right, in providing ontological security, whilst Bonnefoy (2007) highlights the centrality of the home to promoting the growth of relationship development and intimacy amongst householders. 3.7 The number of families experiencing housing stress is likely to be increasing during the current economic difficulties, and a range of international research suggests that housing payment problems, especially insecurity and debt, can lead to significant health stressors. Yates and Milligan’s (2007) study in Australia for example, has illustrated that such stress contributes not only to health problems but impacts on family relationships. Moreover, financial difficulties in meeting housing costs affect other areas of life, like children missing out on school activities. Indeed for Robinson and Adams, ‘housing problems are another component of the multiple disadvantages that can combine to affect (and be affected by) health and well-being’ (2008: 5). 3.8 There is a considerable body of research which has explored the links between housing stress and the mental well-being of families (cf. Robinson and Adams, 2008). A large-scale Canadian study, for example, found a gradient in mental health status by housing tenure, from less stress amongst homeowners without mortgages, to most stress amongst renters (Cairney and Boyle, 2004). However, in the context of current economic difficulties with unemployment and large numbers of home-owners in arrears, the suggestion that home owners are likely to experience better mental health is open to challenge, and may be more pertinent in times of economic stability. 3.9 Few studies have explored the relationship between housing and health over time. Indeed, longitudinal data is particularly important for policy since it is the most robust methodology for enabling causal relationships to be drawn and for revealing patterns. Pevalin et al (2008) sought to address this gap by drawing on longitudinal data from the British Household Panel Survey. Their findings, based on the use of statistical techniques and longitudinal data to plot changes in housing conditions and their link to changes in health, reveal a dynamic relationship between housing conditions and health. They maintain that improvements in housing conditions do produce health benefits. Crucially, their research has illustrated that, Worsening housing conditions . . . are independently associated with deterioration in health, especially the number of reported health problems in women (2008: 679). 3.10 The policy implications of these findings are significant, particularly for women, but also in terms of policies directed at addressing the conditions of particular tenure types. The research suggests that improvements to women’s mental well-being can be addressed by 11 improvements in the housing environment (for example by addressing vandalism and noise pollution in the local vicinity), and also improvements to health by improving the physical condition of housing. 3.11 There is a also a clear difference between homes that are owned and those that are rented, especially in relation to problems of condensation, lack of adequate heating and damp, with proportions in the rented sector around twice as high (Pevalin et al,, 2008: 684). In Scotland, the Scottish House Conditions Survey (SHCS) reports that around 1 in 10 homes have condensation in at least one room (SHCS, 2008). These findings should also be considered in the context of earlier research which drew on the Poverty and Social Exclusion Survey of Britain (Kawachi and Berkman 2003). This observed that home ownership and poverty have rarely been linked together, and that half of those living in poverty in Britain today are homeowners, concluding therefore that perceptions about tenure type and poverty need rethinking. Indeed, a Scottish Government report on fuel poverty indicates that levels of fuel poverty are highest in owner occupied dwellings and lowest in the social renting sector (Scottish Government, 2008a). Scottish data from the SHCS also indicates that the private housing sector (including private rented) performs considerably less well than the social sector on a number of indicators including condensation, dampness and heating (including satisfaction with heating and difficulty heating the home) (SHCS, 2008). 3.12 Scotland’s Gowell project is a longitudinal study designed to investigate the impact of investment in housing, regeneration and neighbourhood renewal on the health and wellbeing of individuals, families and communities over a ten-year period, beginning in 2006. The programme is a multidimensional, longitudinal evaluation of Glasgow’s housing regeneration programme focusing on the health and well-being of residents in 14 study areas (Gowell, 2008). The sample includes around 6,000 adults. The baseline survey has indicated that the physical, social and service environments to be provided in transformation areas should be capable of enhancing the psychosocial benefits people derive from homes and neighbourhoods in which they live, and that there has been some change in psychosocial benefits in major transformation areas, with people in houses performing best, followed by flats and high rises (Scottish Government, 2008b; for detailed discussion see unpublished Gowell, 2009). However, the findings cannot be attributed solely to regeneration since other public policy and wider social and economic developments have occurred simultaneously. In addition, the longitudinal Scottish Health, Housing and Regeneration Project (SHARP) offers useful insights into housing and neighbourhood transformation (Gibson et al, 2008). This is a study of the health and social impacts on tenants which result from moving into new-build socially rented housing. In particular, the survey found that the psychosocial benefits of moving were greatest for those who moved from a flat to a house. The study also reports slight improvements in people’s health after a move and some positive wellbeing and lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation, though the duration of such changes at the individual level remains to be seen. 3.13 Pevalin et al’s research on the relationship between housing and health strongly urges health and housing debates, as well as policy makers, to move away from inconclusive debates which seek to explain why research has failed to establish a causal relationship between poor housing and ill health, and to, 12 Accept that associations exist, that housing has a role to play in both physical and mental health, and that some types of house condition are more perilous to health than others (Pevalin et al, 2008:695). 3.14 Indeed, Taske et al’s review of evidence (2005) presents a wealth of material which indicates a strong and convincing relationship between poor health and poor housing. The review also sought to identify which housing related interventions work to promote health for all population groups, but with particular reference to disadvantaged and vulnerable groups. 3.15 Evidence suggests that particular communities suffer disproportionately in housing (CRE, 2003). Overcrowding is one of many factors that can adversely affect health, although in common with other housing-related components, this can interrelate with other factors so that it is difficult to measure its precise effect. For example, according to Taske et al (2005) overcrowding, family income, energy efficiency, design and location of the property may in turn influence other housing-related factors, such as damp, cold, noise penetration, smoking behaviour and indoor air quality (Taske et al, 2005). 3.16 Arthurson and Jacobs’ (2004) discussion of housing policy in Australia underlines the broader effects of social exclusion which exists not only on housing estates, but within the owner occupied and low income private rental housing sectors. Moreover, the interconnected aspects of deprivation mean that housing policies need to adopt a joined-up government approach that coordinates housing policy with investment in education, health, transport, crime prevention and employment. Housing actively reinforces or reduces social inequality not only in health, but in other areas too, such as education and employment (cf. Arthurson and Jacobs, 2003). SECTION FOUR: Conclusion 4.1 This paper has explored the link between housing and health, or more specifically between poor housing and poor health; though even good quality housing can be linked to negative health effects where householders are struggling to maintain payments or there are neighbourhood problems. The relationship between housing and health is complex and the causal links between different dimensions of housing, neighbourhood environment and health operate at a number of interrelated levels. Furthermore, poor housing conditions often coexist with other forms of deprivation, for example, unemployment, poor education, ill health, and social isolation, making it difficult to separate, modify and assess the overall health impact of housing conditions. However, research shows that housing and the immediate neighbourhood environment can impact on health in a number of ways. Poor quality housing can exacerbate respiratory conditions like asthma, which has serious and sometimes life threatening consequences. Indoor air quality, dust mites and other allergens, house type and overcrowding are further examples of risk factors associated with housing. Other less direct risks to health include neighbourhood effects such as a broad range of antisocial behaviour, which can have a negative impact on mental well-being, and the general quality of local environments, which includes the capacity to build positive social 13 networks, income, poverty and worklessness, poor local transport and access to services, low educational attainment and drug and alcohol misuse. 4.2 Good mental health is recognised by the Scottish Government as an important component of a healthier lifestyle, better physical health, and better relationships with family and friends and in achieving greater productivity in the workplace. Scotland's mental health improvement plan, Towards a Mentally Flourishing Scotland (Scottish Government, 2009b), highlights the contribution that improved mental health can make towards achieving one of its strategic objectives to create a more successful Scotland which offers everyone the opportunity to reach their full potential. The report makes clear that reducing mental health problems is important for the healthy functioning of communities since it impacts on behaviour, social cohesion, social inclusion, crime and prosperity. The report indicates further the importance of the physical environment to mental health including noise levels, building design, and secure tenure (Scottish Government 2009a:29). One of the commitments to creating mentally healthy communities involves exploring the relationship between children’s health and the physical environment. 4.3 The Scottish Government, in implementing Good Places, Better Health (Scottish Government, 2008c), is concentrating on four child health priorities including mental health improvement, and recognising that the physical environment influences health. The report supports five national outcomes: that children have the best start in life and are ready to succeed; that people live longer, healthier lives; that the significant inequalities in Scottish society are tackled; that people live in well-designed, sustainable places where they are able to access the amenities and services they need; and that people value and enjoy the built and natural environment and protect and enhance it for future generations. 4.4 Combating ill health through addressing its association with poor housing is likely to deliver a broad range of social and economic benefits which will go some way towards achieving the Scottish Government’s purpose and various national outcomes. For children, young people and families more generally, addressing poor housing can improve their life chances by augmenting health and well-being, which in turn will boost educational and employment performance, at the very least by reducing numbers of lost school and work days and increasing productivity. Tackling the links between poor housing and poor health will also go some way towards addressing inequalities more generally, since the most disadvantaged groups tend to live in the worst types of housing. Glasgow is particularly instructive here, since it has the highest concentrations of multiple deprivation in Scotland. Many aspects of health and quality of life in the city and its environs compare poorly with the rest of the country (Gowell, 2009). 4.5 Evidence on the relationship between poor housing and poor health suggests that a sustained commitment to joined-up policy, informed by a robust research base, needs to develop further so that the national outcomes built around equality, poverty and enhancing opportunities can flourish. Dr Susan Wiltshire Housing Research 14 Bibliography Acheson, D. (1998) Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health: Report The Stationery Office , London. Arthurson, K and Jacobs, K (2003) Social Exclusion and Housing AHURI Southern Research Centre, Final Report No 51 http://www.ahuri.edu.au/search.asp?sitekeywords=40199&CurrentPage=1 (accessed 15/01/2010) Black, D., Morris, J., Smith, C. and Townsend, P. (1980) Inequalities in Health: Report of a Research Working Group Department of Health and Social Security , London. Bonnefoy, X., Annesi-Maesano, I., Aznar, L., Braubach, M., Croxford, B., Davidson, M. et al. (2004, June). Review of evidence on housing and health. Paper presented at the Fourth Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health, Budapest, Hungary in Robinson, E and Adams, R (2008) Housing stress and the mental health and well-being of families, AFRC Briefing 12. Bonnefoy, X. (2007). Inadequate housing and health: an overview. International Journal of Environment and Pollution, 30(3/4), 411-429. Cairney, J., & Boyle, M. (2004). Home ownership, mortgages and psychological distress. Housing Studies, 19(2), 161–174. Chadwick, Edwin. Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain. 1842. Ed. & Intro. M.W. Flinn. Edinburgh: University Press, 1965. Communities Analytical Services (2009) ‘Housing Quality Improvements and Health Inequalities. Scottish Government Internal paper. Commission for Racial Equality (2003) National Analytical Study on Housing RAXEN focal point for the United Kingdom European monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia. DEFRA (2004). The UK Fuel Poverty Strategy. 2nd Annual Progress Report. London: Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (2000) English House Conditions Survey HMSO , London. Department of Health (2003) Tackling Health Inequalities: a programme for action. London: Stationery Office. DEFRA (2008) The UK Fuel Poverty Strategy, 6th Annual Progress Report. London: Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform 15 http://www.berr.gov.uk/files/file48036.pdf (accessed 13/01.2010) Diez-Roux, A. V., Nieto, F. J., Muntaner, C., Tyroler, H. A.,Comstock, G. W., Shahar, E., Cooper, L. S., Watson, R. L. and Szklo, M. (1997). Neighbourhood environments and coronary heart disease: multilevel analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology 146: 48-63. Evans, G. W. (2003) The built environment and mental health. Journal of Urban Health 80 , pp. 536-555. Evans, G., Wells, N., & Moch, A. (2003). Housing and mental health: A review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique. Journal of Social Issues, 59(3), 475– 500. Gibson M, Thomson H, Petticrew M and Kearns A (2008) Health and Housing in the SHARP Study: Qualitative Research Findings, Scottish Government. Gowell (2008) Public Health, Housing and Regeneration: what have we learned from history? Glasgow Community Health and Well-being Research and Learning Programme, April 2008 http://www.gowellonline.com/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=30&Ite mid=67 (accessed 21/01/10) Gowell (2009) Health, Well-being and Deprivation in Glasgow and the Gowell Study Areas, Glasgow Community Health and Well-being Research and Learning Programme, January 2009 http://www.gowellonline.com/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=30&Ite mid=67 (accessed 21/01/10) Ineichen, B. (1993) Homes and Health: How Housing and Health Interact E & FN Spon , London Joseph Rowntree Foundation (2008) ‘Developing safety nets for home-owners’, March 2008 http://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/2198-mortgage-insurance-repossession.pdf (accessed 4/12/09) Kawachi, I. and Berkman, L. F. (2003). Neighbourhoods and health. Oxford University Press. Lupton, D and Power, A. (2002) Social Exclusion and Neighbourhoods, in J. Hills et al (eds.) Understanding Social Exclusion, Oxford: Oxford University Press Marmot Review (2010) Fair Society, Healthy Lives, Strategic Review of Health Inequalities in England post-2010 http://www.ucl.ac.uk/gheg/marmotreview (accessed 18/02/10) 16 Marsh, A., Gordon, D., Pantazis, C. and Heslop, P. (1999). Home sweet home? The impact of poor housing on health. Bristol: Policy Press. Marsh, A., Gordon, D., Heslop, P. and Pantazis, C. (2000) Housing deprivation and health: a longitudinal analysis. Housing Studies 15 , pp. 411-428. NHS National institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2005) Evidence briefing, December http://www.nice.org.uk/niceMedia/pdf/housing_MAIN%20FINAL.pdf (accessed 08/01/2010) ODPM (2003). Communities Plan (Sustainable communities: building for the future). London: Office of the Deputy Prime Minister. Palmer, G North, J Carr, J and Kenway, P (2003) Monitoring Poverty and Social Exclusion http://www.jrf.org.uk/publications/monitoring-poverty-and-social-exclusion-2003 (accessed 4/12/2009) Pevalin, D J, Taylor M P, Todd J (2009) ‘The dynamics of unhealthy housing in the UK: A panel data analysis’ Housing Studies, Vol 23, Issue 5, Sep 2008. pp. 679-695. Robinson, E and Adams, R (2008) ‘Housing stress and the mental health and well-being of families’, AFRC Briefing 12. http://www.aifs.gov.au/afrc/pubs/briefing/b12pdf/b12.pdf (accessed 18/12/09) Scottish Government Statistics 2007/2008 Social and Welfare – Income and Poverty – Main Analysis http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Statistics/Browse/SocialWelfare/IncomePoverty/CoreAnalysis#a11 (accessed 14/05/2010) Scottish Government (2008a) Review of Fuel Poverty in Scotland http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/BuiltEnvironment/Housing/access/FP/fuelpovertyreview (accessed 14/01/2010) Scottish Government (2008b) Equally Well: Report of the ministerial taskforce on health equalities Volume 2 http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2008/06/25104032/0 (accessed 3/2/10) Scottish Government (2008c) Good Places, Better Health: A new approach to the environment and health in Scotland: Implementation Plan, December 2008 http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2008/12/11090318/2 (accessed 21/01/10) 17 Scottish Government (2008d) Scottish House Condition Survey: Key Findings 2008 http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/292876/0090383.pdf (accessed 22/1/10) Scottish Government (2008e) Achieving Our Potential: A Framework to tackle poverty and income inequality in Scotland http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2008/11/20103815/0 (accessed 3/2/10) Scottish Government (2009a) The Early Years Framework http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Publications/2009/01/13095148/0 Scottish Government (2009b) Towards a Mentally Flourishing Scotland: Policy and Action Plan 2009-2011, May 2009 http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/271822/0081031.pdf (accessed 21/01/10) Shaw, M. (2004) Housing and Public Health. Annual Review of Public Health 25 , pp. 397418. Social Exclusion Unit (2001). A new commitment to neighbourhood renewal: national strategy action plan. London: Cabinet Office. Strategy Unit (2005). Improving the prospects of people living in areas of multiple deprivation in England. London: Cabinet Office. Taske, N; Taylor,L; Mulvihill, C and Doyle, N. (2005) ‘Housing and public health: a review of reviews of interventions for improving health’. Evidence Briefing NICE. Yates, J., & Milligan, V. (2007) ‘Housing affordability: A 21st century problem. National research venture 3: Housing affordability for lower income Australians’ (AHURI Final Report No. 105). http://www.ahuri.edu.au/publications/download/nrv3_final_report (accessed 18/12/09) 18