obstetric tutorial

advertisement

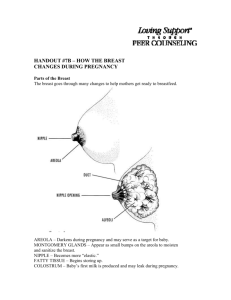

G:\OFFICE\WORD\NUNN\TRAINING\TUTORIAL\1TUT-EVL.DOC BMJ 2001;323:652 ( 22 September ) Suboptimal antenatal care implicated in half of stillbirths Susan Mayor London Suboptimal antenatal care might have contributed to the outcome in up to half of stillbirths recorded in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland during 1996 and 1997, says a report published last week by the Confidential Enquiry into Stillbirths and Deaths in Infancy. The eighth annual report—published as part of enquiry’s ongoing remit to identify areas of suboptimal care contributing to the deaths of babies between 20 weeks’ gestation and 1 year of age—showed that stillbirth remained the commonest category of death in this age group. It accounted for 3216 of the 10 139 deaths notified to the Enquiry for 1999. Reviewing stillbirths for an earlier period, 1996-7, the multidisciplinary enquiry panel said that "nearly half had suboptimal care that might have contributed to the outcome." Problems included: lack of coordinated antenatal risk assessment and referral practices throughout pregnancy; poor recognition and management of growth restricted babies; issues related to fetal movement (failure to act on reduced movements reported by mothers); communication (lack of planning, poor documentation; and lifestyle issues (smoking, poor attendance). Mary Macintosh, clinical director of the enquiry, said: "We need evidence based guidelines for health professionals working in antenatal care on how to manage problems such as growth restricted babies." She also said there was a need for better coordination among different members of the antenatal care team, within hospitals and between staff working in hospitals and those in the community. "During our review, we found that problems were sometimes detected but no action was taken. For example, a scan may have picked up possible growth restriction, but the result was not always plotted and followed through." On a more positive note, the report showed improved survival of babies born between 27 and 28 weeks’ gestation in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland between 1998 and 2000. Most babies (88%) survived to day 28. "This is almost double the rate observed 15 years ago," Dr Macintosh pointed out. She said that several factors had improved survival of premature babies, including giving steroids antenatally to women in premature labour and use of surfactants in premature babies after delivery. Networked care had also improved outcomes, as shown by the finding that survival had improved across all types of hospitals. Copies of the 8th annual report are available from the CESDI Secretariat, Chiltern Court, 188 Baker Street, London NW1 5SD (tel: 020 7486 1191) price £7. The report is also published on the internet at www.cesdi.org.uk Weeks By Venue Screening Early GP Surgery Medical and obstetric history. Arrange booking (sign form). Folate advice. 10-11 Midwife surgery Risk asessment. Discuss AFP screening. Booking bloods. 12 Obstetrician surgery 16 Midwife Maternity unit (AFP blood test. ) 20 Obstetrician Mather unit Anomoly / dating scan 25-26 GP Surgery BP check. Urinalysis. Foetal growth. Foetal heart. 28 Midwife Maternity unit BP check. Urinalysis. Foetal growth. Foetal heart. Routine bloods. 32 Midwife Maternity unit BP check. Urinalysis. Foetal growth. Foetal heart. Routine bloods. 36 GP Surgery BP check. Urinalysis. Foetal growth. Foetal heart. 38 Midwife Maternity unit Presentation. BP check. Urinalysis. Foetal growth. Foetal heart. 40 Midwife Maternity unit Presentation. BP check. Urinalysis. Foetal growth. Foetal heart. 41 Obstetrician Maternity unit Presentation. BP check. Urinalysis. Foetal growth. Foetal heart. Discuss induction of labour and give date if required. +6 GP Surgery Postnatal examination. The Antenatal Serology Programme The microbiology laboratory has no programme of routine testing for VZ antibodies in pregnancy as part of the booking blood serology. The presence of IgG in this specimen is indicative of immunity, acquired from previous exposure, and thus the pregnant patient and her foetus are protected, as reinfection is not seen in the inunune patient. If a pregnant patient is in contact with chickenpox, the problem should be discussed in the first instance with the consultant microbiologist. In pregnancy, there are several aspects to consider: · The impact on the mother. · The impact on the developing foetus. · The consequences of infection late in the pregnancy. Among the obvious measures to minimise the spread of infection to pregnant women are the following: Pregnant women should be discouraged from visiting or helping at playgroups or nurseries when chickenpox is prevalent in the community, and children with chickenpox should not attend antenatal clinics with their mothers. 2 The impact on the mother - primary chickenpox infection Based on serological studies, 80-85% of adults have had chickenpox in childhood, but the remaining 15% are more likely to develop complications if they have chickenpox as an adult, and infection in pregnancy is particularly likely to be complicated. Complications include: pneumonitis, haemorrhagic chickenpox and encephalitis. Mortality is significant, and morbidity high. This is particularly true of pneumonitis. If a pregnant woman reports contact with chickenpox, an attempt should be made to ascertain a history of previous infection. Check, in the first instance, whether her antibody status is recorded on the laboratory computer. If she has antibodies, there is nothing to be done; simply reassure the patient. If she has no recorded result, and the patient cannot remember having chickenpox or shingles, her mother or other relatives may be able to confirm the history. Appropriate skin scars may be taken as evidence of infection in the past. If the history remains uncertain, the antibody status can be confirmed serologically. Contact should be made with the Consultant microbiologist to discuss the problem and to arrange for serology if it is agreed that that is appropriate. Seropositive: reassure the patient, who is protected, as is the foetus. Seronegative: 1. Contact has been no more than 72 hours (or so) ago; offer VZIg. 2. Contact more than 72 hours ago, but less than three weeks ago; VZIg is increasingly less useful with increasing time interval, and of little value after ten days since contact. Women who develop chickenpox can be treated with Acyclovir, usually in hospital. 3. Contact more than three weeks ago; the incubation period is past, and with it the possibility of infection; reassure. The impact on the foetus - congenital varicella syndrome This can occur up to 20 weeks gestation, and in form it ranges from multisystem involvement and neonatal death to limb hypoplasia, or minimal skin scarring. With a maternal primary infection, the risk of this is about 1%, being maximal at 2% at 13-20 weeks. There is no method at present for prenatal diagnosis, though ultrasound may detect limb deformities, but this may be too late to intervene. The rationale for offering VZIg is the potential protection offered to the mother, who has a high risk of severe complicated disease, and is not primarily to protect the foetus. The consequences of infection late in the pregnancy Foetal infection rate is around 50% if the mother has chickenpox in the last 4 weeks of the pregnancy, and one third of these babies will develop clinical varicella in utero (NOT congenital varicella sydrome). If a non-immune pregnant woman has contact with chickenpox in the period one week before to one week following delivery, the baby should have VZIg, as it will have no passive maternal antibodies, and the risk of life-threatening encephalitis is high at this time. Laboratory Arrangements Out of Hours VZ antibodies can be measured any weekday, though the antenatal routine tests are done in a batch once a week. The test may be done as an emergency at weekends, when to wait till Monday might be too late for treatment to be effective. This MUST be agreed by the consultant microbiologist on call, and will rarely be necessary. Depending on the result, VZIg will be issued to you from the Area Laboratory if necessary. 3 Breast feeding policy The WHO recommends that all babies are breast fed for at least the first 6 months of life, and that breast fed babies need no other food or drink for the first 4-6 months of life. Northumbria Health Care Trust aim to encourage and support breastfeeding mothers and their families. No commercial information encouraging the use of artificial milks will be displayed within the Maternity Unit. All Health Centres and Antenatal clinics should have prominently displayed and easily available information on breastfeeding and its benefits. All Health Care professionals who care for mothers and babies should be fully aware of breastfeeding benefits and actively encourage and help mothers to establish and maintain successful breastfeeding. Breastfeeding has many advantages to both mother and baby: Breast milk provides complete nutrition for at least the first 4 months of life. It provides increased, protection against infections such as diarrhoea, gastro-enteritis, chest infections, wheezing and ear infections. Colostrum, which is produced in the first 2 or 3 days is especially high in antibodies to help fight infections. Babies who are breastfed tend to have lower blood pressure, better mental development, and may also be protected against childhood eczema and diabetes. Breastfed babies have less likelihood of cot death. Mothers who breastfeed have a lower risk of pre-menopausal breast cancer and a lower risk of ovarian cancer. They are also likely to have stronger bones in later life. Breastfeeding can help mothers to regain their pre pregnancy figure more quickly. Breastfeeding is cheaper than bottle feeding. Breastfeeding is more convenient than bottle feeding - no ste rilisation arid making up of bottles. Breast milk is free of germs, ready on demand and always at the right temperature. (UNICEF AND WORLD HEALTH ORGANISATION) Breastfeeding should be as unhurried and stress free as possible. Privacy should be maintained if required and the mother encouraged to find a comfortable position in which to feed. It is preferable to feed the baby immediately to prevent it becoming too distressed before being offered the breast, particularly if the mother lacks confidence in handling her baby. The mother should be shown verbally how to latch her baby on with as little "hands on" interference from the midwife as possible. It is very important to give praise and encouragement at this point, avoiding negative phrases which may diminish the mother's confidence in her ability to breast feed. The baby should be placed facing the breast with his head, shoulders and body in a straight line. His neck should be slightly extended so that his chin is against the breast and his nose or top lip is opposite the nipple. The baby should always be moved to the breast, not the breast to the baby. The nipple should be gently brushed against the baby's mouth to elicit the search reflex. Once his mouth is gaping wide he should take the nipple in his mouth. Mothers should be warned that it is normal to feel a sudden pain for the first few sucks. If feeding is painful for longer than this it may be a sign that the baby is not properly attached and the mother should be shown how to gently ease her baby off the breast before trying again. The mother should be reassured that this initial sharp pain will only last for a few days. All babies should be roomed in with their mothers to enable them to get to know their own babies' signals as quickly as possible and to allow quick access to the baby when he needs a feed. However it is 4 recognised that some mothers may need help with their baby, particularly through the night, or if the mother has had a difficult birth and is exhausted or in pain. Exhausted mothers need to be treated with particular sensitivity, whilst actively encouraging breastfeeding. Babies should be given the opportunity to breastfeed as often and for as long as they require. Early and unrestricted feeding encourages a good milk supply. Once breastfeeding is established the composition of breast milk changes during the feed from more watery low calorie foremilk to fat-rich higher calorie hind milk. Because of this it is important that one breast is emptied at each feed with the baby being offered the second breast afterwards if necessary. Breast engorgement may sometimes be caused by limiting feeds, which causes the baby to be hungry more frequently, thereby taking large amounts of foremilk only which is quickly replaced. The baby may fail to gain weight despite the mother appearing to have an adequate milk supply. (RCM 1991). Formula feeds should only be used in exceptional circumstances, and after discussion with the mother. Liaison with Paediatric staff will also usually be necessary in these circumstances. Babies who may require milk other than breast milk include: Babies who are ill. Babies who are small for gestational age. Pre term babies. Babies whose mothers are unable to feed them due to illness or mothers who are taking medication which may be contra-indicated in breast feeding. Breast milk should be expressed and stored or discarded in these circumstances, to ensure future milk supply. It is preferable that babies who require expressed breast milk or formula are given it by cup, spoon or tube feeding rather than a teat and bottle. The importance of night feeds Milk production continues through the night and night feeds provide a substantial amount of the baby's milk intake in a 24 hour period. Night feeds should be encouraged not only to stimulate the breasts but also to help the mother to practice breast feeding while her breasts are soft. As hospital stays are often short these days it will give the mother more opportunity to overcome any problems she may encounter while help is easily available. Expression of breast milk Mothers may need to be shown how to express their breast milk for the following reasons: To soften engorged breasts prior to attaching the baby. If her baby cannot breastfeed for any reason. If mother needs to return to work or leave her baby with someone else for a few hours. If her breasts are too full and uncomfortable. Breastmilk may be expressed by hand, by hand pump or electric pump. Mothers should be instructed on the importance of cleaning and/or sterilisation of all equipment used, particularly if the milk is to be stored and given to her baby later. Mothers should be given both written and verbal information on how to hand express their milk as well as how to operate a hand or electric pump. Some breast pumps are more effective on some women than others, and the mother should be advised to try a few different pumps if possible if she is going to purchase her own. 5 Mothers who need to express their breastmilk on a long term basis e.g. pre-term baby on Special Care Baby Unit, often need particular help and encouragement. They will need to express their milk 6-8 times a day, including at least once during the night, to maintain their milk supply. Storage of breast milk Breastmilk can be stored for up to 24 hours in the refrigerator, one week in the freezer compartment of the refrigerator and up to 3 months in the freezer. It should be stored in sterilised plastic airtight containers which should be labelled and dated and used in rotation. Breastmilk should be defrosted in the fridge and can be kept for up to 24 hours. If it is defrosted to room temperature it should be discarded if not used. Breastmilk should never be re-frozen. Some common problems which may occur when breast feeding Health Care Professionals should be regularly trained and updated on problem prevention and problem solving. Sore nipples As mentioned earlier it is common in the first days for mothers to experience a sharp pain in their nipple when the baby initially begins to feed. Reassurance should be given that this will fade after the first few sucks. Continued pain often indicates that the baby is incorrectly positioned. Advice should be given accordingly. A change in the way the baby is lying e.g to under the arm or across the knee may help to ensure that pressure is not put on the same part of the nipple every time. Breast milk may be gently rubbed into the nipples after feeds to aid the healing process. Frequent or prolonged feeding Realistic expectations of the length and/or frequency of feeds should be given to mothers both antenatally and when breast feeding is commenced. Many mothers worry that their baby is not getting enough milk and need reassurance and encouragement until lactation is established. Frequent feeding is to be expected and is desirable until lactation is established. Once lactation is established frequent or prolonged feeding may be a sign that the baby is not correctly positioned and is not receiving enough hind milk. Mothers should also be reassured that their babies may be going through a "growth spurt" when they will demand extra milk and that their breasts will quickly adjust to the increased demand. Many mothers will blame themselves for "not having enough milk" at this stage and this is a very common reason for giving up breast feeding. Extra reassurance and support is needed at this time. Engorged breasts Mothers whose babies are correctly positioned, and fed on demand, including night feeds, are much less likely to get engorged breasts (RCM 1991). The mothers feeding technique should be observed. It may be necessary to gently express milk to soften the breasts to enable the baby to latch onto the breast more effectively. A warm bath or shower may also help to encourage this. Mastitis Over distension of the alveoli in the breasts can activate the mothers immune system causing non infective mastitis, characterised by a red painful area on the breast, a flu-like feeling and a rise in the mothers temperature. Antibiotics are not necessarily required at this stage. However this can lead to infective mastitis which needs to be treated promptly to avoid abscess formation. Mastitis is not a reason to cease breast feeding, indeed further engorgement may well exacerbate the problem (RCM 1991). Post partum care of the breastfeeding mother and baby On-going help is available from: Midwives. Health Visitors. UK Baby Friendly Initiative 20 Guildford Street, London, WCIN IDZ 6 UNICEF Room BFI, FREEPOST Chelmsford, CM2 8BR National Childbirth Trust, Alexandra House, Oldham Terrace, Acton, London W3 6NH. La Leche League, BM 3424 London WC1N 3XX. Association of Breastfeeding Mothers, P0 Box 441, St Albans AL4 OAF References and other useful reading Successful Breastfeeding (1991) ROM, London. Churchill Livingstone Hypoglycaemia of the Newborn (1997) National Childbirth Trust. Copies available from NCT Maternity Sales Ltd., 239 Shawbridge Street, Glasgow G43 1 QN Drugs in Breast Milk: A compendium (1996) National Childbirth Trust, George Over, Rugby. 7 Postnatal depression Research shows postnatal depression (PND) to be a relatively common problem often missed by health professionals which if undiagnosed can lead to greater problems in the future (Atkinson & Richel 1994, Cox 1989, Seeley 1996) As part of the audit cycle started in December 1996 we set ourselves a task of establishing a practice protocol to make sure that all professionals in the PHCT are working towards the same standards of care. We felt it was important that the whole PHCT was involved and committed to the idea of identification of PND. Following the completion of the audit cycle started on Dec 1st 1998 a full protocol will be drawn up involving other professionals. Antenatal It is planned to introduce the topic of PND at the Health Visitors first contact with the mother-to-be. This may be at the early bird session at about 20 weeks, at parentcraft sessions and/or the home visit at 3036 weeks. During this antenatal period the HVs will be working with the midwives when discussing: experiences and images of motherhood regarding realistic parenting encouraging supportive relationship education about postnatal disorder introduction of EPDS as a tool for the early identification of PND. It shows women that I-IVs are interested in them and their well being not just the baby, and enables them to raise other topics not otherwise discussed promoting continuity of care important Home Visit HV to visit mother antenatally at home 30 -36 weeks introduction of EPDS (or reiteration for those who have attended parentcraft) extra support visits if identified risk assessment This preparatory work in the antenatal period is followed up at the primary visit or during the visits in the first 6 weeks. One of the HV aims will be to create a time which is mother-centred when the mother can talk about her own physical, emotional, psychological and social health 5-6 weeks postnatal At a home visit 5-6 weeks postnatally the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale will be given to the mother for her to complete. The score will be recorded on the sheet itself and a summary sheet kept by the HV. The score is discussed by the mother and for HV intervention See flow chart 10-16 weeks postnatal 8 EPDS will be repeated in the Child Health Clinic or at home. The score will be discussed with the mother and health visitor intervention as recommended in the flow chart 20-26 weeks postnatal 20-26 weeks postnatal HV will only use the scale opportunistically Question 10 self harm - if score 1-3 some follow up to discuss in more depth the woman's response. If there are concerns the GP to be informed especially if over a weekend. Antenatal visit Discuss the realities of parenthood including the possibility of postnatal depression Explain the role of the HV and the EPDS Give PND handout, your telephone number and contact times First postnatal visit Demonstrate interest in her emotional response to the birth experience and to motherhood Give info about EPDS, your telephone number and contact times 5-6 WEEKS: EPDS 1 ALL MOTHERS Home Under 12 No action required 12 + discuss; if depressed offer a set number of weekly visits. Repeat EPDS after 2 wks Inform GP 10-16 WEEKS: EPDS 2 ALL MOTHERS Home or clinic Under 12 No action required 12+ for 1st time: Discuss: if depressed offer set number of visits Inform GP 12+ after minimum of 4 extra visits Inform GP consider referral 20-26 WEEKS: EPDS 3 Opportunistically Home or clinic Under 12 No action required 12+ for !st time: Discuss: if depressed offer set number of visits Inform GP 12+ after minimum of 4 extra visits Inform GP consider referral EPDS is only a tool and is only as good as the people who use it. It should never override professional judgement References Atkinson A and Richel A (1984) Post partum depression in primiparous parents J of Abnormal Psychology 93 12 1-130 Cox J (1989) Can postnatal depression be prevented? Midwife Health Visitor and Community Nurse 25 8 326-9 Seeley S, Murray L, Cooper P, (1996) The outcome for mothers and babies of health visitor intervention Health Visitor 69 4 135-138 9 Today’s date………………………………… ID ………………………………… EDINBURGH POSTNATAL DEPRESSION SCALE (J L Cox, J M Holden & R Sagovsky)* Health Visitor Number Maternal Age Baby’s Age Baby’s date of birth Gestational age Birth weight Feeding Triplets/twins/single Male/female HOW ARE YOU FEELING? As you have recently had a baby, we would like to know how you are feeling now. Please underline the answer which comes closest to how you have felt in the past 7 days, not just how you feel today. Here is an example already completed: I have felt happy: Yes, most of the time Yes, some of the time No, not very often No, not at all This would mean: “I have felt happy some of the time” during the past week. Please complete the other questions in the same way. IN THE PAST SEVEN DAYS 1. I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things: As much as I always could Not quite so much now Definitely not so much now Not at all 2. I have looked forward with enjoyment to things: As much as I ever did Rather less than I used to Definitely less than I used to Hardly at all 10 3. I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong: Yes, most of the time Yes, some of the time No, not very often No, not at all 4. I have felt worried and anxious for no very good reason: No, not at all Hardly ever Yes, sometimes Yes, very often 5. I have felt scared or panicky for no very good reason: Yes, quite a lot Yes, sometimes No, not much No, not at all 6. Things have been getting on top of me: Yes, most of the time I haven’t been able to cope at all Yes, sometimes I haven’t been coping as well as usual No, most of the time I have coped quite well No, I have been coping as well as ever 7. I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping: Yes, most of the time Yes, some of the time No, not very often No, not at all 8. I have felt sad or miserable: Yes, most of the time Yes, quite often Not very often No, not at all 9. I have been so unhappy that I have been crying: Yes, most of the time Yes, quite often Only occasionally No, never 10. The thought of harming myself has occurred to me: Yes, quite often Sometimes Hardly ever Never (*Detection of Postnatal Depression, Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, B J Psych.. 1987, 150, 782-786) EDINBURGH POSTNATAL DEPRESSION SCALE Name: Address: Baby’s age: As you have recently had a baby, we would like to know how you are feeling now. Please underline the answer which comes closest to how you have felt in the past 7 days, not just how you feel today. Here is an example already completed: I have felt happy: Yes, most of the time Yes, some of the time No, not very often No, not at all This would mean: “I have felt happy some of the time” during the past week. Please complete the other questions in the same way. IN THE PAST SEVEN DAYS 1. I have been able to laugh and see the funny side of things: As much as I always could Not quite so much now Definitely not so much now Not at all 2. I have looked forward with enjoyment to things: As much as I ever did Rather less than I used to Definitely less than I used to Hardly at all 3. I have blamed myself unnecessarily when things went wrong: Yes, most of the time Yes, some of the time No, not very often No, not at all 4. I have felt worried and anxious for no very good reason: No, not at all Hardly ever Yes, sometimes Yes, very often 2 5. I have felt scared or panicky for no very good reason: Yes, quite a lot Yes, sometimes No, not much No, not at all 6. Things have been getting on top of me: Yes, most of the time I haven’t been able to cope at all Yes, sometimes I haven’t been coping as well as usual No, most of the time I have coped quite well No, I have been coping as well as ever 7. I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping: Yes, most of the time Yes, some of the time No, not very often No, not at all 8. I have felt sad or miserable: Yes, most of the time Yes, quite often Not very often No, not at all 9. I have been so unhappy that I have been crying: Yes, most of the time Yes, quite often Only occasionally No, never 10. The thought of harming myself has occurred to me: Yes, quite often Sometimes Hardly ever Never 3 GESTATIONAL DIABETES Affects 2-4% of pregnancies Screening r more glycosuria at booking and 28 weeks Diagnosis Management B PRE-EXISTING DIABETES Delivery: -40 weeks if good diabetic control, earlier if complications and fetus Postnatal: feeding B Specialist Team nic with specialist team C A SIGN Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy A Quick Reference Guide Derived from the National Clinical Guideline recommended for use in Scotland by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network A B C refers to grade of recommendation B B B % TO 1% B IDDM - Occurs in c. 3.5/1000 pregnancies Contraceptive advice and pre-pregnancy care easures to improve outcome During pregnancy: -hour access to the specialist team and regular assessment - avoid hypoglycaemia and ketoacidosis isk NIDDM REDUCES HIGH PERINATAL MORTALITY 4