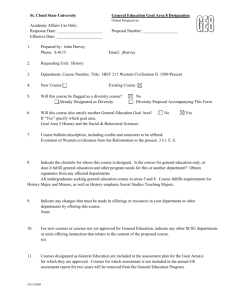

World Civilizations Outline - Channel View School For Research

advertisement