PITFALLS TO AVOID IN VETERINARY DERMATOLOGY

advertisement

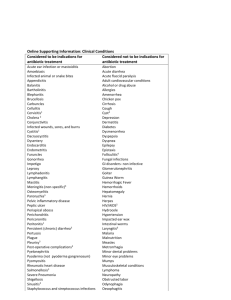

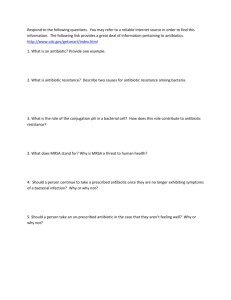

PITFALLS TO AVOID IN VETERINARY DERMATOLOGY Tiffany Tapp, DVM, DACVD Veterinary Healing Arts, Inc. East Greenwich, RI INTRODUCTION Practicing the art of medicine is a time-honored cliché. There is no one correct way of practicing and many routes often lead to the same final destination. Given the fact that most dermatological diseases are chronic, though not often fatal, this often allows for many side paths of “trial and error” by the clinician. Thus dermatology lends itself, more than most disciplines, to this form of practice. Along the way there are often judgment calls and assumptions made that in the long run are not always correct. This lecture will focus on several areas in which problems sometimes occur. These are areas in which veterinary dermatologists commonly see problems in working up dermatology cases that ultimately are referred to us. 1. HISTOPATHOLOGY – Pitfall: Performing biopsies too late in the course of the disease or biopsying lesions not likely to give an accurate diagnosis. Biopsies and histopathologic interpretations can often be an invaluable tool in helping to establish definitive diagnoses or disease categories. Many times practitioners get frustrated with results when they do not diagnose specific disease entities; but in reality eliminating many diseases can be just as helpful. Some of the ways in which histopathology can be helpful include showing evidence of multiple diseases, helping to establish treatment protocols and helping to diagnose serious life threatening disease. In addition, some diseases require histopathology for diagnosis. Biopsies are also indicated when there is a lack of response to what is perceived to be appropriate therapy. Site selection to determine areas to biopsy is really partly an art, but there are multiple guidelines to follow which can be helpful in assuring that biopsied areas are more likely to be diagnostic for specific diseases. Biopsying multiple sites or a continuum of the disease can be extremely helpful in establishing how a disease is progressing. It is also important to biopsy lesions early in the course of the disease. You are much more likely to find diagnostic changes in an early lesion than one that is older, scarred, or crusted. The clinician should also pick lesions that are needed for the diagnosis of the suspected disease. This requires the clinician to have some knowledge of the disease, which he or she is actually looking for. For example, if we are looking for a diagnosis of pemphigus we know biopsying pustules would be more helpful in establishing that particular diagnosis. If we were looking for lupus we might want to biopsy areas that have vesicles, blisters, erosions or ulcerations. If we were looking for a diagnosis of allergic skin disease we would want to biopsy areas with inflammatory changes, papular eruptions or erythema. “Honey” – 9 year old FS Golden Retriever History: 5-month history of scaling, hair loss and erythema and a 1 month history of nodules around the eyes, mouth and vulva. No response to 3-week course with appropriate dose of oral cephalexin. Clinical exam: Erythema to ventrum, distal extremities, and pinnae with patchy areas of hair loss on limbs and alopecia of pinnae. Mild to moderate scaling. Hemorrhage and intense hyperemia in the mucous membranes of the mouth and crusting at commissures of mouth. Alopecia and erythema with scaling on muzzle. Enlarged vulva with nodular swelling on right side and erythema and erosions on surface. Hints: No history of skin disease until recently. Non-pruritic. Erythema, scale, alopecia, and scattered hemorrhages and nodules. Diagnosis: Biopsies revealed mycosis fungoides (T-cell lymphoma) 1 2. SKIN SCRAPING – Pitfall: Not performing skin scrapings or misinterpreting the results. Skin scraping is one of the most frequently used tests in veterinary dermatology and is recommended anytime the differential diagnosis includes microscopic ectoparasitic diseases. It is important to realize that, although testing may accurately confirm diseases, its sensitivity for ruling out a diagnosis depends on the disease and the aggressiveness of sampling. Skin scraping is most commonly used to verify or rule out the diagnosis of demodectic mange. It is also commonly used to try to establish the diagnosis of sarcoptic mange, cheyletiella infestations and other ectoparasitic diseases, although it does not effectively rule out these diagnoses. Not all skin scrapings are made in the same way. The method of scraping for demodectic mites is different from that of scraping for sarcoptic mites. No matter which type of scraping is made, a consistent orderly examination of the collected material should be done until a diagnosis is made, or all the collected material has been examined. Demodectic mites Generally multiple scrapings from new lesions should be obtained. The affected skin should be squeezed to extrude the mites from the hair follicles. It is helpful to apply a drop of mineral oil to the skin site being scraped or to the scalpel blade to facilitate the adherence of material to the blade. Then additional material is obtained by scraping the skin more deeply until capillary bleeding is produced. It is important that true capillary bleeding is obtained and not blood from lacerations or cuts. It seems that skin scraping is a straight forward, easy laboratory procedure however, the author commonly encounters referred demodicosis cases in which false negative skin scraping findings led to misdiagnosis, or skin scrapings were not performed. Skin scrapings are advised in most cases of canine pyoderma and scaling, and follicular disorders because generalized demodicosis may be the primary disease. While I do disagree with some dermatologists who say that every dog needs to be scraped, there are certain instances in which skin scrapings are critical. Skin scrapings are required in: 1. Dogs under 12 months of age 2. Older dogs with no history of skin disease 3. Any dog with a recent or chronic history of steroid use Scabies Mites Canine sarcoptic mites reside within the superficial epidermis. However, because small numbers of mites are usually present, they are difficult to find. Multiple superficial scrapings are indicated with emphasis on the pinnal margins and elbows. The more scrapings are performed, the more likely a diagnosis. However, even with numerous scrapings, scabies cannot be ruled out because of negative results. Skin scrapings are required in: 1. Any chronically, poorly responsive pruritic dog 2. Any case where owners are also pruritic “Rex” 10-year-old MN Golden Retriever History: 4 month history progressive hair loss, redness, odor, scaling. Clinical exam: Alopecia on paws and face with erythema, fine tightly adherent scaling, pigmentation. Skin is friable and bleeds easily when samples taken. Test results: Cytology shows cocci from affected areas and a skin scraping is positive for adult and juvenile demodex mites. Bloodwork to check for underlying disease showed elevated lymphocyte count and toxic lymphocytes. O’ does not want to pursue additional testing. Treatment: Ivermectin 500 ug/kg EOD orally. Oral Cephalexin dispensed until recheck appointment at 1 month. Topical bathing with SulfOxydex shampoo every 1 to 2 weeks as o’ is able to. This is a current case so follow-up unknown. Over half of the cases of adult-onset generalized demodicosis have an underlying disease. 2 “Cajun” 3 year old neutered male Pug History: 1-year history of pruritus initially partially responsive to steroids. Has continued to worsen with hair loss, papular rash. No longer responds to steroids. Tentatively diagnosed as allergies. Other dog in house is slightly itchy. O’ initially reports that he is not itchy but when he questions other family members, wife reports recent rash on her arms. Cajun was previously treated once with ivermectin for possible scabies with no change in clinical signs. Skin scrapings in past have been negative. Clinical exam: Generalized thinning of coat with patchy alopecia, papular rash, and erythema. Hints: Poor response to steroids, owner also has rash. Diagnosis: Scabies. Skin scraping: negative. Treated ALL dogs in household with ivermectin (250 ug/kg SQ weekly for 3 weeks) and all signs disappeared within 3 weeks. Note: in past, only Cajun had been treated and other dog served to reinfect him! 3. CORTICOSTEROIDS – Pitfall: Overuse of steroids While the advent of corticosteroids provided a great service to the human and veterinary communities, their use (or misuse) has been a tremendous problem. Glucocorticoids have potent effects on the skin and profoundly affect immunologic and inflammatory activities. Glucocorticoid response to inflammatory stimuli is non-specific i.e. it is the same whether it is a response to infection, trauma, toxin or immune mediated. This is in fact the cause for much misinterpretation and confusion, since almost any disease will show partial and temporary response to glucocorticoids. It is imperative to know, or at least have a working differential, in order not to do more harm than good with their usage. Diseases such as autoimmune diseases (pemphigus, lupus, etc), sterile nodular diseases and juvenile cellulitis would be diseases in which steroids are indicated. Some forms of keratinization defects and some allergic skin diseases (seasonal atopy) are diseases in which steroids are acceptable while bacterial pyoderma, malassezia, and scabies would be diseases in which steroids are contraindicated or of minimal use. Since many of these diseases can occur on the same patient appropriate diagnostics, not presumptive or knee jerk reactions, are critical. I would suggest several guidelines or contraindications for steroid use. 1. The first and most important contraindication is the presence of pyoderma or malassezia. Bacterial infections are quite common secondary diseases to a number of primary diseases. The clinical evidence of a pyoderma can be varied; however, generally papular, pustular eruptions, scale or crusting is noted. The client often complains of an increased odor or bad smell. These are all clinical signs that should make the clinician suspicious of a secondary bacterial pyoderma. Cytological evidence is also helpful in establishing the presence of a pyoderma or malassezia infection. In the presence of a pyoderma it is always contraindicated to use glucocorticoids until the pyoderma or the malassezia disease is controlled. The use of corticosteroids can often make it difficult, if not impossible, to control the underlying pyoderma. The author sees many patients in whom combinations of antibiotics and glucocorticoids are used at the same time and results in an unsatisfactory control of the underlying pyoderma, continued pruritus and a frustrated client. 2. Long-term usage should be avoided. Long-term therapy is associated with many more side effects, and particularly side effects leading to poor health or disease. Of major concern is the increased risk of infections. A variety of bacterial infections may be seen but the most common are bladder infections, skin infections, generalized septicemia, and respiratory infections. Generalized demodicosis or malassezia dermatitis may also occur as a result of the immune suppressive effects of the corticosteroids. In more susceptible dogs or dogs receiving higher dosages, alopecia, thin skin, calcinosis cutis, atrophic remodeling of scars, milia-like comedones, and follicular cysts may occur alone or in combination. Musculoskeletal abnormalities that occur may go unrecognized as glucocorticoid side effects. The alteration in metabolism may lead to hyperlipidemia and steroid hepatopathy. Endocrine changes induced may include adrenal gland suppression then atrophy, diabetes mellitus, decreased thyroid hormone synthesis and increased parathyroid hormone levels. 3. Attempt to use low alternate day dosages. The previously discussed side effects are not eliminated by using low alternate day dosages, but many of them can be better controlled or avoided with this schedule. 3 4. Choose the correct glucocorticoid. The choice of the glucocorticoid may be difficult. A clinician cannot establish a single rule or set of rules that apply to all patients with a given glucocorticoid responsive dermatosis. In long term therapy the risk of injectable glucocorticoids overrides any other concerns. The clinician learns, often by personal experience, that some glucocorticoids do not seem to work as well as others. In certain patients however; the claim that injectable glucocorticoids are needed in some cases and that oral glucocorticoids are not effective is rarely accurate. In the majority of these cases ineffective oral dosages were used or tapered too quickly. A common mistake is to give an injection then go immediately to a low alternate day oral dose. In addition, the clinician may discover that a patient can receive certain glucocorticoids without significant adverse effects but not others. Hence, a dog may develop colitis or behavioral changes with prednisone but not with dexamethasone or triamcinolone. “Clancy” – 4-year-old male neutered mixed breed History: Presented with a two-year history of “scaly patches and hair loss”. Overall the dog was nonpruritic, had had no response to fatty acids and multiple steroid injections. Fungal culture was negative and the dog had been on and off antibiotics for 5-10 days, used concurrently with steroids. Injections received: 4/14: Vetalog 4/25: DepoMedrol 5/26: DepoMedrol 6/14: Vetalog 7/13: DepoMedrol 8/13: DepoMedrol 8/22: DepoMedrol 9/1: Vetalog 9/22: DepoMedrol 10/12: DepoMedrol Clinical exam: Multifocal 1-2 cm circular scaly crusted areas with purulent debris, focal alopecia, scale, epidermal collarettes with mild erythema. Numerous comedones and hyperpigmented circular lesions on ventrum. Cytology: large number of neutrophils with intra and extracellular cocci. ACTH stimulation test: pre-cortisol level - .1; post-cortisol level - .3. Treatment: Cephalexin 10 mg/lb BID x 5 weeks Diagnosis: Bacterial infection; immune suppression from overuse of corticosteroids. This is an extreme situation, but I see many dogs referred that have pyoderma and are ultimately just that but cannot be resolved because of the administration of concurrent corticosteroids. It is important to educate clients that the anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids may mask the pyoderma; making the resolution of the infection impossible. “Baylee” – 3 year old spayed female Vizsla History: 2 year history of seasonal pruritus. Has been seen previously here and allergy tested. Was doing well on antigen injections and occasional treatment with antihistamines. However, owner reported recent onset of pruritus in the axillary and inguinal region. The owner admitted to selftreating the areas with her own steroid cream for the past 3 weeks with no improvement. Clinical exam: Skin in axillary region is lichenified and scaly with underlying erythema. Skin in inguinal region appears thin and tissue paper like with some superficial scaling. Numerous comedones in axillary region. Cytology: numerous intracellular cocci within neutrophils Diagnosis: steroid atrophy with secondary pyoderma Treatment: discontinue topical steroid and institute oral antibiotic therapy with Cephalexin for 3 weeks Complete resolution of lesions occurred. 4 4. ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY – Pitfall: Various inappropriate uses. The basic and most important principles of successful systemic antibiotic therapy for the management of canine pyoderma include: choice of the proper antibiotics, establishment of an effective dose and adequate maintenance of therapy to insure cure rather than simply transient remission. Antibiotics can either be selected empirically or based on the results of bacterial culture identification and sensitivity testing. An antibiotic chosen empirically should have a known spectrum of activity against Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, the most common canine cutaneous pathogen. Cytology from a pustule or fistulous tract may be performed to verify the suspicion that infection is caused by gram-positive cocci. A culture should be considered if organisms other than cocci are observed on cytology or if resistant bacteria are suspected. If a single oral antibiotic will not cover multiple isolates an appropriate antibiotic that is effective against the isolated Staph intermedius should be chosen initially because this organism creates a tissue environment favorable to the replication of other secondary bacterial invaders. Perfusion of skin is less then ideal for establishing adequate dosages of antibiotics in comparison to other body tissues. According to some studies only 4% of cardiac output reaches the skin, in contrast to 33% of cardiac output reaching muscles and even higher levels to other body organs. In addition, tissue levels of some antibiotics reach only marginal levels in the subcutis and even lower in dermal/epidermal junction. Sequestered foci of infection, foreign body granulomatous response and antibiotics inactivation by inflammatory products further compromise effective antibiotic dosing in dogs with deep pyodermas. The establishment of appropriate antibiotic dosages is controversial. Dosages used should be as close to established recommendations as possible but should not be less than recommended. Some authors have stated that in general, doses of antimicrobial agents are doubled for skin infections so that effective tissue concentrations are more likely to be achieved. Although there is not general acceptance of this view, it does illustrate that dermatologists are not unwilling to increase dosages in patients with skin infections. Higher than established antibiotic dosages are often necessary in dogs with deep pyoderma as sequestered foci of infection may be protected by granulomatous inflammation. When treating deep pyoderma with excessive scarring and sequestered infection, the author has successfully used cephalexin at higher dosages than recommended. Adverse side effects are generally uncommon. Antibiotic therapy must be maintained until complete elimination of bacterial infection, rather than simply transient remission is achieved. This usually necessitates a minimum of 3 weeks for superficial pyodermas and sometimes as long as 10-12 weeks for deeper pyodermas. Antibiotics are rarely used in veterinary dermatology in accordance with manufacturer’s recommendations of duration of therapy. The suggested duration of therapy listed by most manufacturers fall far short of the time span actually required to insure cure for most types of canine pyoderma. Multiple studies have documented sensitivity and resistant patterns of Staphylococcus intermedius. Penicillin, ampicillin, amoxicillin and tetracycline are poor choices for the management of canine staphylococcal pyoderma. The sensitivity of most Staphylococcus intermedius isolates shows a very low susceptibility to these antibiotics. Clinical trials and sensitivity testing have demonstrated that a wide range of different antibiotics is effective in managing various types of canine pyoderma. Erythromycin, lincomycin, clindamycin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim and ormetoprim sulfonamides, oxacillin, cephalexin, cephadroxil, enrofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, clavulanic acid potentiated amoxicillin and rifampin all have their fans and opponents. The most important factor is to match the antibiotic’s spectrum of activity vs. the types of organisms that are seen cytologically (or preferentially in the case of rod shaped bacteria via culture and sensitivity testing). Another pitfall to avoid is the lack of identification of underlying diseases or circumstances that contribute to pyoderma. Problems commonly complicating management in this manner include underlying pruritic disease, disease altering the structure or function of the hair follicle, chronic cutaneous inflammation and diseases that diminish immune surveillance against bacterial invasions such as endogenous or iatrogenic hyperadrenocorticism and hypothyroidism. MRSA What is MRSA? MRSA stands for methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus. This resistant bacteria carries the mecA gene, which is carried on staphylococcal chromosomal cassette (SCC). The mecA gene can be shared among Staph. MRSA is an important nosocomial infection in human medicine. Staph aureus was first identified in the 1880’s. If we are then to follow the MRSA timeline: 5 1928 Alexander Fleming discovers the first antibiotic, penicillin 1941 Penicillin available in the US and England 1942 Penicillin-resistant staph aureus reported 1959: Methicillin introduced 1961: Doctors find first cases of MRSA (England) 1968: First report of MRSA in USA (Boston) 1974: MRSA accounts for 2% of hospital staph infections 1981: First community acquired (CA) MRSA reported 1997: MRSA accounts for 50% of hospital staph infections 2007: CDC estimates MRSA causes 94,000 severe infections yearly with 19,000 deaths 2006 and 2008 veterinary studies show 10% of equine personnel colonized Veterinary dermatologists/staff 2.33% more likely to be colonized than general population Antech reports the numbers of MRSA are up each year since 2005. Of Staph infections in general practice: Staph pseudintermedius 73% Staph Schleiferi 19% Staph aureus 5% 12% methicillin resistance Specialty/referral: 30% resistance So what do we do with all this information? Recognize the fact that methicillin resistant staph is an emerging pathogen. Remember most veterinary isolates are still not staph aureus; we see s. pseudintermedius, s. schleiferi. At this time, they are not considered zoonotic. However since the mecA gene could move from one staph species to another theoretically, use precautions and wash hands frequently and use hand alcohol gels. Wash your lab coat daily; clean your stethoscope. Avoid ties. Clean exam rooms, waiting rooms between patients. Red flag cases which grow methicillin resistant staph. Culture suspicious cases sooner. When discussing MRS with owners, remind them to wear gloves when cleaning wounds, changing dressings. Remind them to frequently wash hands. Have them wash animal bedding, food bowls and disinfect hard surfaces. The author is culturing much earlier in suspicious cases. There are still a number of antibiotics that the methicillin resistant staph are still sensitive to and these include: Trimethoprim/ormetoprim sulfa Chloramphenicol Clindamycin Tetracycline Amikacin However the culture is necessary to identify the best antibiotic in each case as they can vary on a case by case basis. 5. HISTORY: The Pitfall: not obtaining a thorough history In my opinion, good history taking is without a doubt the most important aspect of a dermatology workup. There is absolutely no substitute for the information that clients have to offer. Many clients can give answers to questions that in fact most veterinarians could not answer about their own pets. Most dermatology practices have in-depth detailed history taking sheets and mine requires approximately 15 minutes to fill out. By reading the answers to this questionnaire, in about 75% of my cases, I have a good idea of what is happening before I walk into the room. While I am sure that most of you don’t have the luxury of excessive time to spend with clients, the more information that you obtain the more precise you can be and the more exacting your diagnostic plan can be. There are a number of questions that you should ask initially in any dermatologic case. The answers to these questions will not give you an exact diagnosis but will point you in the correct direction. Once a general direction is obtained, then more specific questions relating to that disease category can be asked. 6 For example, if an allergic dermatitis is suspected, questions that could be helpful include: (1) Is the animal pruritic? (2) If so, where? (3) Is the pruritus seasonal or non-seasonal? (4) Is there a history of skin problems? (5) What is the response to previous medication? CASES “Pearl” 8 year old FS Catahoula History: Sudden onset of pain and pruritus on the ear margins and bridge of nose. Pearl is an indoor/outdoor dog that was recently adopted from a rescue group. She has no previous history of skin disease. Signs seemed to appear “overnight” according to the owner. Physical Exam: Erythema, papules, crusting, and hemorrhage on bridge of nose and pinnae. The affected area is painful and pruritic. DDx: parasitic, eosinophilic furunculosis, Staph nasal folliculitis and furunculosis, dermatophytosis. Diagnostic Testing: skin scraping – negative; cytology – numerous eosinophils Diagnosis: Eosinophilic furunculosis Associated with insect bites and stings, occurs with acute onset. Treatment: systemic glucocorticoids (prednisone 1-2 mg/kg q 24 hours x 4 days then alternate day for 10 days) Prognosis: excellent Clue in history: sudden onset, new environment, location and intense pruritus, owner unaware of dog’s sensitivity “Freckles” 10 year old FS Cocker Spaniel History: No history of skin disease until the last 9 months. Owner noticed an increased smell with rash. Pruritic, mostly to the feet and neck. Antibiotics improved the smell and rash but relapsed quickly when discontinued. Hints: No history of skin problems until 10 years of age. Pruritus to feet and neck. Owner noticed a smell and antibiotics helped. Examination: Erythema, follicular casting, adherent scale and yellow crust to paws and neck. Diagnosis: Skin scrape revealed large numbers of demodex mites of all stages. A secondary pododermatitis was also present. Adult onset demodicosis (remember to look for underlying causes). This is a good case to illustrate 2 points. Good history taking would lead you to suspect something other than allergies. Always skin scrape older dogs with no history of skin disease. *Freckles was subsequently diagnosed with Cushing’s Disease. 6. INFECTIOUS OTITIS – Pitfall: Not performing cytology in house. Diseases affecting the ear account for 10-20% of the canine cases seen in small animal practices. Ear disease is generally a sign of other primary problems and many otic manifestations are part of concurrent generalized skin conditions. Finding the underlying cause of the ear disease can aid the clinician in developing a better treatment plan and better long-term control of otitis. The practitioner should obtain a detailed history of the case and perform very thorough physical and dermatologic examinations. Cytology is an invaluable tool in determining the primary etiologic agent of ear disease in small animals. This is easily obtained by using cotton swabs streaked upon a slide and then stained with a modified Wright’s stain or Diff-Quik stain. This is a very quick and easy method for rapidly staining specimens. It can also give you an insight into the appropriate topical or systemic therapy that can be used to help control the ear disease itself. Cultures and sensitivities are often performed with cytology to determine what specific organism is present, as well as determining what antibacterials could be most helpful in resolving the otitis. However they are often not needed in early cases of otitis. Cytology has the benefit over cultures of helping to quantitate the numbers and types of organisms. A culture may be overgrown by a dominant organism and it does not tell you the relative numbers of organisms in relation to each other. For instance, a culture may grow only Staphylococcus. However, cytology revealed both cocci and yeast organisms. By only treating the bacteria, one runs the risk of then developing an immediate yeast overgrowth due to the antibiotic therapy. Cytology also provides 7 immediate results and is very helpful during treatment of an otitis to assess response to treatment and outline further treatment protocols. Cultures and sensitivities should be considered when cytological impression smears reveal rod shaped organisms or when ear disease is not responding to what should be appropriate antibiotic therapy. Chronic recurrent otitis is the rule if underlying diseases are not controlled. We see many cases referred for chronic otitis that are responsive or partially responsive to therapy that quickly relapse once treatment has been discontinued. “Lily” - 2 year spayed female mixed breed dog History: 1.5 year history of chronic otitis unresponsive to Gentocin topically, and only partially responsive to Otomax. Relapses off of meds. Pruritus around head and ears primarily. Recently went to a second veterinarian for a second opinion and was told the only option was surgery. Owner visited our office for a confirmation before surgery. Clinical exam: Both ear canals and pinnae were inflamed and ears were filled with dark brown discharge. Dog was sensitive around head. Cytology: 4+ yeast AU Treatment: Cleaned ears under sedation. Treated with topical Conofite mixed with small amount of Dexamethasone twice daily. Due to chronic nature of problem and last medical treatment before surgery, also opted to treat with oral Ketoconazole for 2 weeks. Started dog on food trial to rule out food allergy. Ears cleaned by veterinarian at 2 week intervals because owner unable to clean at home. Diagnosis: Food allergy with secondary yeast otitis Update: Dog responded well to therapy and is now maintained on special diet and topical Conofite 12 times per week. Ears cleaned weekly with Malacetic Ultra ear cleaner. 7. FLEA CONTROL. The Pitfall: forgetting how powerful the flea is. Fleas are the most common external parasite of companion animals. Flea allergy dermatitis is the most common skin disease of both dogs and cats. Flea control remains a challenge for veterinarians and pet owners because the adult fleas cause the clinical signs but the majority of the flea population (eggs, larvae and pupae) live off the pet and in the house or area where the pets spend time. In the past, veterinarians could recite “the flea talk” as in their sleep. However in the late 90’s, newer flea control products came along and worked so well we saw a decline in flea problems, infestations and flea allergy. Veterinarians and pet owners became more complacent about treatment because the really severe cases became much less common. Pet owners became less educated which added to their compliance laxity. I am going to supply you with a brief review of flea biology since fully understanding it is key to successful management. Fleas are an obligate ectoparasite of their animal hosts and adult fleas can live only briefly off the host after taking their first blood meal. The adult flea will begin feeding almost immediately after finding a host. The females then begin laying eggs within 24 hours after they commence feeding. The eggs then fall into the environment where the pet spends time. They are susceptible to IGR’s for a period of time but not insecticides. The larvae then hatch and live in the environment. They are negatively phototactic and move horizontally over smooth surfaces to avoid light, heat, and desiccation. They can survive outside in shaded loose substrates such as leaves and other organic material. The larvae are susceptible to traditional insecticides as well as environmental IGR’s, including those shed in flea feces from the pet’s coat. Optimum conditions are 65 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit and high humidity. The pupae are encased within cocoons (often within carpet fibers or floor cracks). They are resistant to freezing, desiccation, insecticides and IGR’s. They can remain dormant for many months and are 8 stimulated to expupate by vibration, temperature and CO2. Once hatched, they will try to immediately find a host. The entire life cycle takes 14 to 140 days depending on conditions. Salivary proteins of the flea injected during the bite cause flea allergy dermatitis. A combination of Type I, delayed Type IV and cutaneous basophil hypersensitivity are all involved in producing the signs of flea allergy. There is no breed or sex predilection. Primary lesions are papules, which may be topped with small crusts. Self-inflicted secondary lesions are then seen including excoriations, alopecia, lichenification, scaling, crusting and fibropruritic nodules. Signs can vary in severity and tend to be progressive. Affected areas in the dog include the lumbosacral area, perineum, tail head, and caudal thighs. Pruritus tends to be predominantly localized to the caudal one-half of the dog. There are many flea control products on the market with different application methods (spot-on, topical spray, oral) and mechanisms of action. Some are FDA approved and therefore prescription only and others are EPA approved insecticides. As a veterinarian, we must help our owners decide what is the best flea control plan for them. The frequently bathed indoor only Bichon may have a completely different treatment from his neighbor, the rock-climbing, forest hiking Labrador. The goals of flea control should be to eliminate existing fleas on affected animals, continued elimination of fleas acquired from infested premises and prevention of reinfestation. Certainly one of the best ways to prevent reinfestation is to prevent fleas from laying eggs. By so doing, we stop the life cycle. Because female fleas begin laying eggs within 24 hours of feeding, we must use flea control products with a rapid kill so that adults are killed before they survive 24 hours. In addition, we must educate our clients to stay on top of treatment. Let’s take a common scenario: flea control product has 100% efficacy from day 1 to 21 and then efficacy starts to wane so by day 30, there is 97% efficacy. This allows 3% of the fleas to survive from greater than 24 hours and theoretically lay eggs which in turn will hatch into adults. When our clients apply or give products every 6 weeks or worse, our flea control treatment starts to fall apart and signs of flea allergy may appear again. Due to the summation of effect, an atopic Labrador with “OK flea control compliance” may go over the pruritic threshold when flea control wanes. It is important that we educate our clients so that they understand the significance of poor compliance. We can help them decide if a topical, an oral or a combination therapy is best for their pets. 9