New Light Baptists and the Founding of Rhode Island College

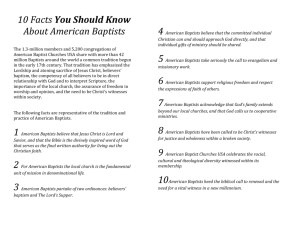

advertisement

1 Chapter 3 “Becoming Important in the Eye of the Civil Powers”: New Light Baptists, Cultural Respectability, and the Founding of the College of Rhode Island Thomas S. Kidd, Baylor University It may be hard for modern Americans, particularly Southerners, to fathom how countercultural eighteenth-century Baptists were. “New Light” Baptists emerging from the religious revivals of the mid-eighteenth century suffered significant persecution, especially under the governments of Connecticut and Massachusetts. The clerical and political establishments viewed Baptists as dangerous, destabilizing incendiaries who ordained untutored farmers and indulged spiritually extreme behavior. Baptists and other radical evangelicals claimed the indwelling of the Spirit, not credentials from Yale or Harvard, gave men (and sometimes women) the right to preach. Nevertheless, moderate leaders of the early Baptist movement did not disparage learning altogether, but instead sought to establish educational institutions to gain cultural respectability. In this context, the College of Rhode Island (later Brown University) was founded by Baptists in 1764. The founding of the College of Rhode Island raises critical questions about the place of education and the quest for cultural respectability in the anti-establishmentarian Baptist tradition. This essay will introduce the reader to the history of the eighteenth-century “New Light” Baptists in New England, focusing especially on the career of their most prominent leader, Isaac Backus. It will then consider decisions New England Baptists made regarding the maturation and 2 respectability of their movement, including the founding of the College of Rhode Island, ministerial associations, and their support for American independence. Finally, the essay will examine the connections between cultural respectability and the secularization of Brown, and conclude with reflections on the tension between respectability and public religious commitment at Baptist and Christian institutions of higher education. Baptists had been present in the American colonies from their founding, although Massachusetts had outlawed them in the 1640s. The Baptists achieved informal toleration in New England by the late seventeenth century. However, before the revivals of the 1740s, Baptists in America had little connection to the developing evangelical movement. All this changed when radical evangelicals began to promote a new primitivism and concern for the absolute purity of the church. Some former Congregationalists and paedobaptists began to wonder whether baptizing infants was not just a remaining corrupt practice not corrected by the Reformation. Reading their Bibles with newly critical eyes, Baptists realized that a plain reading gave little sanction for baptizing infants. Some Separates (those who had removed themselves, illegally, from the established churches of Connecticut or Massachusetts) began to see baptism simply as a public recognition of conversion. Baptizing only converted believers would clear up confusion regarding the status of infants: though believing parents would raise them in the church, children could not in any sense join the church until they showed hopeful signs that they had been converted. Isaac Backus, the key Baptist leader in eighteenth-century America and a future trustee of the College of Rhode Island, came over to these Baptist beliefs in a way that reveals the early movement’s anti-establishment characteristics. Backus was converted in 1741 in Norwich, 3 Connecticut, as part of the revivals of the “First Great Awakening.” Backus recalled “it pleased the Lord to cause a very general awakening Thro’ the Land; especially in Norwich.” He traced the operations of the Spirit in his soul to May and June of that year, when he saw “that now God was Come with the offers of his grace.” The arrival of itinerants greatly helped him along the conversion path: “It pleased The Lord to Send many Powerfull Preachers To Norwich,” including Eleazar Wheelock of Lebanon Crank and Jedidiah Mills of Ripton, Connecticut, soon thereafter. It was James Davenport of Southold, Long Island, whose preaching most deeply affected Backus, however: “About the begining of August Mr. Devenport Came to Norwich and preached There three days going in an exceeding Earnest and Powerful manner: and I apprehend that his labours were the most blest For my Conversion of any one mans.” Wheelock and Davenport cooperated in a number of “powerfull meetings” that August in Norwich. Backus, however, worried that despite the powerful work of the Spirit in Norwich, he would miss his opportunity to find grace. But on August 24, 1741, while “mowing in the field alone,” Backus finally apprehended the forgiveness available to him in Christ, saw that he too could be saved, and found that “now my Burden (that was so dreadful Heavey before) was gone.”1 In late 1744 Backus’s church began to squabble over the long-standing questions of ministerial associations recommended by Connecticut’s 1708 Saybrook Platform, and standards of full church membership. It is not clear whether the separation preceded or followed a relaxing of membership standards, but it does seem that Norwich’s pastor, Benjamin Lord, wanted both to deemphasize personal conversion testimonies for full membership and to continue an informal compliance with the Saybrook standards through his involvement with the New London County 1 William McLoughlin, ed., The Diary of Isaac Backus, vol. III: 1786-1806 (Providence, R. I., 1979), Appendix 1, 1523-26; William McLoughlin, Isaac Backus and the American Pietistic Tradition (Boston, 1967), 12-15. 4 Ministerial Association. By summer 1745, thirteen members, including Backus, had withdrawn from the church. Lord summoned them to explain their absence, and in August 1745, Lord recorded some of their reasons. Many expressed objections to Lord himself, saying he denied “the power of godliness” and was not sufficiently supportive of the late revivals. Some complained that the church had lax membership standards, and that it did not make “conversion a term of Communion.” Others protested that the church was committed to the congregational model of church government, but that Lord had swayed toward the Saybrook presbyterian model. One mentioned that Lord was no “friend to Lowly Preaching and Preachers,” and that he had banned radical Connecticut itinerant Andrew Croswell from preaching there. Mary Lathrop may have spoken for most when she stated simply, “By Covenant I am not held here any longer than I am edified.” The Separates established a new congregation in the western part of Norwich. The church appears to have benefited both from the radicals’ zeal and from the ongoing frustrations on the west side of town concerning the relatively distant location of Lord’s meetinghouse. In any case, the church ordained one of the Separates, Jedidiah Hide, as its first pastor in October 1747. Hide and Backus frequently itinerated together during this period. Hide testified that he separated from Lord’s church because “The Gospel [is] not preached here.”2 Backus later gave his primary reasons justifying church separations: 1) when “manifest unbelievers are indulged in the Church,” 2) when corrupt doctrine is preached, 3) when the true gospel and its messengers are shut out of the church, and 4) when the church admits to 2 J. M. Bumsted, “Revivalism and Separatism in New England: The First Society of Norwich, Connecticut, as a Case Study,” William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 24, no. 4 (Oct. 1967): 602-04, 607-08; Norwich Separates’ reasons for separation, in Frederic Denison, Notes of the Baptists, and Their Principles, in Norwich, Conn. (Norwich, 1857), 21-22, 24-26, reprinted in Richard Bushman, ed., The Great Awakening: Documents on the Revival of Religion, 1740-1745 (Chapel Hill, N. C., 1989), 102-03; McLoughlin, Diary of Isaac Backus, 1: 7 n.12. 5 membership those who “have the form of Godliness but [deny] the power thereof.” Backus cultivated a network of Separates that opponents would call the “Eastern Exhorters.” Among these was Joseph Snow, Jr., a Separate pastor in Providence, Rhode Island. In December 1747, Backus and Snow visited Titicut, a new parish in southeastern Massachusetts. Little did Backus know that this would become the place where he would serve the rest of his life, nor did he anticipate the controversies over baptism and church-state relations that he would soon generate. But as he sat down for dinner at his host family’s home, “’em words in John 4.35 to 38, were brought in With great clearness and power upon my Soul, and Thro’ ‘em Truths I was Led to View a Large field all white to harvest here. . .my hart was so drawn forth towards God, and in love to his People here that I felt willing to Impart not only the gospel to them But my own soul also, because they were made dear unto me; tho’ I knew none of ‘em personally. Thus the Lord bound me to this People ere I was aware of it.” Without seeking the approval of local ministers or officials, the evangelical inhabitants of Titicut asked Backus to stay and help them form a new church. Backus drew up a church covenant, which the new church members signed in February 1748.3 Backus had no college education, but those who joined the church believed his spiritual call to the ministry far outweighed his unfamiliarity with classical learning and languages. They were willing to court disdain and even persecution from educated elites for the right to ordain an uneducated but Spirit-filled minister who was committed to revivalism. The church arranged for 3 Isaac Backus, “Reasons of Separation” (1756?), in McLoughlin, Diary of Isaac Backus, 3: 1528; Samuel Finley to Joseph Bellamy, Sept. 20, 1745, Richard Webster transcription, Joseph Bellamy papers, Presbyterian Historical Society; McLoughlin, Diary of Isaac Backus, 1: 12; C. C. Goen, Revivalism and Separatism in New England, 17401800: Strict Congregationalists and Separate Baptists in the Great Awakening rev. ed. (Middletown, Conn., 1987), 217-28. 6 his ordination by inviting pastors and delegates from nearby Separate churches. To Solomon Paine of Canterbury they wrote, “the Lord hath appear’d Gloriously for us here. . .& he hath united our hearts in the Choice of our brother Isaac Backus to be our pastor.” Paine attended Backus’s ordination along with Jedidiah Hide, Joseph Snow, and other key Separates. As the ceremony began, a town official and several local ministers arrived and asked them to stop, but the Separates took no heed of them and proceeded to ordain Backus. The twenty-four-year-old Backus threw himself into the work of the church, and the original sixteen members had become sixty-one by the end of 1748. Members had to give convincing evidence of their conversion and practiced strict congregational rule. No halfway members were allowed.4 Backus and the Titicut Separates faced fines and occasional imprisonment for resisting tax payments to support the established churches in the area. Persecution would not remain as consuming an issue for Backus, however, in light of internal dissent in his church over the issue of baptism. In summer 1749, two church members began to proselytize for the doctrine of believer’s baptism, against the time-honored practice of infant baptism. Originally, Backus was stridently opposed to this innovation, as were most ministers across New England, whether Anglican, Presbyterian, or Congregational. Nevertheless, the question of Scriptural warrant for infant baptism began to haunt Backus and led him into the most profound spiritual crisis of his life after his conversion.5 To most Reformed Christians, rejecting infant baptism seemed both subversive and callous. It struck at the fabric of the social order, which required the passing on of the faith to each successive generation, and it seemed to abandon infant children to fend for themselves 4 Bridgewater and Middleborough Church to Canterbury Church, April 1, 1748, James Terry Collection, Connecticut Historical Society; McLoughlin, Diary of Isaac Backus, 1: 37-39; McLoughlin, Isaac Backus, 42-43. 5 McLoughlin, Diary of Isaac Backus, 1: 67 n.1. 7 outside the church. Baptists, of course, saw the matter much differently. They saw no clear call for infant baptism in Scripture, but saw plenty of evidence, particularly in the book of Acts, to suggest that baptism was for those who had put their faith in Christ for salvation. To them, the ritual was not a mark of entrance into the covenanted community, parallel to the Old Testament practice of circumcision. Instead, baptism was a symbol of the spiritual death and resurrection experienced in conversion. Most Separate churches, as well as established evangelical ministers like Jonathan Edwards, rejected the seventeenth-century Halfway Covenant that allowed baptized but unconverted parents to baptize their children. They saw this practice as a corrupt concession, allowing the unregenerate to share in one of the two most sacred privileges of church members (the other was the Lord’s Supper). Some Separates, however, took the abandonment of the Halfway Covenant one step further. They believed that baptizing unregenerate children meant the church would necessarily have unregenerate pseudo-members, so they adopted what they considered the apostolic mode of believer’s baptism.6 Backus must have wondered about these matters even before they became an open controversy in his church in August 1749. Otherwise, one could hardly conceive of his decision late that month to come out––temporarily––against infant baptism. He spent a great deal of time in prayer seeking direction about the matter, until suddenly he came to the conclusion that baptist principles must be right precisely “because I felt Such a Strugling against it.” Backus assumed if tradition strongly supported some theological notion, it was likely to be proved wrong by a plain reading of Scripture. Thus, on August 27, 1749 he told his congregation “that none had any right 6 Goen, Revivalism and Separatism, 208-09; Stanley Grenz, Isaac Backus--Puritan and Baptist (Macon, Ga., 1983), 70-71. 8 to baptism but Believers, and that plunging, Seemed the only right mode.” Even as he preached, however, Backus had second thoughts, and within a month his mind was “turned back to infant baptism.”7 Backus could not get away from believer’s baptism, however, and struggled with the question for the next two years. Finally, in July 1751 Backus announced to his church that he could find no grounding in Scripture for infant baptism. This was no easy decision, not only because of pressure against it from outside the church, but also because a majority of his church members were opposed to believer’s baptism. In August, Backus took a final step in his personal journey to baptist convictions by receiving believer’s baptism himself. Benjamin Pierce, a visiting Baptist pastor from Rhode Island, held a baptism service in Titicut at which Backus gave his conversion testimony and “went down Into the Water with him And was Baptized.” This move put many in his congregation into a “jumble,” he wrote.8 The “jumble” at Titicut persisted for months and a church council was called to try and address the “Unhappy Divisions” caused by “Isaac Backus his Travail in Baptism.” The church had almost ceased to function because of divisions over baptism, and Backus had stopped trying to enforce church discipline, even in flagrant cases. Backus could not agree to a proposed covenant renewal, and for a time left to go back to Norwich. He was recalled, however, to pastor the Titicut church under a mixed-communion plan, which accepted either infant or believer’s baptism for membership. This never worked very well, however, and the church staggered along in debilitating disagreement over the issue for five more years. 7 McLoughlin, Diary of Isaac Backus, 1: 68. 8 McLoughlin, Diary of Isaac Backus, 1: 143, 147-48. 9 The Separates and Baptists were very close to one another theologically, but their sharp disagreement over the meaning of baptism allowed no ultimate reconciliation. For instance, though he once entertained the idea of becoming a Baptist, Wethersfield’s Separate pastor Ebenezer Frothingham was calling believer’s baptism the “mystery of iniquity” by 1752. After many arguments and splits in local congregations, the Baptists and Separates finally held a synod in Stonington, Connecticut on May 29, 1754, to decide whether they could continue in mixed communion. Separate paedobaptists argued that either the paedobaptist “sins in making infants the subject of baptism,” or the antipaedobaptist sins “in cutting them off” from baptism. They recognized, probably correctly, that there was no point in trying to hold the two groups together, despite their common origins. In a key vote, the Separates at the synod carried a bare majority to close communion against Baptists. Backus continued to try and salvage a Separate-Baptist union, but to little avail. Finally, Backus decided in 1756 to make a final break with his church and start a Baptist church that would only accept believer’s baptism for membership. Once at Norwich and twice at Titicut, Backus helped engineer separations in the name of gospel purity. Considerations of cultural respectability seemed entirely irrelevant to the Baptists’ decisions to separate.9 Across the colonies, the Separate Baptists maintained an uneasy relationship with socalled Regular or Particular Baptists, who were generally receptive toward the revivals of the 1740s, but whose churches, and chief organizational structure, the Philadelphia Association (1707), predated the “Great Awakening.” The Regular Baptists’ denominational strength lay 9 Council at Bridgewater and Middleborough, Oct. 2, 1751, Ebenezer Frothingham to Solomon Paine, Nov. 23, 1752, James Terry Collection, Connecticut Historical Society; Goen, Revivalism and Separatism, 127-28, 219-21, 262-64; McLoughlin, Isaac Backus, 82-84; Isaac Backus, History of New England with Particular Reference to the Denomination of Christians Called Baptists (Newtown, Mass., 1871), 2: 113-15. 10 mostly in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, with a growing presence in the South. These Baptists, enjoying toleration in the Middle Colonies, were much more accomodationist in their cultural stance than their New England Separate counterparts. Accordingly, the Regular Baptists in the 1750s began to advocate establishing Baptist educational institutions that would lend intellectual credibility to the movement. The Hopewell (New Jersey) Academy was founded in 1756 for educating future Baptist pastors, and among its early graduates was James Manning, soon to become the first President of the College of Rhode Island.10 Manning himself attended the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), but the Philadelphia Association began to believe that the Baptists needed a college for themselves, an enterprise that no Baptists had yet taken on anywhere in the world. The idea was formally proposed in 1762. Though there was some initial thought of placing the college in the South, or in the Middle Colonies, it was determined that the institution would have the best chance for political and financial success in Rhode Island, a province with religious toleration, no existing college, and increasing Baptist strength. The idea for the “seminary of polite literature” was quickly welcomed by the Rhode Island legislature and by Newport’s Ezra Stiles, future president of Yale College. Stiles, a Congregationalist minister, tried to co-opt the plan for the college and create an interdenominational Christian school, but the Baptists insisted on maintaining a majority position on the trustee board and controlling the Presidency.11 From the outset, many Separate Baptists did not like the idea of a Baptist college and they did not appreciate the moderate Philadelphia Association horning in on the radical New England Baptist way. As we have seen, among the Separate Baptists’ hallmarks since the Great Awakening were an uneducated ministry and an accompanying suspicion of college education as 10 Reuben A. Guild, Early History of Brown University (Providence, R. I., 1897), 8-9. 11 Walter C. Bronson, The History of Brown University, 1764-1914 (Providence, R. I., 1914), 15-27. 11 a means to preserve the power of the establishment. It is too simplistic to call this sentiment “anti-intellectualism,” for the Separate Baptists always liked godly ideas and good (Calvinist) theology. They sorely resented, however, the way college graduates monopolized the statesupported ministry. Their grievance was held against the cultural hegemony exercised by the Congregational establishment, and one of the establishment’s chief claims to legitimacy was their education. The Separates of New England also, no doubt, felt a certain condescension coming from the more polite Philadelphia Regulars, who not only wanted to start a respectable college, but they wanted to start it in the Separates’ back yard. Backus expressed the concerns of many in a letter written to English Baptist John Gill shortly after the founding of the college. He noted that critics charged, “that none but ignorant and illiterate men have embraced the Baptist sentiments.” True enough, he acknowledged, as of the mid-1750s there were only two New England Baptist ministers who had college educations and neither of them were Calvinists (a requirement to be in good standing among the Separates). Backus told Gill that since the New England Baptists had “met with a great deal of abuse from those who are called learned men in our land, they have been not a little prejudiced against learning itself.”12 There is scattered evidence to suggest some Separate Baptists in New England opposed the college, or at least worried about what it might portend for the Baptist churches. Ezra Stiles wrote of one Baptist critic that “Eld[er] Young is Illiterate—don’t like the College—says when the old Ministers die off he forsees a new Succession of Scholar Ministers:––that it has got so far already as scarcely to do for a common Illiterate Minister to preach in the baptist meeting at Providence.” Critically, however, Isaac Backus threw his support behind the new college, even 12 Isaac Backus to John Gill, [1765?], in Guild, Early History, 64-65. 12 becoming a trustee. Backus decided in this case he would try the accomodationist approach, telling John Gill the lack of Baptist education might well be alleviated by the college, which “appears in a likely way to increase fast.”13 When Backus was elected as a trustee, one Baptist, Thomas Green, complained he could not understand how Backus, “acting faithfully, upon his own declared principles, can long keep his standing as a member of that body the chief of whose principles and views differing so widely from his.” Green speculated Backus might soon get kicked off the trustee board “for the truth’s sake.” Backus justified his cautious support for the college, however, by arguing that the Baptists needed leaders with college degrees, and that the Baptists could not safely send their boys to any other American college without fear that they would be recruited to another denomination. Some Baptist parents had been “disappointed” before as sons sent to Princeton, Yale, or Harvard had been drawn into Presbyterianism or Congregationalism. He argued that educational credentials were not foreign to the Baptist tradition anyway, so Rhode Island College could serve a godly purpose. Backus sternly warned, however, that he hoped Baptists “may never imagine to confine Christ or his church, to that, or any other human school for ministers.”14 In the school’s early years, James Manning won over many Separate Baptists by his management of the school. He continued to emphasize that true conversion was infinitely more important for ministers than good education. In 1769 he reminded graduates that they should make sure they “have been taught of God, before you attempt to teach godliness to others. To 13 Goen, Revivalism and Separatism, 276; Isaac Backus to John Gill, [1765?], in Guild, Early History, 64-65. 14 Goen, Revivalism and Separatism, 276; Isaac Backus, A Fish Caught in His Own Net (Boston, 1768), 129, in Guild, Early History, 65. 13 place in the professional chairs of our universities the most illiterate of mankind, would be an absurdity by far less glaring, than to call an unconverted man to exercise the ministerial function.” Soon Separates began widely to accept the legitimacy of the college, and Separate ministers participated in the ordination of early graduates.15 Soon after the chartering of the new college, supporters in Rhode Island became embroiled in a controversy over its location, a dispute that would ultimately result in the college’s settlement in Providence and its renaming for the wealthy Brown family, who lived there. In 1770, Providence and Newport emerged as the two leading contenders for the college’s location. Led by the merchants of the Brown family, Providence had raised almost £2700 in support for the college, but Newport’s boosters claimed to have raised just as much. Nicholas Brown wrote a letter to Backus pleading with him to support Providence. Providence’s boosters were more firmly committed to the college, and wanted it to remain distinctively Baptist, as opposed to its “New Friends” in Newport, according to Brown. At the corporation meeting, the supporters of Newport and Providence argued vehemently, with “such indecent heats and hard reflections as I never saw before among men of so much sense as they,” Backus wrote. When the vote came, Providence won by a slim majority. The decision favored a stronger Baptist identity over the more cosmopolitan and prosperous climes of Newport, but it also firmly committed the college to the financial support of the Brown family.16 The founding of the College of Rhode Island was quickly followed by the founding of the Warren Association (1767). Inspired by James Manning, this union of New England Baptist 15 Goen, Revivalism and Separatism, 276-77. 16 Nicholas Brown to Isaac Backus, Jan. 27, 1770, in Richard Luftglass, ed., “Nicholas Brown to Isaac Backus: On Bringing Rhode Island College to Providence,” Rhode Island History 44 (1985): 121-25; McLoughlin, Diary of Isaac Backus, 2: 753. 14 churches was clearly intended to imitate the structure of the Philadelphia Association. Many, including Backus, feared the new association would try to exercise authority over individual congregations, an issue toward which the persecuted Baptists felt particularly sensitive. However, the association made clear that it only meant to serve as an advisory council. Many Baptists saw the association as a central agency for agitating against the New England religious establishments. Accordingly, the Warren Association was successfully formed, and it adopted the Philadelphia (or Second London) Confession of Faith as its doctrinal standard. It affirmed Calvinist orthodoxy and believer’s baptism. By the early nineteenth century, even Separate Baptists had warmly embraced associations, with thirteen unions embracing more than three hundred churches in New England. By then, there was no point in referring to them as “Separates,” for disestablishment and growing sophistication made their antiestablishmentarianism passé.17 The culmination of the Baptists’ mainstreaming in New England, and American culture, came with their decision to support the cause of American independence from Britain. Backus began his campaign for the rights of religious dissenters in 1749 when he and other Separates protested against a local tax requiring Separates to help pay for a new Congregational meetinghouse. Their petition was rejected by the Massachusetts General Court. Backus suffered quietly under this taxation until the late 1760s, when he began publishing tracts advocating the end of the state-supported establishment. His key text on the subject was An Appeal to the Public for Religious Liberty, against the Oppressions of the Present Day (1773). In it, Backus argued that God clearly favored separate civil and ecclesiastical governments, in contrast to the frame of Massachusetts’ government. “Who can hear Christ declare, that his kingdom is, NOT OF THIS 17 Goen, Revivalism and Separatism, 277-82. 15 WORLD, and yet believe that this blending of church and state together can be pleasing to him?” Backus wondered. He cleverly linked the Baptists’ cause to the Patriots’, arguing that to deny the one while supporting the other was hypocritical. No American should expect that God “will turn the heart of our earthly sovereign to hear the pleas for liberty, of those who will not hear the cries of their fellow-subjects, under their oppressions.” The colonists complained of taxation without representation, yet “is it not really so with us?” Did not the Baptists have to support ecclesiastical governments in which they had no voice? The Baptists of Massachusetts arranged for a copy of An Appeal to the Public to be distributed to every member of the First Continental Congress.18 Backus decided to take his case directly to Congress, as little help seemed to be forthcoming from the Massachusetts legislature. Arriving in Philadelphia, Backus and his colleagues found themselves in over their heads in the city’s political waters. The Philadelphia Baptists were developing a reputation for Loyalism, keyed by pastor and historian Morgan Edwards’s promotion of the British side. Backus immediately met several Quaker leaders who were opposed to the Continental Congress. “These friends manifested a willingness to be helpful in our case,” but their assistance ultimately proved damaging. The Quakers advised Backus not to meet with the whole Congress, but with the Massachusetts delegates and others friendly to religious liberty. The meeting assembled on October 14, 1774, and included Samuel Adams, John Adams, and a number of other skeptical delegates. James Manning opened the session by reading a memorial of the Baptists’ grievances. John and Samuel Adams both responded with 18 William McLoughlin, “Isaac Backus and the Separation of Church and State in America,” American Historical Review 73, no. 5 (June 1968): 1404-05; Isaac Backus, An Appeal to the Public for Religious Liberty, against the Oppressions of the Present Day (Boston, 1773), 19, 52, 54; William McLoughlin, “Massive Civil Disobedience as a Baptist Tactic in 1773,” American Quarterly 21, no. 4 (Winter 1969); 725; Mark Noll, Christians in the American Revolution (Washington, D. C., 1977), 80-87. 16 long speeches in which they argued that “there is indeed an ecclesiastical establishment in our province but a very slender one, hardly to be called an establishment.” The meeting went downhill from there, with Samuel Adams suggesting the outlandish complaints “came from enthuseasts who made a merit of suffering persecution, and also that enemies to these colonies had a hand therein.” The Massachusetts delegates pointed out that Baptists needed only to file certificates of tax exemption for dissenters, but Backus insisted that the often-abused certificates also represented a violation of conscience. The Massachusetts delegates ended the session by offering to bring the grievances to the Massachusetts assembly, but John Adams still cautioned that “we might as well expect a change in the solar systim, as to expect they would give up their establishment.”19 When Lexington and Concord forced a decision in 1775, most New England Baptists joined the cause of independence, hoping the Patriot calls for liberty would eventually bring their own full religious rights. The College of Rhode Island closed for several years during the war, but when it reopened the trustees commissioned the fashioning of a new college seal, minus the bust of King George III. In 1782 Manning still feared for the college’s future, telling Backus the “State of the College is really deplorable,” and that if it did not receive sufficient support they “must wholly relinquish it.”20 Despite the troubles of the Revolutionary period, Manning and Backus later wrote the “American Revolution…doubtless, stands closely connected with many other [events], which will take place in their order, and unite in one glorious end, even the advancement and 19 William McLoughlin, Diary of Isaac Backus 2: 915-17; McLoughlin, Isaac Backus, 129-32; Thomas McKibbens, Jr. and Kenneth Smith, The Life and Works of Morgan Edwards (New York, 1969), 25-40. 20 James Manning to Isaac Backus, Aug. 3, 1782, no. 1562, Papers of Isaac Backus (Ann Arbor, Mich., 2003). 17 completion of the Redeemer’s kingdom.” Worldly men would interpret the Revolution only through the lenses of freedom and liberty, while the godly would take an eschatological view, argued Backus and Manning. The Revolution, they believed, was “design’d by the Lord to advance the cause of Christ in the world; or as one important step towards bringing in the glory of the latter day.” As the “principles of liberty” spread, so also would true religion. “As light or sacred knowledge shall be diffused, Antichrist will be destroyed.” The gospel would spread throughout the whole earth, but they thought it not “at all improbable, that America is reserved in the mind of JEHOVAH, to be the grand theatre on which the divine Redeemer will accomplish glorious things.” They noted with pleasure that some revivals had recently appeared as signs of those “glorious things.” They called on the Baptist churches to pray for “a more universal effusion of the Holy Ghost.” Backus and Manning would have been delighted to know just how quickly the Baptist church would grow in America over the next seven decades. As part of the stunning evangelical Protestant boom during that period, the total number of Baptist churches rose from about 150 in 1770 to just over 12,000 in 1860. However, full disestablishment, and full religious freedom for Baptists, did not come to Massachusetts until 1833.21 The founding of the College of Rhode Island, the Warren Association, and the Baptists’ alignment with the Patriot cause fit almost perfectly Max Weber’s model of how marginal, charismatic religious sects become established, rational denominations. Eventually, after a vigorous political campaign for their religious freedom, the legal harassment and oppressive taxation they faced in earlier years were dropped by the New England state governments. Baptists in New England had become respectable. From then on, Baptists and other marginalized 21 Warren Association, Minutes of the Warren Association ([Boston?, 1784]), 6-7; Mark Noll, America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham Lincoln (New York, 2002), 166. 18 religious groups––including Catholics, Mormons, and fundamentalists of all stripes––used higher education and other means to establish social respectability and denominational stability. In a remarkably frank statement of the Baptists’ intentions, the Warren Association said it was founded for the purpose of “becoming important in the eye of the civil powers.”22 Brown did not lose its intentional Christian identity for another century, thanks largely to the long mid-nineteenth century presidency of Francis Wayland, who remained largely faithful to the Baptist tradition after his predecessor resigned because of his Unitarian beliefs. By the early twentieth century, Brown had clearly become one of the nation’s elite universities, and it enjoyed the benevolence of magnates John D. Rockefeller and Andrew Carnegie. Fearing that it might appear “sectarian” or narrow, however, Brown also began to cut its ties with the Baptist church. For a time, President William Faunce tried to manage the tension by reportedly (in a possibly apocryphal quote) explaining, “When I speak in Baptist churches and their mission boards, Brown is a church-related university. When I speak to the officers of the educational foundations, Brown is a university.” Finally, in 1910, Brown officials announced denominational tests for the Trustees and President would no longer be observed, in order to secure funding from agencies like the Carnegie Foundation, and to “fulfill the real purpose of the founders.” The voyage to cultural respectability was finished.23 22 The Sentiments and Plan of the Warren Association (Germantown, Pa., 1769), 3, quoted in Susan Juster, Disorderly Women: Sexual Politics and Evangelicalism in Revolutionary New England (Ithaca, N. Y., 1994), 113, see also 109. Revealingly, the Association dropped the “becoming important” clause fourteen years later. 23 “Sectarian Brown,” New York Times, June 19, 1910, p. 10; Faunce quote from James T. Burtchaell, The Dying of the Light: The Disengagement of Colleges and Universities from their Christian Churches (Grand Rapids, 1998), 823; Bronson, Brown University, 470-71. On the problems caused by explicit Christian commitments at research 19 The story of the New Light Baptists and College of Rhode Island should give us pause to consider the place of education and respectability in the Baptist tradition, and the broader Christian tradition. It would be hypocritical for me to characterize the founding of the College of Rhode Island as a sell-out, as I currently work for and enjoy the largesse of the largest Baptist university in the world, Baylor University. However, the history of the College of Rhode Island at least suggests Baptists should view the religious function of Christian higher education as susceptible to dilution in the quest for respectability. Baptists need education and educated leaders, just as all Christians do. When it is appropriated in a godly way, education brings humility and wisdom. It mitigates against a kind of “me and Jesus” naiveté about the tradition of the church. It can give a stabilizing depth and richness to the church’s teaching. Educational institutions strengthen and perpetuate the best elements of denominational heritage. They can encourage young adults to appropriate Christian disciplines. Learning can give students a Christian worldview that is both orthodox, and tailored to the maturing individual soul. Baptists should not say (a la Pink Floyd) “we don’t need no education.” But no one is really arguing anymore that Baptists (or Christians) “don’t need no education.” Instead, it seems that the problem may be a lack of critical reflection on the goals and presuppositions of Baptist education. Should one of Baptists’ main goals be respectability? Maybe it should be one of our goals, but the pursuit of respect should be tempered by an expectation of the offense of the gospel, and the sojourning character of a biblical Christian life. universities, see George Marsden, The Soul of the American University: From Protestant Establishment to Established Nonbelief (New York, 1994), 265-70. 20 One of the greatest difficulties facing Baptist educational institutions is that they often exist in areas where the Baptist church relates cozily with cultural establishment. It certainly does not hurt one’s career opportunities in Texas, for instance, to be known as a garden-variety Baptist. Baptist fundamentalists like to think of themselves as opposed to dominant culture, and perhaps on some moral issues they are, especially when compared to “blue state” voters.24 Some Baptist moderates in the South may think that they are really counter-cultural because they are Democrats. But that only means they are countering the fundamentalists and the Religious Right. Neither Democratic nor Republican politics, nor advocating for them in the college classroom, offers a way to be counter-cultural in a biblical sense. It is difficult to maintain a dissenting stance when you have “made it” as part of the establishment. Baptists have been at their best historically when they have really been dissenters. Isaac Backus (at least in his early years) and Martin Luther King, Jr. were model Baptist dissenters. They had clear enemies to fight: religious establishments and Jim Crow-era racism, respectively. But what do Baptists (and Baptist universities) do when they fit comfortably–– maybe a little too comfortably––within the established arrangements? There is no point in inventing ways to dissent. No one is fooled by Baptists or Christians who claim to be countercultural when they are really mainstream. Nevertheless, Baptists in higher education can at least keep a modest critical edge in twenty-first century America by insisting that Christ demands our highest allegiance, and that Christ does not simply add value to our institution. We should be wary of plans that suggest Christian institutions can be “as good as” secular ones, with Jesus added. Instead, we should 24 Barry Hankins, Uneasy in Babylon: Southern Baptist Conservatives and American Culture (Tuscaloosa, Ala., 2002). 21 simultaneously affirm the pluralism of our culture and assert that if Jesus is Lord, he can transform the established culture, partly through his scholarly followers working in their fields and classrooms. If cultural respect can be won without Baptists or Christians masking their conviction that the gospel is truth, then we should seek respect cautiously. It can be a powerful testimony to established powers when a scholar produces world-class research, while remaining openly identified with Christ. In my own field, Christian historians like Nathan Hatch, Mark Noll, and George Marsden are widely recognized as among the most brilliant and prolific, and yet critics still seem to suspect that these scholars have an agenda driven by their faith that should be scrutinized. This seems to me, for our time and place, a good model for the role of the Christian scholar and the Christian university. It risks embarrassment because of open association with Christ, and yet engages with broad, established, published academic discourses. Christian scholars, and schools that employ them, should publicly and intentionally identify with Jesus, but refuse to retreat into a fundamentalist enclave where dominant cultural views or ideas will not intrude. Christian scholars and their host schools should also resolve to maintain a vital relationship with their sponsoring churches. Though church people and officials can be frustrating to professional academics, not least because of persistent anti-intellectualism, Baptist academics should remain vitally involved with the life of their local churches. They should expect their institutions to maintain a warm relationship with Baptist churches through recruiting students, and by requiring most top administrators and trustees to be committed Baptists. Once religious schools decide the founding church, and Christianity generally, is too embarrassing to identify publicly with them, secularization has arrived. The desire for cultural respectability 22 should never lead to a denial of the particularity of one’s Baptist, or especially Christian allegiances.25 Finally, Baptists should be particularly wary of theologies that privatize or individualize Christian faith to the point that it is relativized or made irrelevant. These kind of theologies are particularly attractive in higher education because they make it easy to fit into the broader world of academia. All Christians relate to God individually, but that does not mean that any and every conception of God’s truth is valid. Just as eighteenth-century Baptists did, modern Baptists should both elevate their distinctives and intentionally identify with historic Christianity. One of the best things that education can do for Christians is to show them what is essential and orthodox, and what is non-essential and trendy about their faith. Though we see “through a glass darkly,” Baptists should continue to affirm apostolic Christianity, not “me and Jesus” individualism. Separate critics were wrong to oppose the founding of the College of Rhode Island. The time had come for a Baptist college. However, the leaders of Brown paid a considerable price when they pursued the accolades of men, ultimately, at the cost of a distinctive Christian identity, or any Christian identity at all. Departing from their countercultural roots, the Baptists of New England became so closely identified with the dominant culture that they forgot why an institution like Brown needed to be Baptist, or Christian, any more. 25 Robert Benne, Quality with Soul: How Six Premier Colleges and Universities Keep Faith with Their Religious Traditions (Grand Rapids, Mich., 2001), 63-64.