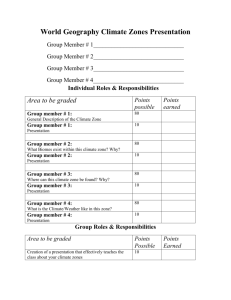

About Zones

advertisement

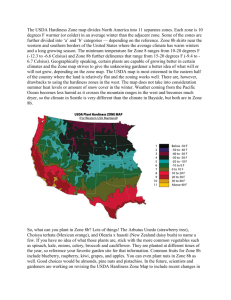

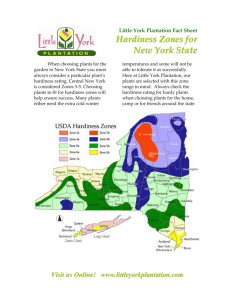

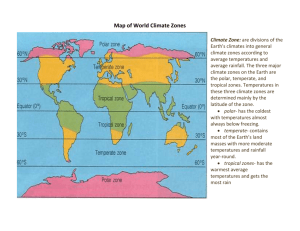

About Zones Sunset Western Climate Zones Sunset's Western Climate Zone system divides the Western U.S. into 24 climate zones. Each takes into account winter cold and summer heat, humidity, elevation and terrain, latitude, and varying degrees of continental and marine influence on local climate. Use the following descriptions to find the Sunset climate zone number that matches conditions where you live so you can choose the right plants for your garden. Cold and Snowy Zones: 1, 2, and 3 Rainy Northwest Zones:4, 5, and 6 Northern and Interior-alley California Zones: 7, 8, 9, 14, 15, 16, and 17 Southern Caliornia Zones: 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24 Southwest Desert Zones: 10, 11, 12, and 13 Find the zone number that corresponds most closely to your area by looking at our zone finder maps. The Cold and Snowy Zones: 1, 2, and 3 Zone 1. Zone 1 includes the coldest areas of the West—all of Wyoming and portions of the states surrounding it: Montana, Idaho, Utah, and Colorado. Zone 1 is also found along the Sierra Nevada range of California and Nevada. This zone has the shortest growing season of any in the West, between 75 and 150 days. And because frosts can occur any night of the year, gardeners in this zone employ a variety of techniques to protect plants from cold and wind. It’s especially important here to choose plants that can withstand the cold. While some marginal plants may live, they’ll be susceptible to disease and pests. Zone 2. Zone 2 differs from Zone 1 primarily in the coldness factor—average winter lows are slightly higher. Zone 2 areas cover much of Colorado and Utah, parts of eastern Oregon and Washington, and western Idaho. The high plateaus of New Mexico and Arizona, and parts of Nevada and the high country in California are also Zone 2 areas. The growing season here is usually 150 days per year (though in some areas it is 200 days). The longer season, along with slightly milder temperatures, makes it possible to grow a few more plants. In many locations, by planting windbreaks and mulching heavily, you can grow plants that would otherwise perish from the effects of wind, cold, and winter sun. Zone 3. This is the mildest of the three snowy-weather zones in the West. It includes the fruit- and crop-growing areas along the eastern Columbia River and portions of Idaho near Boise. This zone also extends along the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada range, encompassing the Reno area, and it includes the Coast Ranges of Oregon and Washington. The growing season here is usually 160 days (although 220 days can be usual around the Walla Walla region of eastern Washington). On the east side of the Cascade Range and the Sierra Nevada, the drying winds of winter exacerbate the cold by dehydrating plants growing in frozen soil. And along the Coast Ranges in Oregon, the heavy winter rain, occasional snow, and rugged terrain combine to limit plant grown. The Rainy Northern Zones: 4, 5, and 6 Zone 4. Many people know this zone for the miles of tulips in the Skagit Valley. In fact, this area has more spring bulbs under cultivation than all of the Netherlands. The slightly colder winters of Zone 4—compared to those of Zones 5 and 6—help induce dormancy in the bulbs. Zone 4 extends into the greater Seattle area. Zone 5. Zone 5 includes the coastline areas of Washington and Oregon that are famous for lush vegetation. While it’s not particularly warm in the summer (it’s hard to grow tomatoes in some areas), the long growing season favors flowering plants, such as fuchsias. Native plants of all types, including salal and Oregon grape (Mahonia aquifolium), thrive in this zone. Zone 6. Zone 6 includes the Willamette Valley and the areas around Portland/Vancouver, and follows the Columbia River a few miles both upriver and downriver from Portland. It’s been said that more plant varieties are grown in the Willamette Valley than in any comparable acreage anywhere in the world. Drive Interstate 5 from Medford to Portland, and you’ll see orchards and farms that are growing fruit trees, berries, hops, vegetables, and many ornamental trees and bushes. Sitting right below the Columbia River Gorge, Portland and its surrounding areas often experience periods of freezing rain and ice storms, which can kill fragile trees and shrubs. The Northern and Interior-Valley California Zones: 7, 8, 9, 14, 15, 16, and 17 Zone 7. Zone 7 is found in Northern California and Oregon’s Rogue River valley. While the summers are mild and ideal for many crops and gardens, the growing season is shorter than in neighboring Zones 8 and 9. The winter is also somewhat colder, making this an excellent climate to grow plants that need some winter chill to thrive, such as peonies and flowering cherries. The region is noted for its pears, apples, peaches, and cherries. Pests that bother fruit trees are a major consideration, and mulching against the cold is often necessary. Zone 8. The center of the Central Valley is Zone 8, noted for its cold-air basins. The crops that thrive here are those needing some winter chill (similar to Zone 7). You’ll drive by miles of orchards that require the cooler winter to set fruit. You’ll also see many heat-loving plants, though mostly those that handle the cooler winters. Zone 9. While cool air flows downward into the valley, where it gets trapped, the surrounding low-elevation foothills are warmer. This is Zone 9. Zone 9 is safest for heatloving plants like citrus, hibiscus, melaleuca, and pittosporum. The weather can be cold in the winter, including long periods with thick tule, or ground, fog. During extremely cold periods, air blowers are needed to keep the temperature from dropping too low and killing the citrus crop. Zone 14. Zone 14 covers the small Napa and Sonoma wine-growing areas of California in its cooler and marine-influenced section, and the rich farmlands of the Sacramento– San Joaquin River delta area in its warmer inland area. (Some similarly zoned areas extend down the coast almost to Santa Maria.) Fruits that need winter chilling do well here, as do shrubs needing summer heat. Zone 15. Like Zone 14, Zone 15 favors plants that need some winter chill to succeed and has warm, sunny summers. Yet because of its proximity to the ocean, its atmosphere is more moist, and it has cooler summers and milder winters. It is found slightly farther from the ocean and from San Francisco Bay than 14, extending up and down the coast from Mendocino to Santa Maria. Like Zones 16 and 17, it has nearly year-round growing conditions. Zone 16. Zone 16 is considered by many to be one of the finest gardening climates in California. It includes thermal belts, which means it gets more heat than areas right next to the coast (Zone 17), but warmer winters than those in Zone 15. It can grow more subtropicals than 15 with less danger of winter frost. It includes areas around the greater San Francisco Bay Area, and portions near the coast south to Santa Maria. Zone 17. Zone 17 is fog country. It’s of this zone that someone (not Mark Twain) said that the coldest winter he ever experienced was a summer in San Francisco. In its cool, moist air, fuchsias, brussels sprouts, and artichokes thrive. There’s rarely any freezing weather in the winter, and summer temperatures mainly stay in the 65–70°F range. In addition to the San Francisco and Monterey bays, this zone extends in a very narrow band up the coast to Crescent City and south to Santa Maria. The Southern California Zones: 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, and 24 Zone 18. Zone 18, located inland from the ocean, was traditionally an area of apricot, peach, apple, and walnut orchards. Now it’s mostly filled with suburban communities. Zone 18 areas are usually found on hilltops and in cold-air basins, where winter lows can range from 28°F to 10°F. While it’s too hot, cold, and dry for fuchsias, you can grow many of the hardier subtropicals here. Zone 19. A warmer version of Zone 18, Zone 19, with winter temperatures that range from 27°F to 22°F, is located next to Zone 18. It is one of the Southern California areas famous for citrus groves. You can grow macadamia nuts and avocados here, as well as many tropical and subtropical plants. Zone 19 is also an inland-valley area, only minimally affected by the ocean. Zones 18 and 19 are viewed as a pair, with the major difference that 18 is cooler. They are both more influenced by inland climate factors than by the ocean. Zone 20. Zone 20, while not on the coast, is influenced by the ocean more than Zones 18 and 19 are. Its winter temperature lows range from 28°F to 23°F. Because of the marine influence, you’ll find you can grow a wider range of plants in this zone than in some neighboring ones. For example, birch, jacaranda, fig, and palm trees all thrive in this zone. Zone 21. Also influenced by the coast, Zone 21 has the mildest winter temperatures of Zones 18 to 22. Winter temperature lows range from 36°F to 23°F, rarely dipping below 30°F. Along with Zone 19, it, too, is a prime citrus-growing area. Like Zones 18 and 19, Zones 20 and 21 are viewed as a pair. Zone 20 is the cooler of the two. In general, they’re both likely to be influenced by the ocean part of the time and by the inland climate at other times. This means that your garden may sometimes feel the effects of the hot Santa Ana winds, and sometimes the cool breezes of the Pacific Ocean. Zone 22. Zone 22 is a special zone that covers Southern California’s coastal canyons. Influenced by marine air, these canyons have somewhat colder winter temperatures deep in their clefts and on their hilltops. While winter temperatures in general are mild along the coast, in Zone 22 canyons you can find average annual winter lows that range from 24°F to 21°F (although they rarely fall below 28°F). If you garden in this area and include subtropical plants, you can protect many from frost damage by planting them under building overhangs or the canopies of trees Zone 23. Zone 23 is one of two coastal zones in Southern California and the one more favored for growing subtropical plants. (Zone 24 is the other coastal zone.) This is the best zone for avocados, and while it isn’t as hot as inland valley zones, it is warm enough to grow warm-weather plants like gardenias. In some winters, the temperatures can drop significantly, with lows ranging from 38°F to 23°F. Along the open hills, warm summer days favor the growing of cacti and warm-weather grasses. Zone 24. If Zone 17 in Northern California represents the typical San Francisco climate, Zone 24 exemplifies San Diego. And while it, too, runs along the coastline, and both are marked by cool marine climate and many foggy days, the San Diego zone is warmer. As in San Francisco, fuchsias thrive here. But you’ll also find many tropicals that grow nowhere else in the western states, including rubber trees (Ficus elastica) and umbrella trees (Schefflera actinophylla), both sold as house plants in most of the West. The Southwest Desert Zones, from California to New Mexico: 10, 11, 12, and 13 Zone 10. Zone 10 is found just below the mountainous regions of Arizona and New Mexico and in southern Utah. It also covers most of eastern New Mexico and parts of southern Nevada. This high-desert zone has a definite winter season; temperatures drop below 32°F from 75 to more than 100 nights each year. With such cold winters, this zone’s gardening season runs from spring through fall; plant in spring. While similar to Zone 11, it receives just a little more rainfall (an average of 12 inches per year, with half falling in July and August) and has a little less wind. Zone 11. Like Zone 10, Zone 11 has cold winters. On the other hand, Zone 11 also is like Zone 13 in having intense summer heat. Gardeners in this zone are among the most challenged in the West. They must contend with hot summer days, cold winter days and nights, late spring frosts, and drying winds. In the Las Vegas area, there are more than 100 days each year when the temperatures are higher than 90°F. Keeping sufficient water on garden plants is especially important—the drying winds and the bright sunlight often combine to dry out even normally hardy evergreen plants, killing or badly injuring them Zone 12. Zones 12 and 13 are similar, the main difference being winter cold. While the average winter low temperatures are comparable, Zone 12 has more cold days. Frosts can be expected some of the time during the four winter months. In Zone 13, frosts usually occur only one month in the winter and not at all in some locations. Zone 12’s desert area is lush, comprising a highly diverse palette of plants, many of which can be included in the home garden. The best season for cool-weather crops, such as salad greens, root vegetables, and cabbage family members, starts in September or October. A typical Zone 12 area is greater Tucson, Arizona. Zone 13. Zone 13 includes the Southwest’s low- or subtropical-desert areas. You’ll find it in diverse locations such as Death Valley, California, and Phoenix, Arizona. Summer temperatures range from 106°F to 109°F, occasionally peaking higher. Here, the gardening year begins in September and October and extends through March and April. Summer rains help established native plantings survive throughout the summer, although most plants will require year-round irrigation. Many gardeners consider the summer months the dormant season, and if they work in their gardens at all, do so shortly after dawn or in the evening twilight. This is the zone famous for grapefruit and date palms. USDA Hardiness Zones The following from: http://www.backyardgardener.com/zone USDA and Canadian Hardiness Zones In an attempt to answer this question, years ago botanists and horticulturists started gathering weather records throughout North America to compile a database to show the average coldest temperatures for each region. These records were condensed into a range of temperatures and transformed into various zones of plant hardiness. Maps were then made to show the lines between these temperature zones. The climactic studies and maps were undertaken by two independent groups: The Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) in Washington, D.C. The two maps reflected some variances, but in recent years, the differences between the Arnold Arboretum and the USDA have narrowed. Today, the USDA map, which was last updated and released in 1990 (based on weather records from 1974-1986), is generally considered the standard measure of plant hardiness throughout much of the United States. Hence we have the USDA Plant Hardiness Zones. So what's wrong with plant hardiness zones? Well, just think about this: The average minimum temperature is not the only factor in figuring out whether a plant will survive in your garden. Soil types, rainfall, daytime temperatures, day length, wind, humidity and heat also play their roles. For example, although both Austin, Texas and Portland, Oregon are in the same zone (8), the local climates are dramatically different. Even within a city, a street, or a spot protected by a warm wall in your own garden, there may be microclimates that affect how plants grow. The zones are a good starting point, but you still need to determine for yourself what will and won't work in your garden. Applying zone references Plant encyclopedias may refer simply, for example, to "Zone 6," which generally means that the plant is hardy to that zone (and will endure winters there), and generally can withstand all the warmer zones below. More detailed information may indicate a range of zones (i.e., "Zones 4-9"), which means the plant will only grow in those zones, and will not tolerate the colder and warmer extremes outside them. But remember, zones are only a guide. You may find microclimates that allow you to grow more than the books say you can; by the same token, you may find to your dismay that some precious plant -- one that's "supposed" to be hardy in your zone -- finds its way to plant heaven instead. Sunset Zones versus USDA Zones Gardeners in the western United States sometimes are confused when confronted with the 11 Hardiness Zones created by the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture), because they are used to a 24-zone climate system created 40 years ago by Sunset Magazine. The Sunset zone maps, which cover 13 Western states, are much more precise than the USDA's, since they factor in not only winter minimum temperatures, but also summer highs, lengths of growing seasons, humidity, and rainfall patterns to provide a more accurate picture of what will grow there. If you live in the western U.S., you'll find that nurseries, garden centers, and other western gardeners usually refer to the Sunset climate zones rather than the USDA plant hardiness zones. In fact, the Sunset zones and maps are what are listed for each plant in Sunset's Western Garden Book and Western Garden CD-ROM, which are considered the standard gardening references in the West. However, the USDA zones are still of importance to western gardeners, since the USDA zones are used in the rest of the country. When you order plants from catalogs or read general garden books, you need to know your USDA zone in order to be able to interpret references correctly. To determine your USDA zone, use the links above. Search Google using “USDA Zones” The USDA Plant Hardiness Zones divide the United States and southern Canada into 11 areas based on a 10 degree Fahrenheit difference in the average annual minimum temperature. Zone refers to your probable lowest temperatures in winter Zone 1 Zone 2 Zone 3 Zone 4 Zone 5 Zone 6 Zone 7 Zone 8 Zone 9 Zone 10 Zone 11 -50°F -50° -40° -30° -20° -10° 0° 10° 20° 30° 40° to to to to to to to to to to -40°F -30°F -20°F -10°F 0°F 10°F 20°F 30°F 40°F 50°F Zone Key Colorado: Zone Fahrenheit Celsius Example Cities 1 Below -50 F Below -45.6 C 2a -50 to -45 F -42.8 to -45.5 C Prudhoe Bay, Alaska; Flin Flon, Manitoba (Canada) 2b -45 to -40 F -40.0 to -42.7 C Unalakleet, Alaska; Pinecreek, Minnesota 3a -40 to -35 F -37.3 to -39.9 C International Falls, Minnesota; St. Michael, Alaska 3b -35 to -30 F -34.5 to -37.2 C Tomahawk, Wisconsin; Sidney, Montana 4a -30 to -25 F -31.7 to -34.4 C Minneapolis/St.Paul, Minnesota; Lewistown, Montana 4b -25 to -20 F -28.9 to -31.6 C Northwood, Iowa; Nebraska 5a -20 to -15 F -26.2 to -28.8 C Des Moines, Iowa; Illinois 5b -15 to -10 F -23.4 to -26.1 C Columbia, Missouri; Mansfield, Pennsylvania 6a -10 to -5 F -20.6 to -23.3 C St. Louis, Missouri; Lebanon, Pennsylvania 6b -5 to 0 F -17.8 to -20.5 C McMinnville, Tennessee; Branson, Missouri 7a 0 to 5 F -15.0 to -17.7 C Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; South Boston, Virginia 7b 5 to 10 F -12.3 to -14.9 C Little Rock, Arkansas; Griffin, Georgia 8a 10 to 15 F -9.5 to -12.2 C Tifton, Georgia; Dallas, Texas 8b 15 to 20 F -6.7 to -9.4 C Austin, Texas; Gainesville, Florida 9a 20 to 25 F -3.9 to -6.6 C Houston, Texas; St. Augustine, Florida 9b 25 to 30 F -1.2 to -3.8 C Brownsville, Texas; Fort Pierce, Florida 10a 30 to 35 F 1.6 to -1.1 C Naples, Florida; Victorville, California 10b 35 to 40 F 4.4 to 1.7 C Miami, Florida; Coral Gables, Florida 11 above 40 F above 4.5 C Honolulu, Hawaii; Mazatlan, Mexico Fairbanks, Alaska; Resolute, Northwest Territories (Canada) The AHS Plant Heat Zone Map by H. Marc Cathey, AHS President Emeritus Most gardeners are familiar with the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Plant Hardiness Zone Map. By using the map to find the zone in which you live, you will be able to determine what plants will "winter over" in your garden and survive for many years. That map was first published in 1960 and updated in 1990. Today nearly all American references books, nursery catalogs, and gardening magazines describe plants using USDA Zones. But as we all know, cold isn't the only factor determining whether our plants will survive and thrive. Particularly during seasons of drought, we are all aware of the impact that heat has on our plants. And although there is still disagreement in the scientific community on this issue, many believe that our planet is becoming hotter because of changes in its atmosphere. The effects of heat damage are more subtle than those of extreme cold, which will kill a plant instantly. Heat damage can first appear in many different parts of the plant: Flower buds may wither, leaves may droop or become more attractive to insects, chlorophyll may disappear so that leaves appear white or brown, or roots may cease growing. Plant death from heat is slow and lingering. The plant may survive in a stunted or chlorotic state for several years. When desiccation reaches a high enough level, the enzymes that control growth are deactivated and the plant dies. USING THE HEAT-ZONE MAP Use the AHS Plant Heat-Zone Map in the same way that you do the Hardiness Map. Start by finding your town or city on the map. The larger versions of the map have county outlines that may help you do this. The 12 zones of the map indicate the average number of days each year that a given region experiences "heat days"-temperatures over 86 degrees (30 degrees Celsius). That is the point at which plants begin suffering physiological damage from heat. The zones range from Zone 1 (less than one heat day) to Zone 12 (more than 210 heat days). Thousands of garden plants have now been coded for heat tolerance, with more to come in the near future. You will see the heat zone designations joining hardiness zone designations in garden centers, references books, and catalogs. On each plant, there will be four numbers. For example, a tulip may be 3-8, 8-1. If you live in USDA Zone 7 and AHS Zone 7, you will know that you can leave tulips outdoors in your garden year-round. An ageratum may be 10-11, 12-1. It can withstand summer heat throughout the United States, but will over winter only in our warmest zones. An English wallflower may be 5-8, 6-1. It is relatively cold hardy, but can't tolerate extreme summer heat. Gardeners categorize plants using such tags as "annual" or "perennial," "temperate" or "tropical," but these tags can obscure rather than illuminate our understanding of exactly how plants sense and use the growthregulating stimuli sent by their environment. Many of the plants that we consider annuals-such as the petunia, coleus, snapdragon, and vinca-are capable of living for years in a frost-free environment. The Heat Map will differ from the Hardiness Map in assigning codes to "annuals," including vegetables and herbs, and ultimately field crops as well. Plants vary in their ability to withstand heat, not only from species to species but even among individual plants of the same species! Unusual seasons-fewer or more hot days than normal-will invariably affect results in your garden. And even more than with the hardiness zones, we expect gardeners to find that many plants will survive outside their designated heat zone. This is because so many other factors complicate a plant's reaction to heat. Most important, the AHS Plant Heat-Zone ratings assume that adequate water is supplied to the roots of the plant at all times. The accuracy of the zone coding can be substantially distorted by a lack of water, even for a brief period in the life of the plant. Although some plants are naturally more drought tolerant than others, horticulture by definition means growing plants in a protected, artificial environment where stresses are different than in nature. No plant can survive becoming completely dessicated. Heat damage is always linked to an insufficient amount of water being available to the plant. Herbaceous plants are 80 to 90 percent water, and woody plants are about 50 percent water. Plant tissues must contain enough water to keep their cells turgid and to sustain the plant's processes of chemical and energy transport. Watering directly at the roots of a plant-through drip irrigation for instance-conserves water that would be lost to evaporation or runoff during overhead watering. In addition, plants take in water more efficiently when it is applied to their roots rather than their leaves. Mulching will also help conserve water. There are other factors that can cause stress to plants and skew the heat-zone rating. Some of them are more controllable than others. Oxygen. Plant cells require oxygen for respiration. Either too much or too little water can cut off the oxygen supply to the roots and lead to a toxic situation. You can control the amount of oxygen your plant roots receive by making sure your plants have good aeration-adequate space between soil particles. Light. Light affects plants in two ways. First, it is essential for photosynthesis-providing the energy to split water molecules, take up and fix carbon dioxide, and synthesize the building blocks for growth and development. Light also creates heat. Light from the entire spectrum can enter a living body, but only rays with shorter wavelengths can exit. The energy absorbed affects the temperature of the plant. Cloud cover, moisture in the air, and the ozone layer-factors we gardeners can't control-affect light and temperature. But you can adjust light by choosing to situate your plant in dappled shade, for instance, if you are in its southernmost recommended heat zone. Daylength. Daylength is a critical factor in regulating vegetative growth, flower initiation and development, and the induction of dormancy. The long days of summer add substantially to the potential for heat to have a profound effect on plant survival. In herbaceous perennials and many woody species, there is a strong interaction between temperature and daylength. This is not a controllable factor in most home gardening situations. Air movement. While a gentle spring breeze can "cool" a plant through transpiration as it does us, fastmoving air on a hot day can have a negative effect, rapidly dehydrating it. Air movement in a garden is affected by natural features such as proximity to bodies of water and the presence of surrounding vegetation, as well as structures such as buildings and roads. You can reduce air circulation by erecting fences and planting hedges. Surrounding structures. If the environment is wooded, transpiration from trees and shrubs will cool the air. On the other hand, structures of brick, stone, glass, concrete, plastic, or wood will emit heat and raise the air temperature. Gardeners wanting plants to produce early or survive in cold zones will often plant them on the south side of a brick wall. Obviously, this would not be a good place for a plant at the southern limit of its heat zone! Soil pH. The ability of plant roots to take up water and nutrients depends on the relative alkalinity or acidity of the soil. Most plants prefer a soil close to neutral (pH 7), but there are many exceptions, such as members of the heath family, which prefer acidic soil. The successful cultivation of any plant requires that it be grown in a medium within a specific pH range. While it is possible to manipulate the pH of soil with amendments, it is easier to choose plants appropriate to your soil type. Nutrients. Plants vary greatly in the ratio and form of elements they need for consistent, healthy growth. When these are present in appropriate quantities, they are recycled over and over again as the residue of woody material and dropped leaves accumulates and decays, creating sustainable landscapes. HOW THE MAP WAS CREATED The data used to create the map were obtained from the archives of the National Climatic Data Center. From these archives, Meteorological Evaluation Services Co., Inc., in Amityville, New York-which was also involved in the creation of the Hardiness Map-compiled and analyzed National Weather Service (NWS) daily high temperatures recorded between 1974 and 1995. Within the contiguous 48 states, only NWS stations that recorded maximum daily temperatures for at least 12 years were included. (Due to the amount of missing data in Alaska and Hawaii, the 12-year requirement was reduced to seven years at several stations.) Because they were too difficult to map, data from weather stations at or near mountain peaks in sparsely populated areas were not incorporated. A total of 7,831 weather stations were processed; 4,745 were used in plotting the map. PURCHASE A COPY OF THE MAP Durable full-color posters of the AHS Heat-Zone Map are available for $9.95 each. To order click here or , call (800) 777-7931 ext. 137. Publications - USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) is in the process of creating another version of the hardiness map using new mapping technology and an extended set of meteorological data. The new version of the revised map will include 15 plant hardiness zones to reflect growing regions for sub-tropical and tropical plants.