Evans Family History: Genealogy in Powys, Wales

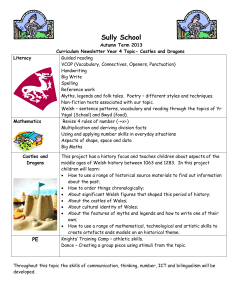

advertisement