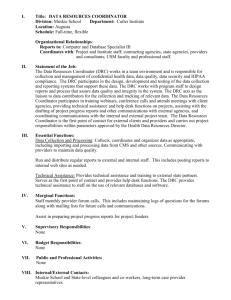

The Continuing War in the Democratic Republic of Congo

advertisement

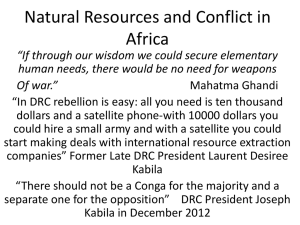

The Continuing War in the Democratic Republic of Congo Background Guide Events of the War The Second Congo War (also known as the Great War of Africa) began in August 1998 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly called Zaire), and officially ended in July 2003 when the Transitional Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo took power; however, hostilities have continued since then. Despite a formal end to the war in July 2003 and an agreement by the former belligerents to create a government of national unity, 1,000 people died daily in 2004 from easily preventable cases of malnutrition and disease. The war and the conflicts were driven by, among other things, the trade in minerals. The deadliest war in modern African history, it directly involved eight African nations, as well as about 25 armed groups. By 2008, the war and its aftermath had killed 5.4 million people, mostly from disease and starvation, making the Second Congo War the deadliest conflict worldwide since World War II. Millions more were displaced from their homes or sought asylum in neighbouring countries. As with most conflicts in Africa, the current situation has much to do with the legacy of colonialism. Since the violent 1885 Belgian imposition of colonial rule by King Leopold II who regarded it as his personal fiefdom and called it the Congo Free State, millions of people have been killed. The murders were grotesque and grossly inhumane. After 75 years of colonial rule, the Belgians left very abruptly, relinquishing the political rights to the people of Congo in 1960. However, economic rights were not there for the country to flourish. As well as Belgium’s historical interests, the changing world after World War II meant Cold War interests also played its part. Just a few months after Lumumba became head of state, he was overthrown with US and European support for a Cold War ally, Mobutu Sese Soko, (and for the rich resources that would then be available cheaply, rather than used for Congo’s own people and development.) The US backed the dictator Mobutu in the overthrow of the previous leader, Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba in 1960. (Lumumba was also non-aligned in geopolitical/cold-war sense, so not seen as being favourable by the US.) Corruption, siphoning off massive personal wealth, a plunge in copper prices, and mounting debt led to enormous economic downturns. Since then, there have been many internal conflicts where all sides have been supported from various neighbouring states including Zimbabwe and Uganda. The conflict was also fuelled by weapons sales and by military training. The weapons came from the former Soviet bloc countries as well as the United States, who have also provided military training. When Congolese President Laurent Kabila came to power in May 1997, toppling Marshall Mobutu, with the aid of Rwanda, Uganda, Angola, Burundi and Eritrea, it was hoped that a revival would be seen in the region. Instead, the situation deteriorated. Kabila, also backed by the US, had been accused by rebels (made up of Congolese soldiers, Congolese Tutsi Banyamulenge, Rwandan, Ugandan and some Burundian government troops) of turning into a dictator, of mismanagement, corruption and supporting various paramilitary groups who oppose his former allies. As the conflict had raged on, rebels controlled about a third of the entire country (the eastern parts). Laurent Kabila had received support from Angolan, Zimbabwean and Namibian troops. Up to the assassination of Laurent Kabila in January 2001, Angola, Zimbabwe, and Namibia supported the Congolese government, while the rebels were backed by the governments of Uganda, Rwanda, and Burundi. Involvement of Surrounding States The reasons for different regions getting involved are all murky. Rwanda, though small, had a number of forces in large areas of the country. This was during the Rwandan genocide when more than 800,000 mainly Tutsi Rwandans were slaughtered. Hutu militia carried out most of the massacres and fled to neighbouring Congo in the eastern region of the DRC after the genocide. From there, they often launched attacks into their home country, prompting a Rwandan invasion. As a result, Rwanda justified its role in the four-year war by saying it wanted to secure its border, while critics accused it of using the attacks as an excuse to deploy 20,000 troops to take control of Congolese diamond mines and other mineral resources. Amnesty International explains that the difference between Uganda and Rwanda, “in its first report [Report of the UN Panel of Experts, April 2001], is that, unlike Rwanda, the Ugandan government does not benefit directly as a government from the resources exploitation in Congo. Only individuals were gaining from it. But the Ugandan government remained silent and took no disciplinary action against those individuals.” The effects and tactics seen from the conflict have been many, according to the same Amnesty report, including: •Shifting alliances as needed to achieve the economic exploitation; •Repeated military operations and violence in areas rich in mineral resources; •Disrupting humanitarian assistance; •Pillage as a strategy of war; •Targeting harvests •Stealing from medical centers •Systematically pillaging food aid •Killing people for resisting extortion; •Corruption and 'taxation' where the taxes are not used for the stated purposes or are extortionate, while exempting elites in various ways; •Public services have predictably collapsed; •Ethnic rivalries have been fueled by economic interests; •Forced labor and displacement; •Sexual exploitation; Peace Agreement of 1999 and Aftermath Despite the Lusaka peace agreement between the Congolese Government and the rebels that was signed in 1999, there was still fighting going on and the peace was fragile. There were various political problems in trying to get a UN peacekeeping force to provide aid, as killings continued to occur. Due to conflicts of interests, there were fears that the UN peacekeeping mission would even be aborted before it got started. The UN deployed a team known as MONUC. It was a small cease-fire monitoring body whose mandate was strengthened in July 2003 to “protect civilians under imminent threat of physical violence.” Amnesty International has noted that “MONUC has been a hostage to its weak mandate and has lacked the necessary equipment, personnel and international political backing.” On January 16, 2001 Laurent Kabila himself was assassinated and his son Joseph Kabila was sworn in as the new President of the DRC. He said that he would further the need for cooperation with the United Nations in deployment of troops, further dialog of national reconciliation and help revive the stalled Lusaka peace agreements. In a dialogue that was supposed to comprise of five parties—two rebel movements, an opposition group, the Rwandan-backed Congolese Rally for Democracy and the government—only the government and one opposition group were included in talks about the sharing of power. The Lusaka agreements were declared dead, though it was said that attempts would be made to continue dialogue. Various other groups had disagreements on a variety of issues, and as the International crisis group concluded (14 May 2002), “the future for the Democratic Republic of Congo remains uncertain.” Nonetheless, at the end of August 2002, a peace agreement had been signed to supposedly end the civil war, though only Jospeh Kabila, president of DRC, and Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda were party to this agreement. However, the United Nations reported in October 2002 that the plunder of gems and minerals continued, with elite networks running a self-financing war economy centered on pillage. The main fighting has been on the eastern side of DRC. It is mostly under foreign control, and over three quarters of the estimated number of killings have taken place there, with approximately 90 per cent of the DRC’s internally displaced population having fled violence from that region. In 2006, Joseph Kabila was elected as president in what was deemed a credible electoral process where around two thirds of voters actually voted, just under 60% of whom voted for Kabila. Around 40% voted for Jean-Pierre Bemba who was more popular along the eastern part of the country. Kabila was voted in on a strong platform of prices to stamp out corruption and promote health, education, housing, employment and infrastructure. However, some four years on the International Crisis Group describes his record as “abysmal” because his presidency is “seeking to impose its power on all branches of the state and maintain parallel networks of decision-making.” In addition, An International Battle Over Resources Due to the immense natural resources in this nation, various foreign powers, as well as internal, have sought to gain an advantage.Laurent Kabila had accused some of his former allies, such as Rwanda and Uganda as having ulterior motives, especially in terms of resources, such as water, diamonds, and other vast, rich resources and minerals. In fact, all sides have been accused of having commercial interests in this war due to the vast resources involved.The DRC’s rich resources provide easy ways to finance the conflict and the rebels had long been successful in setting up financial administrative bodies in their controlled areas, especially with regards to trading with Rwanda and Uganda, while Kabila had also been able to finance his side of the conflict. There are many resources and minerals etc being exploited, including (but not limited to): •Water •Cassiterite •Diamonds •Tin •Coltan •Copper •Timber A number of major human rights groups have charged that some multinational corporations from rich nations have been profiting from the war and have developed “elite networks” of key political, military, and business elites to plunder the Congo’s natural resources. Yet, a number of companies and western governments pressured a United Nations panel to omit details of shady business dealings in a report out in October 2003. As reported by the British newspaper, The Independent: Last October [2002], the panel accused 85 companies of breaching OECD standards through their business activities. Rape, murder, torture and other human rights abuses followed the scramble to exploit Congo’s wealth after war exploded in 1998. Many governments overtly or covertly exerted pressure on the panel and the Security Council to exonerate their companies. In the report, the cases against 48 companies are “resolved” and requiring “no further action”. Other companiesmay not have been directly linked to conflict, but had more indirect ties to the main protagonists. Such companies benefited from the chaotic environment in the DRC. For example, they would obtain concessions or contracts from the DRC on terms that were more favorable than they might receive in countries where there was peace and stability. Death Toll and the Effect on Civilians As with most conflicts, civilians have suffered immensely. The IRC found that since the war started in 1998, Some 5.4 million people have died in this conflict It has been the world’s deadliest conflict since World War II The vast majority have actually died from non-violent causes such as malaria, diarrhea, pneumonia and malnutrition—all typically preventable in normal circumstances, but have come about because of the conflict Although 19% of the population, children account for 47% of the deaths Some 45,000 continue to die each month Although many have returned home as violence has slightly decreased, Refugees International says there are still some 1.5 million internally displaced or refugees Unfortunately, the scale of death and destruction revealed is not new. While mainstream media reporting has been sparse and many are unaware of the sheer enormity of this conflict various organizations have been reporting about this problem since the very beginnings of the conflict. By mid-2001, one of IRC’s earlier surveys estimated that there had already been around 2.5 million deaths since the outbreak of the fighting in August 1998, with the majority dying of malnutrition and disease that has resulted from the war. Effects on the Environment and Wildlife The coltan trade and battle over the other minerals and resources has also affected DRC’s wildlife and environment. National Parks that house endangered gorillas and other animals are often overrun to exploit minerals and resources. Increasing poverty and hunger from the war, as well as more people moving into these areas to exploit the minerals results in hunting more wildlife, such as apes, for bush meat. Does the World Care? Oxfam, mentioned above, criticized the international community in their 2000 report for still ignoring the DRC. When comparing with the response in Kosovo, they pointed out that “[i]n 1999, donor governments gave just $8 per person in the DRC, while providing $207 per person in response to the UN appeal for the former Yugoslavia. While it is clear that both regions have significant needs, there is little commitment to universal entitlement to humanitarian assistance.” (Emphasis added) Slowly though, in some mainstream media, there have been questions of why international efforts are not seen here, especially when compared to that given to Kosovo. An updated Oxfam report, while written back in 2001, also noted the following facts (some numbers may be out of date and have gotten worse, but the sheer scale of these numbers alone are shocking): •More than two million people are internally displaced; of these, over 50 per cent are in eastern DRC. More than one million of the displaced have received absolutely no outside assistance. •It is estimated that up to 2.5 million people in DRC have died since the outbreak of the war, many from preventable diseases. •At least 37 per cent of the population, approximately 18.5 million people, have no access to any kind of formal health care. •16 million people have critical food needs. •There are 2,056 doctors for a population of 50 million; of these, 930 are in Kinshasa. •Infant mortality rates in the east of the country have in places reached 41 per cent per year. •Severe malnutrition rates among children under five have reached 30 per cent in some areas. •National maternal mortality is 1837 per 100,000 live births, one of the worst in the world. Rates as high as 3,000/100,000 live births have been recorded in eastern DRC. •DRC is ranked 152nd on the UNDP Human Development index of 174 countries: a fall of 12 places since 1992. •2.5 million people in Kinshasa live on less than US$1 per day. In some parts of eastern DRC, people are living on US$0.18 per day. •80 per cent of families in rural areas of the two Kivu Provinces have been displaced at least once in the past five years. •There are more than 10,000 child soldiers. Over 15 per cent of newly recruited combatants are children under the age of 18. A substantial number are under the age of 12. •Officially, between 800,000 and 900,000 children have been orphaned by AIDS. •40 per cent of health infrastructure has been destroyed in Masisi, North Kivu. •Only 45 per cent of people have access to safe drinking water. In some rural areas, this is as low as three per cent. •Four out of ten children are not in school. 400,000 displaced children have no access to education. •Of 145,000 km of roads, no more than 2,500km are asphalt.