Chapter 19 - Las Positas College

advertisement

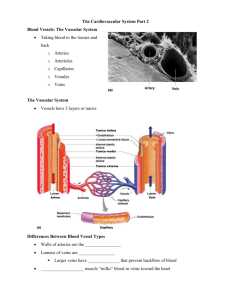

Chapter 19 Blood Vessels PART ONE: GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF BLOOD VESSELS (pp. 556–562) The main types of blood vessels are arteries, capillaries, and veins. Arteries carry blood away from the heart and toward the capillaries; veins carry blood away from the capillaries and toward the heart. Arteries “branch” whereas veins “serve as tributaries.” I. Structure of Blood Vessel Walls (p. 556) A. Except for capillaries, blood vessel walls have three tunics: tunica intima, tunica media, and tunica externa; tunica media is thicker in arteries than in veins. II. Types of Blood Vessels (pp. 556–561, Figs. 19.1–19.6) A. The passage of blood through arteries proceeds from elastic arteries (the largest) to muscular arteries (middlesized, distributing arteries), to arterioles (the smallest). (pp. 556–559, Figs. 19.1–19.2) B. Capillaries are the smallest blood vessels with a diameter of 8–10 µm, just large enough to permit the passage of erythrocytes in single file; the wall is a single layer of endothelium. (pp. 559–561, Figs. 19.1 and 19.3–19.5) 1. A capillary bed is a network of the body’s smallest vessels; beds run through almost all tissues, especially loose connective tissues. (p. 559) 2. Sometimes blood is shunted straight through a capillary bed (from arteriole to metarteriole to thoroughfare channel to venule) and does not enter the true capillaries surrounding the tissue. (p. 559, Fig. 19.4) 3. Capillary permeability permits the exchange of nutrients and wastes between blood and tissue fluid; four routes of capillary permeability allow molecules to pass into and out of capillaries. (p. 560) 4. The blood-brain barrier is an example of low-permeability capillaries; all but the most vital molecules are prevented from leaving the blood and entering the brain tissue. (p. 561, Fig. 19.5a) 5. Sinusoids are wide, leaky capillaries that occur in bone marrow, spleen, and liver tissues. (p. 561, Fig. 19.5c) C. Veins are formed from the smallest veins called venules; the smallest venules are postcapillary venules. (p. 561, Fig. 19.1) D. Venous blood is under less pressure than arterial blood; compared to arteries, veins have thinner walls, a wider lumen, a thinner tunica media, a thicker tunic externa, and valves. (p. 561, Fig. 19.6) E. Vascular anastomoses occur where vessels unite or interconnect; arterial anastomoses serve a common organ, such as the brain or a joint; venous anastomoses are much more common than anastomoses between arteries. (p. 562, Fig. 19.11) F. Vasa vasorum are small arteries, capillaries, and veins that serve walls of larger vessels, such as the aorta. (p. 562, Fig. 19.2) PART TWO: BLOOD VESSELS OF THE BODY (pp. 562–584, Figs. 19.7–19.26) There are several important patterns of circulation; the two basic patterns are pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation; other examples are myocardial circulation, and hepatic portal circulation. I. The Pulmonary Circulation (p. 563, Fig. 19.7) A. Oxygen-poor blood leaves the heart and oxygen-rich blood returns to the heart via the following vessels: pulmonary trunk, pulmonary arteries, lobar arteries, lung capillaries, and pulmonary veins. II. The Systemic Circulation (pp. 563–584, Figs. 19.8–19.26) A. Not all vessels on the right and left sides of the body are mirror images. (pp. 563–564) B. Systemic arteries carry oxygenated blood from the heart to the capillaries of organs throughout the body. (p. 565 and Figs. 19.8 and 19.17) C. The aorta is the largest artery in the body; three parts of the aorta are the ascending aorta, the aortic arch, and the descending aorta. (pp. 565–566, Figs. 19.8–19.9) D. Arteries that supply the head and neck are the single brachiocephalic and paired common carotids, internal and external carotids, and vertebrals; the neck is also supplied by the thryocervical and costocervical trunks. (pp. 566–568, Fig. 19.10) E. The upper limbs are supplied by arteries that arise from the subclavian arteries: axillary, brachial, radial, ulnar, and palmar arch. (pp. 568–569, Fig. 19.11) F. Thorax arteries that supply the thoracic wall are the internal thoracic and intercostal arteries; thoracic visceral organs are supplied by branches of the thoracic aorta. (p. 569, Fig. 19.11) G. Arterial supply to the abdomen arises from the abdominal aorta; abdominal arteries include the inferior phrenics, the unpaired celiac trunk that branches into the left gastric, splenic, and common hepatic, the unpaired superior mesenteric, suprarenals, renals, gonadals, the unpaired inferior mesenteric, lumbars, median sacral, and the common iliac arteries. (pp. 569–571, Figs. 19.12–19.14) H. The following arteries supply the pelvis and lower limbs: common iliac, internal iliac, femoral popliteal, anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and plantar arch. (pp. 571–574, Figs. 19.15–19.16) I. Systemic veins carry de-oxygenated blood from the capillaries of organs throughout the body toward the heart; the superior and inferior venae cavae are the body’s main veins. (p. 575, Fig. 19.18) J. The superior vena cava receives venous blood from all body regions superior to the diaphragm excluding the heart wall; the inferior vena cava receives venous blood from all body regions inferior to the diaphragm. (p. 577, Figs. 19.18–19.19) K. Most blood draining from the head and neck enter three pairs of veins: the internal jugulars, the external jugulars, and the vertebrals; the dural sinuses drain the brain and empty into the internal jugulars. (pp. 577–578, Fig. 19.20) L. Veins of the upper limb are deep or superficial; deep veins have companion names and locations of the upper limb arteries; superficial veins of the upper limb are the cephalic, median cubital, and basilic. (pp. 578–580, Figs. 19.21–19.22) M. Veins of the thorax are the azygos, the hemiazygos, and the accessory hemiazygos. (p. 580, Fig. 19.21b) N. Most veins of the abdomen share companion names of the abdominal arteries and drain into the inferior vena cava: lumbar, gonadal, renal, suprarenal, and hepatic veins. (p. 581, Fig. 19.23) O. The hepatic portal system delivers nutrient-laden blood from the intestines to the liver; tributaries of the hepatic portal system are the superior mesenteric, splenic, inferior mesenteric, and portal vein. (pp. 581–583, Figs. 19.24–19.25) P. Deep veins of the pelvis and lower limb share the names of the arteries they accompany: plantar arch, posterior and anterior tibials, fibular, popliteal, femoral, external iliac, internal iliac, and common iliac veins; superficial veins are the great saphenous and small saphenous veins. (pp. 582–584, Figs. 19.25–19.26) Q. Portal-systemic anastomoses provide emergency pathways through which back-up portal blood can return to the heart; overloads result in esophageal bleeding, hemorrhoids, and caput medusae. (p. 584) III. Disorders of the Blood Vessels (pp. 585–588) A. Examples of blood vessel disorders are atherosclerosis, aneurysm, deep vein thrombosis of the lower limbs, venous disease, microangiopathy of diabetes, and arteriovenous malformation. IV. Blood Vessels Throughout Life (pp. 588–590, Fig. 19.28) A. Embryonic blood vessels form during week 3. (p. 588) B. All major fetal circulation vessels are in place by the third month. (p. 588) C. Unique fetal anatomical vessels and structures are the umbilical arteries, the single umbilical vein, ductus venosus, foramen ovale, and the ductus arteriosus. (pp. 588–590, Fig. 19.28) Chapter 19: Blood Vessels To the Student The main blood vessels are the arteries, veins, and capillaries. They are dynamic structures that accomplish the delivery of blood throughout your body. There are two basic circuits that comprise the vascular system: pulmonary circulation and systemic circulation. The pulmonary circuit carries blood to the lungs for gas exchange, oxygen is picked up, and carbon dioxide is removed. The systemic circuit delivers oxygenated blood to the tissues of the body in exchange for carbon dioxide. As you study the vascular system, keep in mind many of the arteries and veins are named the same and run side by side. Arteries always carry blood away from the heart, and veins always carry blood toward the heart. Regardless of type, vessels carrying oxygen-rich blood are colored red, and vessels carrying oxygen-poor blood are colored blue. First, learn the general characteristics of blood vessels. Second, practice numerous blood-tracing problems to truly understand the “circuit” of blood circulation. Step 1: Describe the general characteristics of blood vessels. - Name the main types of vessels, describing the directional flow of blood within each type. - Describe the structure and function of three types of arteries and name a body location for each. - Clearly distinguish between capillaries and sinusoids, naming body locations for each. - Explain the structural basis of capillary permeability. - Describe four routes involved in capillary permeability. - Define shunt. - Distinguish between a metarteriole and thoroughfare channel. - Define precapillary sphincter and describe its function. - Compare postcapillary venules to capillaries. - Name the tunics of a blood vessel. - Explain how to histologically distinguish a vein from an artery, including comments on lumina and tunics. - Explain the function of valves in veins, and describe them on varicose veins. - Define vascular anastomoses, explain their functions, and identify body locations. - Define vasa vasorum, explain their functions, and name a couple of their locations. Step 2: Review the heart and the great vessels. - Identify the major vessels associated with the heart. - Review how blood moves through the heart. Step 3: Describe pulmonary circulation. - Name the major vessels of the pulmonary circuit. - Trace a drop of blood in the pulmonary trunk back to the left atrium. - Explain why pulmonary arteries are colored blue and pulmonary veins are colored red in Figure 19.7 in your textbook. Step 4: Describe systemic circulation. - List the major arteries that branch off directly from the aorta and name the part of the body they supply. - List the major veins that serve as tributaries for the superior and inferior venae cavae, naming the parts of the body that they drain. - Describe the special function of the hepatic portal system, and explain the significance of the portal-systemic anastomoses. - Diagram the pathway of the hepatic portal system using a flowchart format. - Name each part of the body drained by a vessel of the hepatic portal system. - Explain what makes a portal system extremely unique and answer the question, “Does the human body have other portal systems, and if so where?” - Trace a drop of blood from the kidney to the spleen. - Trace a drop of blood from the descending colon to the right hand. - Formulate several blood-tracing problems and check your answers with your professor. Step 5: Describe blood vessel disorders. - Distinguish atherosclerosis from arteriosclerosis (see A Closer Look). - Describe deep vein thrombosis of the lower limb. - Describe venous disease and the population it affects most. - Describe microangiopathy of diabetes. - Describe the various arteriovenous malformations. Step 6: Describe fetal circulation. - Define placenta. - Name fetal vessels that carry blood to and from the placenta and describe the concentration of oxygen contained in them. - Define shunt. - Explain how the ductus venosus, ductus arteriosus, and foramen ovale function as fetal circulatory shunts. - Describe what happens to the ductus arteriosus and foramen ovale at birth. - Identify the adult structures derived from the ductus venosus, ductus arteriosus, foramen ovale, umbilical arteries, and umbilical vein. - Trace a drop of fetal blood from the placenta back to the placenta, including shunts. Indicate regions of oxygen concentration (high, moderate, low, and very low) along the pathway.