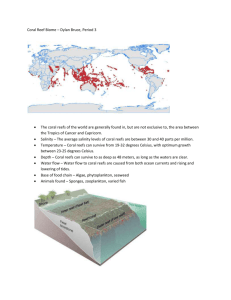

Status and trends of coral bleaching

advertisement